All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in March 2025.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in March 2025.

S. Croce in Gerusalemme

S. Croce in GerusalemmeLinks to this page can be found in Book 3, Map A4, Day 1, View B9 and Rione Monti.

The page covers:

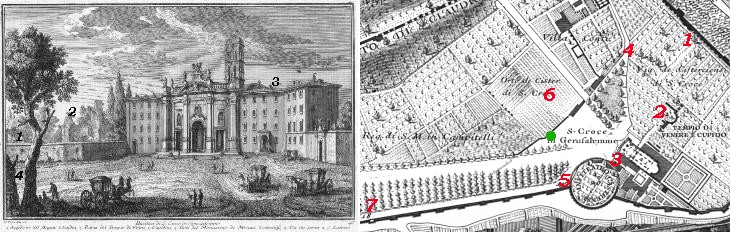

The plate by Giuseppe Vasi

Today's view

S. Croce in Gerusalemme

Tempio di Venere e Cupido, Circus Varianus and Houses of Imperial Officers

Terme Eleniane

S. Maria del Buon Aiuto and Oratorio di S. Margherita

The lonely situation of this antique Basilica, amidst groves, gardens and vineyards, and the number of mouldering monuments and tottering arches that surround it, give it a solemn and affecting appearance.

John Chetwode Eustace - A Classical Tour through Italy in 1802

S. Croce in Gerusalemme is one of the Sette Chiese, the seven Roman basilicas which are visited by pilgrims, especially during the Jubilee years. It is said to have been built

by St. Helena to house the fragments of the True Cross she found in Jerusalem and brought to Rome. At the time of the plate

the fašade had just been redesigned (1743) by Domenico Gregorini and Pietro

Passalacqua at the initiative of Pope Benedict XIV.

The view is taken from the green dot in the small 1748 map below.

In the description below the plate Vasi made reference to: 1) Acquedotto dell'Acqua Claudia; 2) Tempio di Venere e Cupido;

3) Monastery; 4) Street leading to Porta S. Lorenzo. 1) is covered in another page. The small map shows also 5) S. Maria del Buon Aiuto; 6) Terme Eleniane; 7) Oratorio di S. Margherita.

The view in May 2009 (you may wish to see a 1909 watercolour by Yoshio Markino depicting the basilica)

The basilica is no longer in a remote area of Rome, but a large space in front of it has been preserved from modern buildings and the view is almost

that shown in Vasi's etching. It faces north-west and therefore it is best seen in the afternoon of a day near the summer solstice.

You may wish to see the basilica as it appeared in a 1588 Guide to Rome, when it was surrounded by walls and its aspect was very similar to that of S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura.

(left) Fašade (of the vestibule); (right) bell tower (XIIth century)

We may now follow the lines of white mulberry-trees across the open space in front of St. John Lateran to Sta. Croce. The sister basilicas look at each other, and at Sta. Maria Maggiore, down avenues of trees. On the left are the walls of Rome. (..) But the exterior of the church is disappointing and inappropriate, retaining nothing antique except the square Lombardic tower of the twelfth century, in storeys of narrow-arched windows, its brickwork ornamented with disks of coloured marble, and a canopy, with columns, near the summit, for a statue no longer in its place. Augustus J. C. Hare - Walks in Rome - 1873

The original church was made up of the large hall with an apse of an ancient Roman residence. It was modified in the XIIth century by the addition of a transept and the division of the hall into three naves.

Other major changes were made in 1743 when an elliptical vestibule, perhaps the swansong of Roman baroque architecture, was added before the church.

Apse and rear part of the church which shows the walls of Helena's palace

The Palace, inside the walls, is known in documents of a later age as the Palatium Sessorianum. The origin of the name is obscure, but the fact that it was an Imperial residence of the third and part of the fourth century is undoubted. Helena, mother of Constantine, preferred it to the Palace of the Caesars, and the place is full of associations of her. (..) I confine myself strictly to archaeological evidence: but Church documents give fuller details about their works, and about the transformation of the great hall of the palace into a Christian place of worship under the title of Hierusalem. This hall resembled very closely in shape and dimensions the Templum Sacrae Urbis turned into a church by Felix IV. Constantine left the hall as it was; he only closed the lower arches opening on the garden, and added an apse at the east end.

Rodolfo Lanciani - The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome - 1897

Museum of the Basilica: XIIth century frescoes portraying two Patriarchs

In 1913 during a restoration of the building some detached frescoes of the old church were discovered in a recess under the roof where most likely they had been forgotten at the end of a late XVth century redecoration of the apse.

(left) St. Helena (the same image is shown in the background of this page); (centre) angels worshipping the Cross; (right) Emperor Constantine

The churches and palaces of these days are crowded with pretty ornaments, which distract the eye, and by breaking the design into a variety of little parts, destroy the effect of the whole. Every door and window has its separate ornaments, its moulding, frize, cornice, and tympanum; then there is such an assemblage of useless festoons, pillars, pilasters, with their architraves, entablatures, and I know not what, that nothing great or uniform remains to fill the view.

Tobias Smollett - Travels through France and Italy - 1766

The fašade is crowned by gigantic statues. One of them portrays Emperor Constantine, the son of St. Helena, as if he were a saint (for the Greek Orthodox Church he is a saint). You may wish to see a gigantic statue of Constantine by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and one of St. Helena by Andrea Bolgi, one of his assistants.

Vestibule: inner portal (see similar heads of angels by Francesco Borromini at S. Giovanni in Laterano)

Benedict XIV., in 1744, put the

whole church in repair, rebuilt its portico and front,

and opened a new access to it from the basilic

of S. John Lateran, having

employed, on the occasion, Domenico Gregorini, whom

Milizia (Francesco Milizia, a neoclassic art historian) numbers among the very inferior architects

of Rome, a character fully sustained by the changes

made by him in the church before us. (..) The portico, which is elliptical, is externally and

internally as capricious as if the genius of Borromini had presided over its destinies. In its interior

are disposed six columns two of grey granite, two

of red granite, and two of a rare lumachella (a shell-based marble).

Rev. Jeremiah Donovan - Rome Ancient and Modern - 1843

(left) Dome of the vestibule: its neat stucco decoration recalls patterns established by Borromini at Cappella dei Re Magi; (right) detail of an oil painting by Corrado Giaquinto on the ceiling of the main nave

The ceiling of the nave is adorned with a

fresco representing the Triumph of the Cross, by

Corrado Giaquinto , a ready, inaccurate and mannered painter, according to Lanzi (Luigi Antonio Lanzi, another neoclassic art historian). Donovan

Giaquinto portrayed Constantine on his knees while his mother introduces him to the Virgin Mary who in turn intercedes on his behalf with the Holy Trinity.

The Emperor did have a need for good advocates as he had ordered the killing of Crispus, his eldest son and Fausta his second wife. The purpose of the painting was to recognize the contribution of Catholic monarchs (and in particular of the Habsburg Roman Holy Emperors) in the stamping out of heresies.

The painting by Giaquinto does not have the illusionistic features of many other Roman ceilings of that period. You may wish to see the ceilings he painted at S. Nicola dei Lorenesi and at S. Giovanni Calibita.

The interior of the church is divided into a nave and two aisles, by massive pillars support the four central of which, being the largest, are decorated with eight massive columns of granite. (..) From the nave and aisles three steps lead up to the transept.(..) The great altar stands isolated on an urn of ferruginous basalt, in which repose the remains of SS. Caesareus and Anastasius; and over it rises a light canopy, sustained by four columns, two of breccia corallina, and two of porta santa (both reddish marbles). Donovan

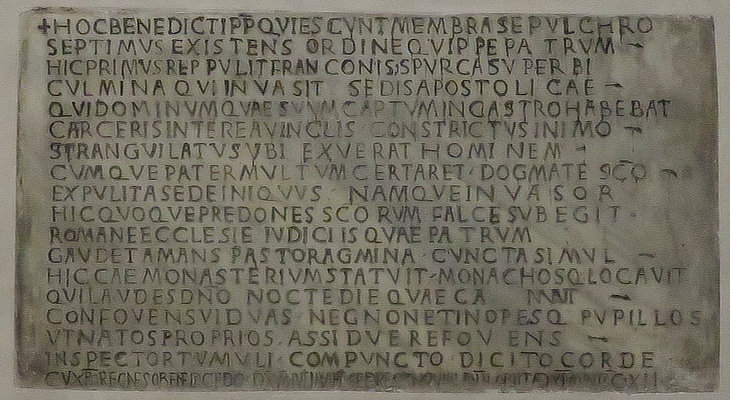

Funerary inscription of Pope Benedict VII with references to Benedict VI and Antipope Boniface VII

The annexed monastery was built by Benedict VII. in 975,

as is attested by his epitaph, affixed to the wall, between the door leading from the church into the monastery and that by which we descend into the chapel of S. Helen.

Donovan

Near the entrance of the church is a valuable monument of the papal history of the tenth century, in a metrical epitaph to Benedict VII., recording his foundation of the adjoining monastery for monks, who were to sing day and night the praises of the Deity; his charities to the poor; and the deeds of the anti-pope Franco, called by Baronius (with play upon his assumed name Boniface) Malefacius, who usurped the Holy See, imprisoned and strangled the lawful pope, Benedict VI., and pillaged the treasury of St. Peter's, but in one month was turned out and excommunicated. Hare

The basilica of S. Croce in Gerusalemme contains but one tomb, that of Benedict VII., whose career is described in a metric inscription of seventeen verses, inserted in the wall of the nave on the right of the entrance. (..) It recalls to our mind one of the most turbulent and riotous periods in the annals of Rome and the papacy, the fight between the "independents" led by the Crescenzi, and the party of the Saxon emperors, represented by Popes Benedict VI. and VII. The Crescenzio mentioned in the epitaph of Benedict VII. was the son of John and Theodora, and one of the most active members of a family which has thrice attempted to reestablish the republic of ancient Rome and shake off the yoke of the German emperors. In 974 Crescenzio committed a sacrilegious murder, that of Benedict VI. Helped by a deacon named Franco he confined him in the dungeon of Castel S. Angelo, while Franco placed himself on the chair of S. Peter, under the name of Boniface VII. The legal Pope was soon after strangled. Such crimes startled for a moment the apathy of the Romans, who besieged and stormed the castle, deposed the usurper, and named in his place Benedict VII., whose grave we are now visiting in S. Croce in Gerusalemme.

Rodolfo Lanciani - Pagan and Christian Rome - 1892

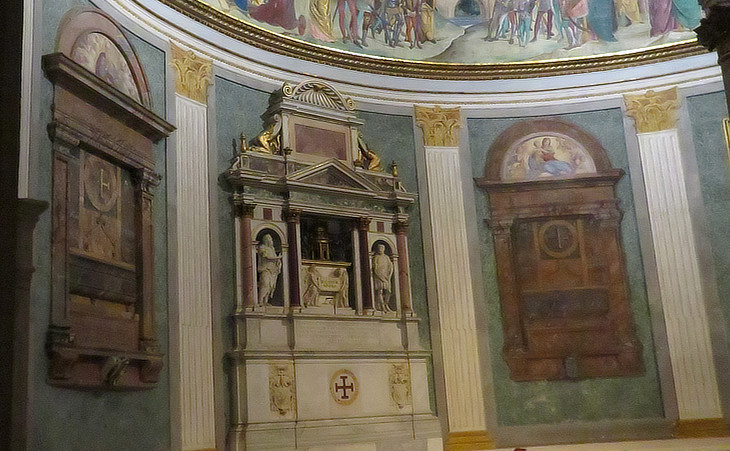

Baroque canopy and apse with late XVth century frescoes depicting events associated with the True Cross (you may wish to see the frescoes by Piero della Francesca at Arezzo depicting the same subject)

The beautiful fresco, on the ceiling of the tribune, representing the discovery of the Cross by S. Helen, and a portion of

it restored to Jerusalem by the Emperor Heraclius,

was executed by order of Card. Carvajal, and is ascribed to Pinturicchio. Donovan

Gregorini and Passalacqua had to work on a tight budget and they did not touch parts of the building. They used the existing ancient columns of a medieval ciborium to

place a very baroque bronze structure above them. The frescoes of the apse were much retouched through the centuries and today are attributed to Antoniazzo Romano.

Funerary monuments in the apse: (left) Cardinal Bernardino Lopez de Carvajal (d. 1523 - the painted frame is a late XVIIth century work); (centre) Cardinal Francisco Quinones (d. 1540); (right) painted empty monument

In the tribune is the tomb of Card. Carvajal, who,

in the XVI. century, repaired the mosaics, which

we shall see in the chapel of S Helen; and the tabernacle in the centre was erected by Card. Quignon,

as is recorded by the inscription. The Cardinal was buried here in 1510. Donovan

Cardinal de Carvajal was the ambassador of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castille to the Holy See. In 1511 he promoted a rebellion against Pope Julius II and he was deposed as a cardinal. In 1517 he was pardoned by Pope Leo X with the penance of one day of fast per month.

Cardinal Quinones was another Spanish cardinal and he commissioned his funerary monument to Jacopo Sansovino when he was still alive (see a fine statue by Sansovino at S. Agostino). Its upper part was designed by Carlo Maderno in the early XVIIth century.

Altars for pilgrims to pray in their visit to the Seven Churches (see those at S. Pietro): (left) Pope St. Sylvester shows the images of Sts. Peter and Paul to Constantine; (right) Vision of St. Robert's mother (ca 1670)

We begin our

round of the church (..) the next altar is that of S.

Sylvester, whose portrait, in the act of showing Constantine the apparition of SS. Peter and Paul, is by

L. Garzi. (..) The next altar-piece is a painting, by

Vanni, of S. Robert, when an infant, being presented to the B. Virgin. Donovan

Depictions of Pope St. Sylvester and Constantine were very popular (see those at SS. Quattro Coronati and in the Tribune of the Lateran), less so of the dream that the mother of St. Robert of Molesme, the future founder of the Cistercians (1075), had during her pregnancy, in which she had a vision of the mystical marriage of her child with the Virgin Mary.

Cappella di S. Elena: (left) mosaic of the ceiling; (right) ancient statue of Juno found at Ostia and turned into a statue of St. Helena in the XVIIIth century

Females are not allowed to enter the chapel

of S. Helen, except on the 20th of March, the anniversary of its Consecration, as is seen by an inscription

to the left of the entrance. This chapel stands on

the spot, covered with a quantity of sacred mould,

sent by S. Helen from mount Calvary, as is recorded

by an inscription on the centre of the floor. It contains three altars, the central one of which is sacred

to S. Helen, whose statue, holding the Cross, is formed from an ancient one. (..) The mosaics, on the

ceiling, of our Lord and the four Evangelists, were

executed in the time of Valentinian III., and repaired

in the XVI. century by Balthasar Peruzzi. Donovan

The main altar and the apse were not the heart of the church. Pilgrims went to S. Croce in Gerusalemme to see the fragments of the True Cross and other relics and these were kept in an underground chapel which is said to have been built by

Empress Galla Placidia (or by her son Valentinian III); it was decorated with (lost) mosaics similar to those of her mausoleum at Ravenna. The decoration of the chapel was renewed in the late XVth century with mosaics perhaps based on drawings by Melozzo da Forlý. In the XVIIth century some fragments of the cross were moved to S. Pietro.

(left) Cappella di S. Elena: coat of arms of Pope Clement VIII and fresco depicting the search for the Cross between allegorical symbols; (right) Cappella Gregoriana: PietÓ

The frescos beneath them, of S. Helen searching for the Cross, testing the true one; venerating it; and dividing it for distribution, are by Pomarancio. (..) The door to the left of the tribune leads down to the subterranean church, in which are two chapels. That to the left, as we enter, is dedicated to the Passion; and its altar-piece of marble represents a Pieta, as the image of the B. Virgin, holding on her knees the lifeless body of her Divine Son, whether in painting or in sculpture, is uniformly called. Donovan

(left) Cappella Gregoriana, a chapel adjoining Cappella di S. Elena: pedestal of a statue of St. Helena (it was found at the time of Pope Sixtus V and based on the text of the inscription it is dated 326); (centre) 1755 monument to Cardinal Gioacchino Besozzi by Innocenzo Spinazzi (see a page on similar monuments); (right) entrance to Cappella delle Reliquie

On the

left side of the entrance to the chapel of S. Helen is a

pedestal (..) This pedestal was found in the adjoining vineyard,

and was erected to S. Helen before Constans was named Caesar, for, whilst the inscription mentions

his two brothers under that title, his name is omitted.

Constans was declared Caesar by his Father in 333,

and S. Helen died in 326: the dedication, which was

made, in her life-time, cannot therefore be posterior

to 326, nor anterior to 323, the year in which Constantius was declared Caesar and hence the inscription probably appertains to 326, when, after the death of Crispus, Constantine left Rome, and Helen, deeply afflicted at the murder of her grandson, set out on her pious pilgrimage to the Holy

Land. (..) Opposite the right aisle is a balcony, from which the sacred relics are exposed to the

veneration of the Faithful and to the rere of the

balcony is the chapel, in which the relics are kept. They consist principally of three portions of the sacred wood of the Cross, now preserved in a silver case of the Title of the Cross; one of the Nails and two of the Thorns. Donovan

The holiness of the underground chapels was increased by the fact that according to tradition their original floors were covered with earth from Jerusalem that

St. Helena had carried with her. Many cardinals, bishops and other pious men chose to be buried in these chapels. Unfortunately for them the relics were moved in 1930 to Cappella delle Reliquie, a new modern chapel which was completed in 1952.

It can accommodate the visit of large groups, but it lacks the appeal which praying where others have prayed for centuries gives to a holy site.

(left) Gate decorated by Jannis Kounellis in 2007; (right) Cistercian garden (redesigned in 2004)

In 1050, the monastery was given by

Leo IX. to Richerio, abbot of Monte Casino: Alexander II. transferred it about 1062 to Canons Regular of S. Frediano of Lucca, in whose hands it remained for 270 years, when it passed to the Cistercians, who held it until 1560, and who were

transferred to the baths of Dioclesian and to them

succeeded its present occupants, who are Cistercians

of the Congregation of Lombardy, brought hither

from S. Sabba. Donovan

The monastery adjoining the basilica belongs to the Cistercian Order, a branch of the Benedictines with a great deal of emphasis on self-sufficiency and manual work; the monks have their kitchen garden inside nearby Anfiteatro Castrense, a Roman small amphitheatre behind the basilica.

The monastery seen from the garden

(left) Tempio di Venere e Cupido; (centre) Musei Vaticani: the statue which was found in the "temple" and after which it is named; (right) Centrale Montemartini: statue of a muse leaning on a rock pillar which was found in 1928 in a new development to the east of the "temple"

The extreme southeast corner of the city, between the line of the Claudian aqueduct and the Amphitheatrum Castrense, seems to have been the property of the Varian family from an early period, and to have been transformed into a park by Sextus Varius Marcellus, father of the Emperor Heliogabalus. Lanciani

The ruins which Vasi attributes to a temple to Venus and Cupid are actually those of a villa built by Emperor Heliogabalus, which later on became part of the residence of St. Helena (Palatium Sessorianum).

The statue of Venus (known as Venus Felix) is said to portray Sallustia Orbiana, wife of Emperor Alexander Severus.

It was found before 1509 when chronicles say that Pope Julius II moved it to Casino di Belvedere.

Remaining evidence of Circus Varianus and the walls of Rome in the background; the modern building to the left of the circus houses Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali

Heliogabalus enlarged and improved the gardens, which became part of the Imperial domain. Here he retired to conspire against the life of his cousin, Severus Alexander, and here he was found, starting a chariot race, by the praetorians eager to take a revenge for the attempted assassination of the cherished young prince. The gardens were cut in two by Aurelian's walls. We do not know whether the part extra muros was abandoned. (..) When Antonio da Sangallo the younger examined the ruins of the circus in the second quarter of the sixteenth century, an obelisk was still lying broken in three pieces in the vineyard of a Messer Jeronimo Milanese. (..) The remains of the Circus were very conspicuous in those days. (..) The obelisk was dug out in 1570 (..) and it was removed in the following century to the Barberini garden. Valadier and Pius VII. erected it at last in the central avenue of the passeggiata del Pincio. It is a work of Hadrian's time, cut in memory of his favorite Antinous. Lanciani

Evidence of two Roman houses and the aqueduct and city walls behind them

The section intra muros continued to be an Imperial garden and residence, and attained great notoriety at the time of Helena and Constantine. Lanciani

When the Aurelian walls were built strips of clear ground immediately adjacent the walls were created. The external strip gave defenders a clear view of what was happening outside and an unobstructed field of shot. The internal strip gave ready access to the rear of the curtain wall to facilitate movement of the garrison to a point of need. The buildings of the imperial residence which adjoined the walls along Aqua Claudia however were not demolished. In 330 Constantine moved the capital of the Empire to Constantinopolis and his successors never resided in Rome, thus the palace was gradually abandoned. In the early Vth century when the walls were repaired / strengthened by Emperors Arcadius and Honorius the buildings along the walls were pulled down and were covered by their own debris. In the late XIXth century the area was a vineyard (Vigna Conti, near 4 in the small map).

Floor mosaics of "Casa dei Ritratti" (House of the Portraits)

In 1959 evidence of the floors of two Roman houses was identified at the foot of the aqueduct/city walls, but only in 2016 a thorough restoration of them was carried out. They testify to the excellence of the technique used by the Romans to make floor mosaics. One of the houses is named after portraits of a man and of a woman at the centre of floor mosaics of two adjoining small halls which are decorated with leaf scrolls and birds.

Floor mosaics: (above) Casa dei Ritratti; (below) Casa delle Fontane (House of the Fountains) see a similar floor having an optical effect at Tomba Barberini

House of the Fountains was named after some small waterproof basins for collecting water in opus signinum, a technique which was used also for floors, e.g. at Solunto and Paestum.

The houses most likely belonged to high officers of the imperial court and are dated early IIIrd century AD, but there is evidence that they were maintained until the mid of the IVth century. Their design and size is almost identical.

House of Aufidia Cornelia Valentilla: floor mosaic of the largest room

Excavations made in 1887 for the opening of Viale Principessa Margherita (today Via Giovanni Giolitti) near the arches of Porta Maggiore led to finding a fistula (lead water conduit) which bore the name of Aufidia. In 1888 three other fistulae were found and Rodolfo Lanciani marked the area as AUFIDIAE VALENTILLAE. DOMUS? HORTI? in his 1893 Forma Urbis Romae.

In 1982 maintenance works under a modern power station in that area led to discovering four rooms of a finely decorated house of the second half of the IInd century AD.

House of Aufidia Cornelia Valentilla: painted walls of the largest room

The paintings follow typical Roman patterns with fake architectures framing large sections of the walls with a single subject at the centre of a wide space. The colours are chiefly red, yellow and white. You may wish to see Insula delle Ierodule at Ostia or House of the Red Walls at Pompeii for other similar paintings.

House of Aufidia Cornelia Valentilla: corridor and the stairs leading to the upper floor

The rooms were slightly below the level of the ground which explains why they were not entirely destroyed when the area near the walls was cleared. There are still three marble steps at the end of a painted corridor which has a particular kind of floor mosaic made up of grey and yellow marble pieces (see a similar floor mosaic at Villa dei Quintili). In the early IVth century, similar to the houses along the aqueduct, the house of Aufidia was inhabited by an imperial officer.

(left) Cistern of Terme Eleniane; (right) Centrale Montemartini: fragment of a floor mosaic depicting a wrestler, similar to those found at Terme di Caracalla

These baths were built at the time of Emperor Septimius Severus between S. Croce in Gerusalemme and an aqueduct built by Emperor Nero which provided them with water. They stood on low ground to be protected from northern winds and they had gardens on their southern side. An inscription found in the XVIth century indicates that they were restored by St. Helena, but it is not clear whether they were public or private baths. Today only the cisterns are visible in a sort of below ground garden surrounded by apartment blocks.

(left) S. Maria del Buon Aiuto; (centre/right) Oratorio di S. Margherita

S. Maria del Buon Aiuto was built in 1476 by Pope Sixtus IV on the site of a previous chapel known as S. Maria de Spazolaria.

The Pope placed his coat of arms on the building and an inscription with his name on the lintel of the door. A smaller inscription said that the chapel was meant for those

who wished to pray for the souls of their kin in Purgatory.

Oratorio di S. Margherita is a chapel which is rather hard to find; it is located in a tower of the Roman

walls: the tower, unlike the others, has some windows on the inner side of the walls and a sort of bell tower

at its top. Because of its overall aspect it was called Prigione (prison) di S. Margherita. The chapel was quite popular in the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries, but later on its existence was forgotten.

Next plate in Book 3: Basilica di S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura.

You have completed Day 1! Move to Day 2.

Next step in your tour of Rione Monti: Porta S. Giovanni.

Excerpts from Giuseppe Vasi 1761 Itinerary related to this page:

Basilica di S. Croce in Gerusalemme

Fu questa eretta dall'Imperatore Costantino ad istanza di s. Elena sua madre nel suo

palazzo Sessoriano per collocarvi il legno della ss. Croce, che aveva portato da

Gerusalemme, e per˛ ne prese il titolo ed il nome. Dopo molti riattamenti fu ultimamente

rinnovata dal Pontefice Benedetto XIV. col disegno del Cav. Passalacqua Messinese, ed Ŕ

ornata con pitture, e stucchi dorati; quelle nella volta, nella crociata, e i due laterali a

fresco fatti nella tribuna sono di Corrado Giaquinto; il quadro nella prima cappella a

destra Ŕ di Gio. Bonatti, quello nella seconda di Carlo Maratti, e nella terza dipinse

il Cav. Vanni. Il ritrovamento della ss. Croce dipinto nella tribuna sembra maniera di

Pietro Perugino. Dalla porticella a destra si scende ad una devota cappella divisa in due,

una dedicata alla ss. PietÓ, e l'altra alla s. Imperatrice, nella quale ella aveva fatto

riporre della terra portata da' luoghi santi di Gerusalemme: perci˛ non Ŕ lecito di

entrarvi le donne, ed Ŕ ornata di mosaici e di marmi. I quadri ne' tre altari sono di

Pietro Paolo Rubens, e le pitture a fresco del Pomaranci. Il bassorilievo della PietÓ Ŕ

opera di autore incerto, ed il deposito del Cardinal Besozzi Ŕ d'Innocenzo Spinazzi.

Tornando poi in chiesa, il quadro del primo altare Ŕ di Luigi Garzi, ed il s. Tommaso nell'

ultima Ŕ di Giuseppe Passeri. ╚ questa una delle sette chiese, ed Ŕ ufiziata da' monaci

Cisterciensi. Lo stradone d'incontro, che porta alla basilica di s. Maria Maggiore,

fu fatto da Sisto V. e quello a sinistra, che va al Laterano, dal mentovato Benedetto XIV.

|