All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in November 2023.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in November 2023.

- Ancient Rome

- Ancient RomeIn this page:

Gneus Pompeus (Pompey), a New Leader

The First Triumvirate: Caesar, Crassus and Pompey (Saepta Iulia)

Conquest of Gallia (Clivus Capitolinus and Basilica Iulia)

Civil War

The First Imperator

Iconography

Commoners:

...But indeed, sir, we make holiday, to see

Caesar and to rejoice in his triumph.

Marullus:

Wherefore rejoice? What conquest brings he home?

What tributaries follow him to Rome,

To grace in captive bonds his chariot-wheels?

You blocks, you stones, you worse than senseless things!

O you hard hearts, you cruel men of Rome,

Knew you not of Pompey?..

William Shakespeare - The Tragedy of Julius Caesar - Act I

After the resignation from the consulate of Silla,

the remaining followers of his former rival Marius regrouped

in Spain and, building on the national feelings of the locals, they proclaimed the autonomy of the two

Roman provinces, which, with the exception of the mountainous northern region, included the whole Iberian peninsula. The Senate sent to Spain Gneus Pompeus (Pompey), a military commander who had already defeated

the followers of Marius in Africa and Sicily and who for these victories had received

the title of Magnus (the Great).

It took Pompey six years (from 77 to 71) to restore the authority of Rome in Spain: on his way back to Rome he

defeated Spartacus, a former gladiator in the amphitheatre of Capua and the leader of a rebellion of slaves, who for two

years had terrorized Southern Italy. He became so popular that he was appointed consul together

with Marcus Licinius Crassus, a sort of modern tycoon: they both acted to reduce the

rift between the Roman factions which had supported either Silla or Marius.

Marcus Licinius Crassus had become immensely rich by buying houses destroyed by

fire or otherwise

damaged and by replacing them with new buildings for the upper classes. These new

houses were designed, built and decorated by his skilled slaves.

In 67 Pompey was given extraordinary authorities to put an end to the

raids of pirates along the southern coasts of today's Turkey (see some pages on the Coast of the Pirates).

Pompey not only eradicated the pirates' threat on the trade routes of that part of the Mediterranean,

but he also defeated Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, and expanded the authority of Rome in the

region: he reorganized the Roman territories in four provinces: Pontus (Black Sea coast); Asia (Aegean Sea coast);

Cilicia (Mediterranean Sea coast) and Syria, corresponding to today's Syria and Lebanon.

Many small neighbouring countries (e.g. Armenia, Galatia, Colchis, Commagene, Judaea) sought the protection of Rome against the threat of the Parthians, who ruled

on a vast territory which included today's Iran, Iraq and parts of Central Asia.

(left) Copy of a statue which is assumed to portray Pompey in the courtyard of a modern building located in the

area of Teatro di Pompeo (see some engravings showing the statue); (right) menu of a restaurant

in Palazzo Pio, where one can see walls of the theatre

The great curiosity here, is the colossal statue of Pompey; which is said to be the very statue, at the base of which, - "Great Caesar fell;" - though the objection to a naked heroic statue, as the representative of a Roman senator, is, perhaps, fatal to its identity; - and then, the holding the globe in his hand, is not in republican taste; - this action speaks the language of a master of the world, and brings the statue down to the days of the empire.

Henry Matthews - Diary of an Invalid - 1817/1818

Upon his return to Rome, Pompey decided to celebrate his victories by erecting a temple to Venus Vincitrix (victress);

this was at least the official intent of the theatre he built near today's Campo dei Fiori; because some members of the

Senate were suspicious of anything which had a Greek flavour and this

included comedies and tragedies, Pompey placed at the very top of the cavea

(the hemicycle where the audience sat) a small temple and the cavea

was explained as a gigantic flight of steps leading to it.

The area where the theatre was built

became (due to its proximity to the river), a heavily populated quarter of Papal

Rome and the ancient stones were used as building material for many medieval and Renaissance houses.

The site of the cavea is still evident in the shape of a curved tall building near Palazzo Pio.

The foundations of this palace made use of the arches supporting the cavea.

cicerone n. Guide who understands and explains antiquities, etc.

While Pompey was in Asia, Marcus Tullius Cicero, a brilliant lawyer, gained the support of the Senate and

was twice appointed consul. In this capacity he delivered four speeches (Catilinaria), which are

regarded as an example of Roman eloquence; in these speeches he denounced the plot of Lucius Sergius Catilina,

an ambitious patrician, who, after having failed to be appointed consul, was

trying to overturn the republican institutions. The initial words of one of Cicero's speeches Quo usque tandem, Catilina, abutere patientia nostra? (until when Catilina are you going to strain our patience?) are still used to mean that

a certain person is exasperating us (the abridged form usque tandem is more common).

Catilina fled Rome and was eventually killed with most of his followers. For a moment Cicero seemed the homo novus (new man) of Roman politics, but with the return of

Pompey he soon lost importance.

Some of the senators had become hostile to Pompey who renewed his alliance with Crassus; in 60 the two entered into

a sort of agreement of mutual support with Gaius Julius Caesar, a former supporter of Marius,

who, after a period of exile, had managed to be appointed proconsul (governor) of Hispania Ulterior,

one of the two Roman provinces in Spain, where he had made a fortune.

Historians have called this agreement the first triumvirate,

but it was only a private pact, with no formal recognition by the Roman institutions.

Caesar, supported by Crassus and Pompey, was appointed consul and in this capacity he

proposed laws which favoured the veterans who had fought in Asia with Pompey. He was then appointed proconsul for five years of Gallia Cisalpina, Gallia Narbonensis and Illyria (Northern Italy, Southern France and today's Croatia and Slovenia).

In 55 the agreement was renewed: Caesar retained his provinces, while Pompey and Crassus controlled Spain and Syria respectively.

(left) Curia Julia; (centre) detail of its pavement; (right) ruins of Saepta Julia near the Pantheon

In the early republican period the Senate had a membership of one hundred, but over time this number was increased and eventually it

was fixed at 600 by Silla. Curia Hostilia, the old building where the senators met, had not enough room for them all. Silla built

a new hall (Curia Cornelia) on the site of today's SS. Luca e Martina, but the new building lasted only a few years because it was destroyed by a fire in 52.

It was rebuilt adjacent to the previous building by Julius Caesar who gave it his name (Curia Julia); the building was largely restored by Emperor Diocletian, following a fire. In the VIIth century AD the Senate hall was turned into a

church; in 1931-37 the bare structure of the building was cleared of all additions: the statues and marbles which decorated the façade, as well as

the portico are lost; the bronze doors were moved

to S. Giovanni in Laterano. Below the pavement of the church, archaeologists found parts of the old Roman one and, based

on their design, they have reconstructed it.

The senators did not raise hands to cast their votes, but they grouped on one side or the other of the rectangular

hall to express their agreement or disagreement with a certain proposal. While the large majority of the assembly halls

where senators meet today have the shape of a hemicycle, the British House of Commons Chamber, designed in the early XIXth century, has

a rectangular shape.

Caesar took care also of the meetings of the Romans in general,

when they were called to elect their tribunes and other magistrates. The Saepta Julia, a large rectangular open space flanked

by two porticoes, lay under the houses of Rione Pigna; a small section of the western portico came to light

when some houses built next to the walls of the Pantheon were pulled down (see a fragment of Forma Urbis, a marble plan of Ancient Rome showing one of the porticoes).

The Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis and in particular

the southern part of the Rhone Valley was under constant threat of raids made by German tribes

coming from the north: also the Helvetians, the inhabitants of today's Switzerland, were a

source of trouble for the Roman settlements.

In 58 Caesar started a series of campaigns, which, from the initial objective

of protecting Gallia Narbonensis, year after year expanded the territories controlled by the Romans

until they reached what later on became the "natural" border of the Roman Empire: the River Rhine.

Caesar narrated in a very factual manner his campaigns in De Bello Gallico (about the war in Gallia).

He first defeated the Helvetians, then

forced back the Germans beyond the Rhine; to consolidate his victories he moved further north in today's Belgium and

from there twice landed on Britain. He often relied on the divisions among the various tribes who

lived in the area: the saying Divide et impera or Divide ut imperes is generally attributed to Machiavelli,

but certainly Caesar had it in mind when one by one, either in the

battlefield or by diplomatic means, he managed to make the local chiefs

accept the Roman authority.

In 53 however, taking advantage of the temporary

absence of Caesar, the Gauls decided to forget their differences and rebelled. Their leader

was Vercingetorix, chief of the tribes living in today's Auvergne, a mountain region in the

centre of France.

At first the Romans were surprised by the impetus of their enemies, but Vercingetorix

made the mistake to retreat after a victory to the town of Alesia. Caesar laid siege

to it and the hopes of Vercingetorix to receive help from his allies soon faded away.

The Romans had a superior knowledge in digging trenches, erecting palisades and in general in fortifying their camps.

The Gauls vainly tried to unlock the Roman defensive system; in the end they gave up and Vercingetorix surrendered.

By the year 51 Caesar restored the authority of Rome over the whole of Gallia.

(left) Clivus Capitolinus, the street linking Foro Romano with Campidoglio; (right) Basilica Julia (behind it Tempio di Castore e Polluce)

We usually take for granted that streets are paved; it was not so in the ancient

times: this explains why the pavement by Caesar of Clivus Capitolinus, a short winding street linking the Capitoline hill with the

Roman Forum, was regarded as one of his most laudable initiatives for the embellishment of Rome.

The large worn out stones are no longer well aligned and there are wide gaps

between them, yet they demonstrate the sound techniques the Romans used to ensure the stability of their roads.

Caesar gave his name (or to be more precise Julia, the name of his gens, family)

to the largest building of the Roman Forum, a basilica which replaced a previous one. In addition to law courts, it contained many tabernae (taverns, but also shops). The rows of columns divided the basilica into five naves:

a pattern which

was later on followed in the design of S. Giovanni in Laterano, one of the earliest Christian churches.

In May 53 the triumvirate agreement lost one of its subscribers. Crassus, who was proconsul in Syria, moved with seven legions against the Parthians. He had a small cavalry of 1,000 Gauls under the command of his son Publius who had fought with Caesar: the rest of the cavalry was provided by the allied local kings. In the desert near Carrhae, in northern Mesopotamia (today's Harran in Turkey at the border with Syria), the Romans attacked the Parthians whose army was mainly composed of cataphracts (armoured cavalry) and mounted archers. The Roman light infantry was forced back to its initial position by clouds of arrows. Crassus to gain time to reorganize his troops sent his cavalry against the enemy, but the allied kings fled the battlefield: Publius and his Gauls forced the mounted archers to retreat, but the Parthians were able to throw their arrows backwards (so a Parthian shot is a remark or glance reserved for the moment of departure; over time the saying became parting shot). The Roman cavalry suffered heavy losses and it was eventually surrounded by the enemy: Publius, fearing to fall prisoner, killed himself. Crassus made a last attempt to deploy his troops in an attacking scheme, but the armoured Parthian cavalry put them in disarray. Crassus lost his life and with him most of his legionaries; the Parthians managed to take the legion insignia, a very shameful event for the Romans, whose eastwards expansion was blocked for more than 150 years.

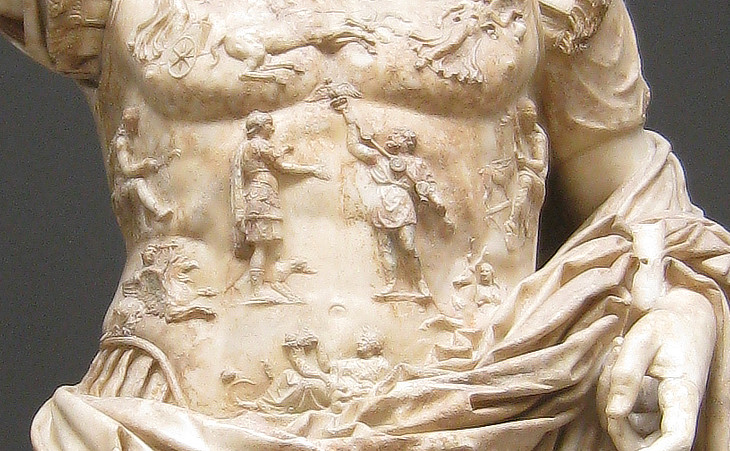

Musei Vaticani - Braccio Nuovo: detail of the statue of "Augusto di Prima Porta" showing the "insignia" lost at Carrhae being returned to the Romans

After the death of Crassus, Caesar and Pompey gradually moved from alliance to

confrontation. Pompey returned to Rome and gained the support of the Senate: in 52 he was appointed

consul sine collega (sole consul) and given wide powers; for a while the confrontation between Caesar

and Pompey remained in the legal/political framework; Caesar did not move from his provinces, but through his envoys

and supporters challenged the decisions of the Senate and of Pompey; in January 49 the Senate ordered him to disband his legions and entrusted the defence of the

Republic to Pompey.

There were, then, two passages over the Rubicon anciently, the one by the Via Emilia, the other, about a mile lower down, or nearer the sea, on the direct road from Ravenna to Rimini. This then was the passage, and this is the celebrated spot, where Caesar stood, and absorbed in thought, suspended for a moment his own fortunes, the fate of Rome, and the destinies of mankind. (..) Here Caesar passed, and cast the die (alea iacta est), that decided the fate, not of Rome only, of her consuls, her senates, and her armies, but of nations and empires, kingdoms and republics, that then slept in embryo in the bosom of futurity.

John Chetwode Eustace - A Classical Tour through Italy in 1802

Caesar's reaction was swift: in a matter of days he crossed with his army the Rubicon, a small stream near Rimini which marked the

boundary between the province of Gallia Cisalpina and the extended metropolitan territory of Rome:

by doing this he violated the orders of the Senate: an act he could not undo, therefore to cross the Rubicon means becoming committed to a certain enterprise.

Pompey had no time to arrange a defence of Rome and preferred to leave the city for Greece with the majority of the senators to organize there

a counter-offensive.

Caesar established in Rome a government he could rely upon. He then

showed his ability to make quick decisions and rapidly move from one province to the other. Pompey had been

for years proconsul in Spain and had there many supporters:

in a matter of a few months Caesar subdued them and in January 48 he turned his attention towards Greece,

where Pompey had gathered a large army. The final battle took place at

Pharsalus, in Thessaly: Pompey was defeated and sought refuge in Egypt, the last large

Mediterranean country which had not yet been touched by the Roman expansion.

Caesar decided to chase Pompey even there. With a small army he

landed in Alexandria (the site of his camp is still remembered

by the French name Camp de César of a neighbourhood), where to his great disgust, he was offered by Pharaoh

Ptolemy XIII (*) the head of Pompey.

Theodotus of Chios, the rhetoric tutor of Ptolemy, persuaded the Pharaoh to kill Pompey, thus

violating the laws of hospitality, to

gain Caesar's support in his quarrel with his sister and wife Cleopatra. Caesar tried

to reconcile the two, but eventually, after falling in love with Cleopatra who bore him a child (Caesarion), he sided

with her and defeated Ptolemy. Cleopatra, who wished to become the sole ruler of Egypt,

was however advised by Caesar to marry another brother (Ptolemy XIV).

Caesar had to leave Egypt to quell the last threats to his uncontested rule:

a rebellion in Pontus was so quickly quenched that Caesar summarized this campaign

in three words Veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered); he then defeated at Thapsus

the last supporters of Pompey in Africa.

In 46 Caesar celebrated in Rome four triumphs for his victorious campaigns and received the following

additional names Gallicus, Ponticus, Alexandrinus and Africanus.

Remaining portico of Foro di Cesare; (behind it some tabernae)

Caesar gained a lot from being the proconsul of Gallia and while he was still busy there he bought through an intermediary the buildings and the land to the north of the Roman Forum: his aim was to dedicate a temple to Venus Genitrix (parent/mother), as his family claimed to directly descend from Aeneas and therefore from his mother Venus; the temple was preceded by a rectangular square flanked by two porticoes, one of which is still clearly identifiable. On his return to Rome in 46 the temple was solemnly inaugurated.

Caesar was aware that, behind the apparent enthusiasm with which his triumphs

had been greeted, there were some long standing contrasts in the Roman society, due to

different economic interests, which could undermine his power.

He therefore introduced several changes in the Roman institutions: he granted Roman

citizenship to Gallia Cisalpina (Northern Italy), the faithful province which had supported

him when he was in conflict with the Senate; he diluted the authority of this body by increasing

its membership to 900 and by establishing that some of its members should represent

the provinces; he reduced the maximum time of incumbency of proconsuls in a province to prevent

them from following his example and building there a personal power.

He forced the Senate to endorse beforehand his decision and to appoint him consul

for ten years and give him for his lifetime the title of imperator, a word

which originally meant great military commander and did not correspond to a specific

authority (imperium = command/order - see the pedestal of a statue of a IInd century BC consul who was given the title of imperator).

Caesar's reforms were not limited to politics;

he extended the application of Roman laws to the provinces,

thus favouring trade and other businesses which were supported by a common set of rules;

he punished more severely the civil servants who extorted bribes to grant

authorizations which were due; his more lasting reform was the introduction of a new calendar (named after him Julian), based

on the astronomical calculations of the Egyptians and which is still

used by some Christian churches which have refused the changes to the calendar

made by Pope Gregory XIII in 1573 (see a Roman farming calendar).

He behaved like a monarch and although he refused the crown three times, the fact

that he had received the senators remaining seated before the Temple to Venus, as if he were a god himself,

was highly criticized by the most conservative part of the Roman society.

Under the pretence of restoring the old republican institutions a

group of senators and other citizens, dissatisfied with the way Caesar had assigned

positions and favours, plotted to kill him.

(left) Ruins of the entrance to Curia Pompea a large courtyard

leading to Teatro di Pompeo,

behind Temple C of Area Sacra di Largo Argentina: here Caesar was stabbed; (right) flowers on Ara di Cesare,

an altar in the Roman Forum near Regia, the former royal palace, where Caesar's funerals took place

Caesar maybe suspected what was going on, but (on the ides (**) of March of the year 44) he discarded the warnings of Calpurnia, his wife, not to go to a meeting with the Senate; he had also been told to beware of the ides of March; at the entrance to Curia Pompea, a large courtyard leading to Teatro di Pompeo, Caesar was stabbed to death, right under a statue of Pompey, his former ally and rival. When he saw Junius Brutus, whom he regarded as a child of his own, among the conjurors he cried: Quoque tu, Brute, fili mi (you too Brutus, my child): these were his last words.

THE IDES OF MARCH

Guard. O my soul, against pomp and glory.

And if you cannot curb your ambitions,

at least pursue them hesitantly, cautiously.

And the higher you go,

the more searching and careful you need to be.

And when you reach your summit, Caesar at last -

when you assume the role of someone that famous -

then be especially careful as you go out into the street,

a conspicuous man of power with your retinue;

and should a certain Artemidoros

come up to you out of the crowd, bringing a letter,

and say hurriedly: "Read this at once.

There are things in it important for you to see."

be sure to stop; be sure to postpone

all talk or business; be sure to brush off

all those who salute and bow to you

(they can be seen later); let even

the Senate itself wait - and find out immediately

what grave message Artemidoros has for you.

Constantine Cavafy - translation by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard

Antony

O mighty Caesar! dost thou lie so low?

Are all thy conquests, glories, triumphs, spoils,

Shrunk to this little measure? Fare thee well!

I know not, gentlemen, what you intend,

Who else must be let blood, who else is rank:

If I myself, there is no hour so fit

As Caesar's death hour, nor no instrument

Of half that worth as those your swords, made rich

With the most noble blood of all this world.

I do beseech ye, if you bear me hard,

Now, whilst your purpled hands do reek and smoke,

Fulfil your pleasure. Live a thousand years,

I shall not find myself so apt to die:

No place will please me so, no mean of death,

As here by Caesar, and by you cut off,

The choice and master spirits of this age.

William Shakespeare - The Tragedy of Julius Caesar - Act III

The following links show works of art or other visual media portraying characters and events

mentioned in this page (they open in another window):

Spartacus was totally ignored for centuries until, due to his rebellion, he was seen as a

forerunner of the early XXth century fight of the working class for better living conditions.

See Kirk Douglas as Spartacus and the Spartak Moskow team of 2019-2020, one of the many soccer clubs named after Spartacus.

Cicero was portrayed

while unveiling Catilina's plot by Cesare Maccari (1880) in the Italian Senate at

Palazzo Madama.

Several events of Caesar's life inspired artists and film-makers:

Caesar accepting the surrender of Vercingetorix 1899 painting by Lionel-Noël Royer.

Cleopatra before Caesar by Jean-Leon Gérôme (1824-1904).

Claude Rains and Vivien Leigh as Caesar and Cleopatra.

Sir John Gielgud, Marlon Brando and Greer Garson as Caesar, Antony and Calpurnia (they are also shown in the image used as background for this page).

Death of Julius Caesar at the foot of the statue of Pompey 1798 painting by Vincenzo Camuccini.

(*) The numbering of the Ptolemies varies: some sources indicate Ptolemy XIV as the first husband of Cleopatra (who should be more precisely called Cleopatra VII) and Ptolemy XV as his second husband.

(**) In the Roman calendar calendae indicated the first day of month, nones the 5th or the 7th day, ides the 13th or 15th of the month. In March, May, July, October the ides indicated the 15th. Because the Greeks

did not use the Roman approach for naming the first day of month, the saying on the Greek calends is a roundabout

expression meaning never.

Previous pages:

I - The Foundation and the Early Days of Rome

II - The Early Republican Period

III - The Romans Meet the Elephants

IV - Expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea

Next page:

VI - Augustus