All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in March 2020. The photos were taken in April 2012 and March 2019.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in March 2020. The photos were taken in April 2012 and March 2019.

Carthago (Carthage) in the Museums

Carthago (Carthage) in the MuseumsYou may wish to see an introductory page to this section or pages on the Punic memories and the Roman period of Carthage first.

National Museum of Antiquities of Algiers - exhibits from Carthage: (left) relief portraying Venus, Mars Ultor and Julius Caesar; (right) Emperor Hadrian; it is almost identical to a bust found at Sousse

In 1856 Léon Roches, French consul in Tunis, donated a fragment of an altar relief found at Carthage to the Museum of Algiers. It was part of a monument built by Emperor Augustus.

The head of the statue of Emperor Hadrian was found by Jean-Baptiste Evariste Charles Pricot de Sainte-Marie, another French diplomat, in a Temple to Serapis during excavations carried out in 1873-1876. He found also some mosaics at Uthina.

British Museum: fragments from a IVth century AD floor mosaic from Carthage depicting the Seasons and the Months; the portrait of a season in a medallion was thought to represent Queen Dido; you may wish to see a comparison between this mosaic and a contemporary one from Sidi Ghrib which retained some nudity

In 1856-1858 Nathan Davis, an English traveller and archaeologist, conducted excavation campaigns at Carthage and Utica. The following excerpts are taken from Carthage and her Remains which Davis published in 1861.

Early on the following morning, whilst some of the

men were busily engaged in washing the cleared portion

of pavement, it suddenly struck me that there must be

more of it under the opposite mound, to the left of

the trench. The reason which led me to this conclusion

was a very natural one. The female colossal bust was

in the angle; it therefore did not require much ingenuity to find out that there must have been similar ones

in the other three corners. From the size of the design,

the position of the priestesses, and particularly from the

fragment found by the custodian, it was clear that the

mosaic extended in that direction. (..) The fame of my discovery was quickly spread abroad,

and reached even the ears of his highness himself,

through some officious Europeans, who, I afterwards

learnt, told the Bey that one of the colossal heads

represented Dido.

British Museum: other fragments from the mosaic depicting the Seasons and the Months; November is portrayed as a priestess of Isis holding a sistrum; the subject was depicted also in a mosaic found at Thysdrus

When the remains of this gorgeous pavement were washed, the colours stood out as fresh, and bright, as if the artist's hand had only just been removed. Then the skill which is so strikingly manifested in the exquisite designs, as well as the perfection of art exhibited in the light and shade of the figures, called forth the unbounded admiration of every one who had the advantage of visiting them on the spot. Davis

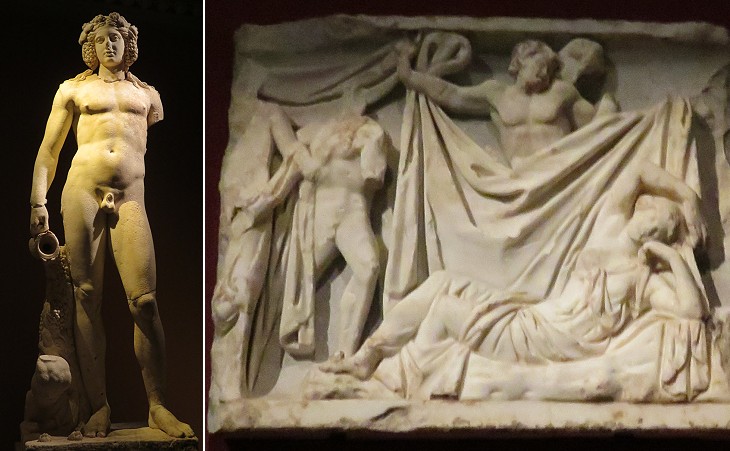

Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna: IInd century AD exhibits: (left) statue of Dionysus/Bacchus from Carthage; (right) fragment of sarcophagus with a scene portraying Dionysus/Bacchus coming across sleeping Ariadne from an unknown location

Other works of art from Carthage were sent to Europe as gifts. In 1868 a statue of Dionysus/Bacchus was found by the French in Algeria. In 1873 Mustapha Khaznadar (Treasurer), a sort of Prime Minister of Sadok Bey, the last fully independent Bey of Tunis, donated a similar statue of the god to Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, together with the fragment of a sarcophagus. Other similar diplomatic gifts were made by the Khedivés of Egypt and by the Ottoman Sultans.

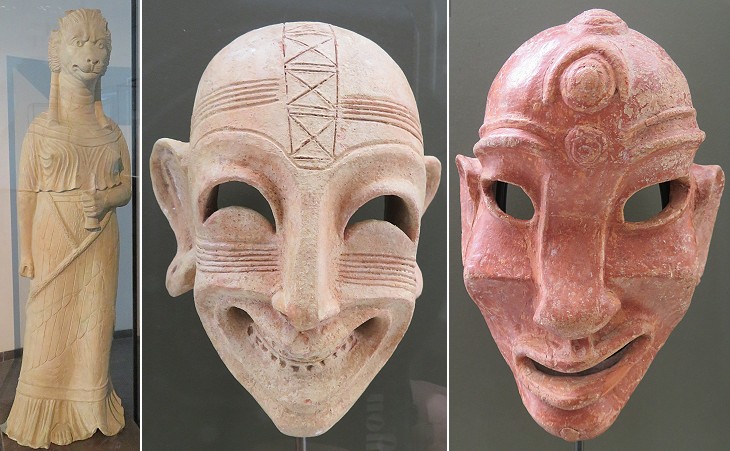

Museum of Bardo: (left) Tanit, lion faced Punic goddess; (right) two Punic masks

After the establishment of the Protectorate over Tunisia in 1881, French authorities began a series of archaeological campaigns and in 1888 decided to utilize one of the palaces of the beys on the hill of Bardo, south of Tunis, to create a large national museum (Musée Alaoui, then Museum of Bardo). The excavations at Carthage were not limited to the more superficial layers of the Roman town and they led to unearthing remains and works of art of the Punic one.

Louvre Museum in Paris: IVth century BC Punic sarcophagi

Some reliefs and statues which were found at Carthage prior to 1881 were donated to the Louvre Museum in Paris, but some of them were lost when Magenta, the ship which carried them, sank in the port of Toulon in 1875, because of an accidental fire. The practice did not entirely stop with the establishment of the Bardo Museum. In 1902 a group of very ancient fine sarcophagi was discovered in a Punic necropolis near the Antonine Baths; two of them were donated to the Louvre in 1906. They portray upper class people, perhaps priests and priestesses, and reflect a pattern which developed in Phoenicia, the country of origin of the Carthaginians, but was eventually influenced by contacts with the Greeks.

Museum of Bardo: Altar of Gens Augusta which was found in 1916 at the foot of the Acropolis: (left) Aeneas fleeing Troy; (right) personification of Rome, similar to one on the pedestal of Colonna di Antonino Pio

At a time when very few travellers visited the interior of the country and local authorities were not aware of the artistic and historical values of archaeological findings, the decision of having a large museum in Tunis made sense. Today the fact that such a large part of the national heritage is concentrated there shows the drawbacks of that decision, i.e. the removal of works of art from their original location, with the only major exception of Sousse where an archaeological museum was established as early as 1898.

Roman Carthage was founded in 29 BC by Emperor Augustus with the name of Colonia Iulia Concordia Carthago. In 13 BC the Senate of Rome decided to consecrate an altar to Pax Augusta, in which the Emperor and his enlarged family (gens) were portrayed while attending a religious procession. A few years later P. Perellius Hedulus, Sac(erdos) Per(petuus) (lifetime high priest) of Carthage dedicated a temple to Gens Augusta; in its ruin archaeologists found an altar in Lunense (Carrara) marble which was finely decorated with low reliefs; it most likely came from Rome.

(left to right): 1), 2) Museum of Bardo: Apollo Citharede found at the theatre; likely portrait of Empress Annia Faustina Juniore, wife of Emperor Marcus Aurelius; 3), 4) Museum of Carthage: two statues portraying Victory which were part of a monument built on the acropolis, probably to celebrate Marcus Aurelius

Some of the early archaeological campaigns at Carthage were conducted by Father Delattre, a member of the Society of the Missionaries of Africa, an order founded in 1868 by Cardinal Charles Lavigerie Archbishop of Algiers. Some of the findings were placed in an Episcopal Museum near the Cathedral on the Acropolis. In 1964 the museum was acquired by the Tunisian State and with the adjoining archaeological area it constitutes the Museum of Carthage.

Overall the number of large statues found at Carthage is rather small when compared to other locations of the Roman Empire, e.g. Perge, and considering the prosperity of the city. This is probably due to the high level of religious violence which marked the IVth century in the region. Donatists and Catholics competed in smashing "idols" and also statues which did not portray gods.

Other exhibits at the Museum of Carthage including the foot of a colossal statue

The focus of the more recent archaeological excavations on the Acropolis has been on finding evidence of the Punic town, rather than on trying to reconstruct the Roman Forum; fragments of its columns and statues are scattered about outside the museum.

Museum of Bardo: decorations in stucco and gypsum of a mausoleum found at a Roman cemetery in the western part of Carthage (IInd century AD) by Father Delattre in the 1880s

A small cemetery at the foot of the Acropolis was reserved to members of the Roman administration of the Province of Africa. The presence of horsemen in the decoration was probably an indication that the dead belonged to the equites, the equestrian order. Initially a military class, the equites acquired a greater role in the imperial household in the Ist century AD and eventually they were often in charge of the financial administration of the provinces. In some cases the reliefs greatly resemble the equestrian bronze statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Rome.

Small statues: (left) Museum of Carthage: Silenus and maenad; (right) Paleo-Christian Museum of Carthage: Jupiter and Ganymede (Vth century)

In the 1980s a small museum was opened at the foot of the Acropolis to house the more recent findings; it is now devoted to the period from the IVth to the VIth century (Paleo-Christian Museum).

The houses of the wealthiest citizens of Carthage were embellished with small statues which came from other parts of the Roman Empire. Aphrodisias, a town in Asia Minor, was known as a centre which shipped statues to the four corners of the empire. Scenes related to Dionysiac festivals and hinting at some lasciviousness were very popular and, as in the statue found at Carthage, they did not necessarily portray a specific episode of the Greek myth (see small bronze statues of Silenus from Herculaneum).

When the Christian Emperors forbade the ancient beliefs, the subjects for small statues changed, although they were still linked to the pre-Christian world.

The statue of Jupiter and Ganymede is far from clearly stating the relationship between the god and the beautiful boy. It resembles statues of Orpheus taming the animals, another popular subject during the Late Empire (see that found at Sabratha).

Museum of Bardo: Sarcophagus of the Four Seasons (IVth century)

Cremation was the traditional Roman method of corpse disposal. Inhumation and the use of sarcophagi were probably introduced in the Ist century AD, but they became standard practice only after the full conversion of the city to Christianity. The sarcophagus shown above portrays the Four Seasons as boys. The dedicatory inscription was not found, but it is likely that the deceased was a Christian because Winter was portrayed as the Good Shepherd, although this can be noted also on some Pagan sarcophagi of the same period, e.g. at Empuries in Spain.

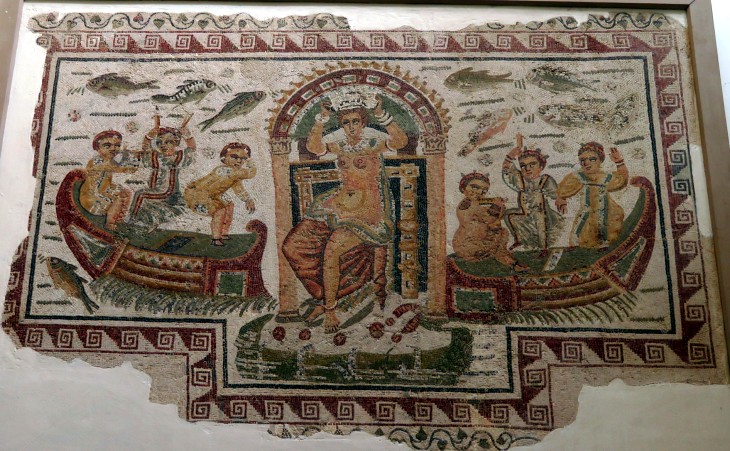

Museum of Bardo: Coronation of Venus (IVth century); see a similar mosaic at Villa del Casale in Sicily

Mosaics are by far the most impressive works of art found at Carthage and in general in Tunisia. They are usually very large as they covered the floors of entire courtyards or large halls.

Sea gods and creatures were a very popular subject throughout the whole of the Roman Empire (see those at Antioch), but the number of mosaics found at Carthage is such that the range of subjects is extremely wide.

The inhabitants of Roman Carthage had a taste for highly coloured mosaics which put to test the skill of mosaicists. In this mosaic where Venus is portrayed halfway between a Greek goddess and a Byzantine empress, the artist was confronted with a particularly complex scene with six dwarfs amusing Venus.

Museum of Bardo: detail of a mosaic portraying four anglers

Sometimes mosaicists best showed their talent in representing scenes of life they knew very well. Angling was a popular pastime also in antiquity as testified to by the many mosaics portraying anglers, e.g. at Leptis Magna and Thugga and by a silver bowl found in Algeria.

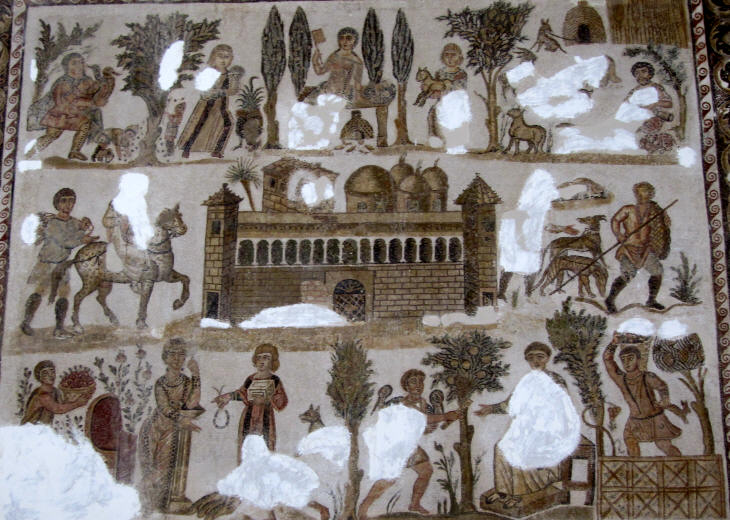

Museum of Bardo: Dominus Julius' Estate (late IVth century)

Some mosaics provide a valuable insight into the society and its economy. Dominus Julius was a rich landowner who lived at Carthage, but the mosaic depicts his farm/countryside residence. He is portrayed sitting in the lower right corner while he receives a message addressed to him. His wife is portrayed opposite him while she is attended by a servant. The large farm was fortified with towers and high walls without openings, an indication that at the time security was a worry. The domes are likely a sign of private baths. The building is surrounded by scenes showing farming and hunting activities in the four seasons. With one exception all personages are fully clothed, an indication that classic nakedness was out of fashion. The overall purpose of the mosaic was to show the wealth of Julius in all its facets, including the clothes of his servants. You may wish to see a Roman Villa at Sidi Ghrib which most likely belonged to another rich landowner who lived at Carthage and a mosaic from Uthina which shows scenes of life in the countryside.

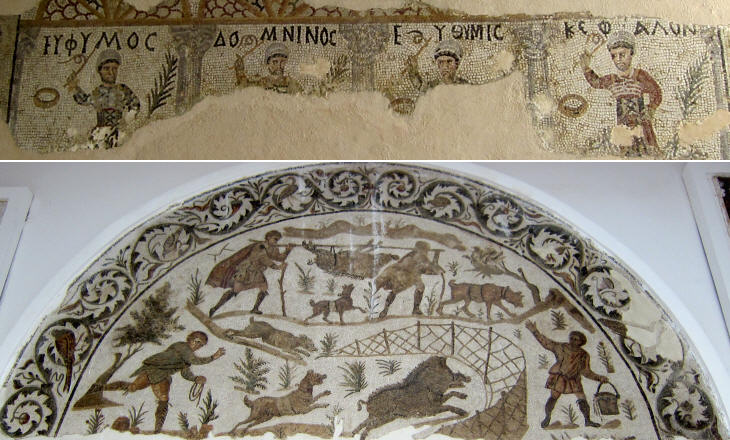

(above) Paleo-Christian Museum of Carthage: Mosaic of the Four Greek Auriga (chariot drivers) (late IVth century); (below) Museum of Bardo: boar hunting scenes (late IVth century)

According to tradition when the Vandals conquered Carthage in 439 the city was not defended because all the soldiers and the inhabitants were watching the races at the hippodrome, traces of which have been identified near the amphitheatre. Chariot races were popular in Rome, but more so at Constantinople. The chariot drivers portrayed in the mosaic were most likely from that city as their names were written in Greek, something very unusual because in Africa this language was very rarely used in inscriptions. They wore the brightly coloured costume (red, blue, white and green) of their faction (see a large mosaic depicting a chariot race at Lyon and one showing the raising of race horses at Sousse).

Boar hunting was a popular subject in the decoration of sarcophagi; gods and heroes were portrayed hunting with poles (see a beautiful example at Eleusi), but in this mosaic the focus is on the technique used at the time which was based on dogs and nets. The technique was used in particular for capturing alive wild beasts (as shown in a mosaic at Hippo Regius) which were then sent to Carthage, Rome and other large cities of the Empire for venationes in the amphitheatres.

(left) Museum of Bardo: Diana and Apollo hunting a crane (late IVth century); (right) Museum of Carthage: detail of a floor mosaic with scenes of "venationes" or hunting of wild beasts

The same site which housed the boar hunting mosaic had another mosaic with a hunting subject. In this case there was a reference to the Classic World, although the two gods were represented in a rather unusual still posture inside a temple, as if they were being offered a crane as a sacrifice. Diana has a halo around her head which is not part of her traditional iconography (it can be seen also in a mosaic at Bulla).

The Museum of Carthage displays three fragments of a floor mosaic based on a geometric pattern of leaves framing small scenes, a technique which was often utilized for very large floor mosaics e.g. the Triumph of Neptune from Sousse which has 56 similar medallions.

Museum of Bardo: "panther skin rug" from Carthage (IIIrd/IVth century); a mosaic portraying a Barbary lion can be seen in the image used as background for this page

It is known that cartoons depicting decorative patterns and subjects circulated among the workshops of mosaic makers so that very similar mosaics have been found in very different parts of the Roman Empire. Occasionally, either at the initiative of the landlord or of the craftsman, new designs and subjects were experimented. The house of Carthage where this mosaic was found might have belonged to a person who actually hunted and killed a panther (a term indicating lions, tigers, leopards and big cats) in the Atlas Mountains. Similar to a retired XIXth century British officer from Bengal, he wanted the beast skin to decorate a hall of his house. The mosaic was a more hygienic way of achieving this result.

(left) Museum of Carthage: the Lady of Carthage; (right) Asperius Chapel (reconstructed at the Antonine Baths - VIIth century)

A total depart from the iconographical patterns of antiquity occurred during the VIth century. Carthage was conquered by the Byzantines in 533. This per se did not have a major devastating impact on the city as the Vandals were unable to oppose the invasion, but in 541-542 a plague almost halved its population. The long Greek-Gothic War (535-553) in Italy deprived Carthage of its traditional markets.

The seriousness of the Lady of Carthage, probably a saint, testifies to the gravity of the situation.

A later mosaic on the floor of a funerary chapel shows an almost naive attempt to portray some birds. Carthage was approaching its final days. It was destroyed by the Arabs in 698.

Museum of Carthage: VIth century mosaic found at Carthage in a Christian site of prayer: it depicts a studded cross in a circle with birds and lambs and four personages around it, most likely the Evangelists, an iconographical pattern which can be noticed in contemporary mosaics at Ravenna

Move to: Carthage - Punic memories or to Roman Carthage.

Plan of this section:

Introductory page

Aphrodisium and Sullectum

Bulla Regia

Carthage

Clypea (Kelibia)

Kerkouane (Punic)

Mactaris

Musti

Neapolis

Pheradi Majus

Pupput

Sicca Veneria

Sidi Ghrib Roman Villa

Simitthus

Sufetula

Thapsus and Leptis Minor

Thignica

Thuburbo Majus

Thugga

Thysdrus

Uppenna

Uthina

Utica

Ziqua

Mosaics in the Museum of Bardo

Mosaics in the Museum of Sousse