All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in December 2022.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in December 2022.

- Fabriano

- FabrianoYou may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

Piazza del Comune

Some of the buildings in the main square of Fabriano were redesigned in the XVIIth century or more recently, but that with the vertical flags (Palazzo del PodestÓ - 1255) and the nearby fountain (Fontana Sturinalto - 1285) immediately tell the visitor about the wealth of Fabriano in the XIIIth century and its overall medieval character. Unlike many other towns of the Marches, Fabriano was not founded on top of a hill, but in the valley of a tributary of the River Esino which crossed the town. The brook is a pretty small one, but because Fabriano is near its sources, its stream was strong enough to move the blades of water wheels, a source of energy which was skilfully harnessed.

Palazzo del PodestÓ and Fontana Sturinalto

The oldest records about Fabriano go back to the XIth century. It was a Comune, a city-state ruled by its own magistrates. In many Comuni conflicts on the appointment of the ruling bodies of the town were so frequent that it was decided to call in a podestÓ, a foreigner

and ask him to act as chief magistrate for a specified period of time. PodestÓ means "holder of power".

Palazzo del PodestÓ was at the same time a residential palace and a small fortress, as its design and towers show. The battlements are a modern addition aimed at emphasizing its medieval appearance.

Fontana Sturinalto was built by a mason from Perugia and it resembles a small Fontana Maggiore, a famous fountain of that town.

(left) Site of Porta del Piano, one of the gates; (right) a section of the walls inside a private property

At the beginning the fortifications of Fabriano consisted of two small castles on slightly high ground near the brook. In the XIIIth century the whole town was surrounded by walls which had four gates. This enclosure was not upgraded to the needs of cannon warfare and most of it was pulled down in the XIXth century to facilitate the development of the town. Fabriano is still divided into four historical quarters named after the gates which have their own coat of arms.

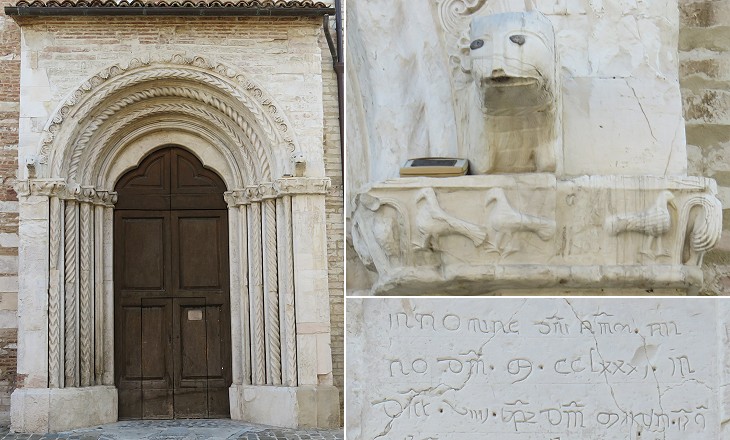

S. Agostino: (left) portal; (right-above) details of the portal; (right-below) 1281 inscription

S. Agostino was built in the XIIIth century, but it was entirely redesigned in 1768, as has occurred to many other monuments of the town which were damaged by a major earthquake in 1741. It retains the original portal with its elegant columns. A small nearby slab shows how much medieval inscriptions had departed from the canons of the ancient Roman ones. It is interesting to note the frequent use of vinculum, a scribal abbreviation consisting in a curved or straight bar above a letter. In this text domini (of the Lord) is written dm with a vinculum over the m. You may wish to see another example of use of this abbreviation (SCA instead of SANCTA) in a VIth century mosaic in Parenzo.

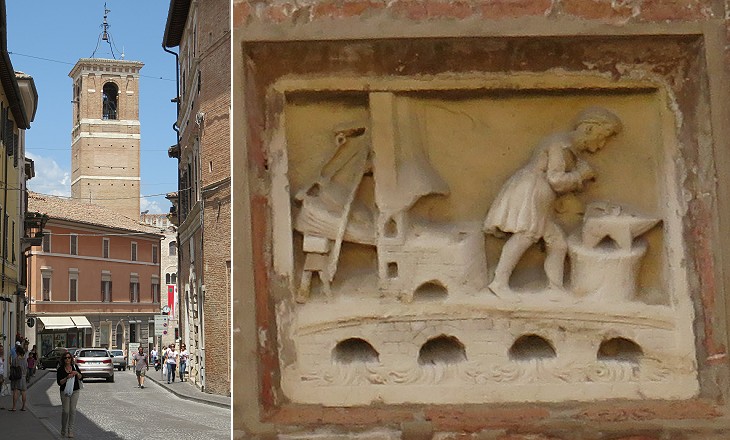

(left) Tower of Palazzo Vescovile; (right) coat of arms of Fabriano on the wall of the tower

In 1728 Fabriano became a bishopric see and its Bishops resided in a palace which incorporated Torre Civica, a XVIth century tower. Many coats of arms of Italian towns are based on symbols of Faith or power (crosses, lions, eagles, etc.), but the inhabitants of Fabriano chose to be represented by their main economic activity: papermaking. Workers in this industry were considered to be a branch of smiths. The bridge is a reference to Fabriano being crossed by a brook.

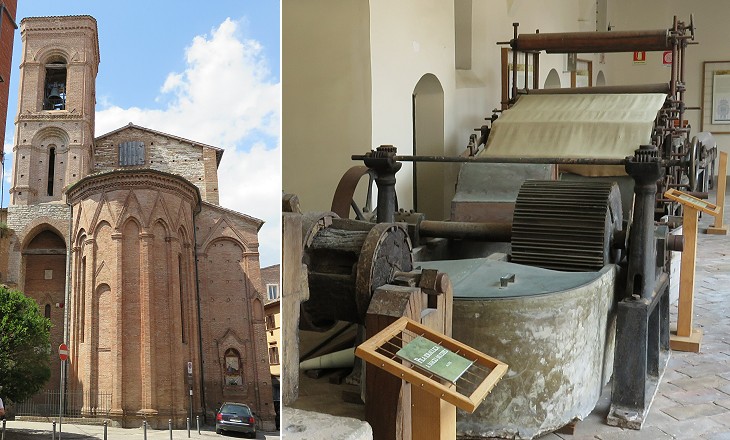

S. Domenico: (left) apse; (right) old machine for papermaking in its convent

S. Domenico is a church which was redesigned in the XVIIIth century, but retains an elegant XIVth century apse. The nearby large convent houses Museo della Carta e della Filigrana, a museum which explains how papermaking developed at Fabriano and which technological improvements (use of animal glues and cotton fibres) made the paper of the town so praised. In 1282 Fabriano papermakers first used filigrana (watermarking) to identify their products.

S. Domenico: the making of a work of art at the 2014 International Association of Hand Papermakers and Paper Artists (IAPMA) Congress which was held in Fabriano

During the XVIth century 60 paper mills were recorded at Fabriano. Then the business declined until it was revived at the end of the XVIIIth century by introducing more modern machinery and working practices. Today papermaking is still a fundamental element of the economy of the town.

(above) Spedale di S. Maria del Buon Ges¨ (1456); (below) part of its long inscription making reference to St. James of the Marches, its founder

This fine Gothic/Early Renaissance building was also known as Ospedale degli Esposti, a term usually indicating children who were abandoned, so most likely it was an orphanage in addition to being a hospital. In 1421 Spedale degli Innocenti, the first modern orphanage/hospital was founded in Florence and Filippo Brunelleschi designed it. The example was followed by many other towns, including Fabriano.

Spedale di S. Maria del Buon Ges¨: fresco over the entrance by a follower of Gentile da Fabriano

Fabriano is the hometown of Gentile da Fabriano (ca 1370-1427) a painter whose wooden golden polyptychs are in many museums of the world, but whose frescoes, including the ceiling of a side nave at S. Giovanni in Laterano are lost. His works influenced many other painters of Fabriano and of the Marches.

Museum at Spedale di S. Maria del Buon Ges¨ (at a temporary exhibition at Scuderie del Quirinale): St. Nicholas of Tolentino, St. Augustine holding the rule of the Order and St. Stephen Protomartyr by Allegretto Nuzi or Nuzzi, a local painter (ca 1360 from S. Agostino)

The Augustinian Order had a particular importance in the region owing to St. Nicholas of Tolentino (1245-1305), a friar who acquired fame for his visions and miracles. The shrine dedicated to him at Tolentino is locally regarded as more important than that of Loreto. The depiction of St. Stephen is due to a passage in The City of God in which St. Augustine describes the miracles wrought at St. Stephen's intercession.

Piazza del Mercato: (above) a XIVth century portico belonging to a hospital; (below) fountain with inscription making reference to Pope Alexander VI

In many Comuni at one point a single family managed to hold the main offices in the government of the town. This practice was often formalized by an amendment in the Comune laws or by a papal or imperial investiture. Such form of government is known as Signoria (lordship/sovereignty). The best known example is Signoria di Firenze by this indicating the power held by the (de)

Medici family in Florence. Their rule was not without challenge and on Sunday April 26, 1478 members of a rival family (the Pazzi) attempted to kill Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici in the Cathedral during Mass. Lorenzo managed to escape and the Medici retained control over Florence.

The Pazzi were not the first ones to act in such a sacrilegious way. In 1271 Henry of Almain in Viterbo and in 1435 all male members of the Chiarelli family (including five children) in Fabriano were killed while attending Mass.

The Chiarelli ruled Fabriano for more than sixty years, but they were overturned by a general revolt. The inhabitants however were unable to regain their freedom and Fabriano ended up by being ruled by a papal envoy who resided in Camerino.

S. Venanzio/Cathedral: XVIIth century works of art: (left) wooden replica of La PietÓ by Michelangelo; (right) stucco decoration of Cappella di S. Carlo Borromeo

S. Venanzio was rebuilt in the XVIIth century and it became the Cathedral of Fabriano in the following one. Its decoration aims at imitating that of Roman churches, but the depressed economy of Fabriano in that period imposed the use of wood and stucco rather than marble.

Fabriano had to share its Bishop with Camerino (1728-1785) and Matelica (1785-today).

(left) S. Onofrio (1727); (centre) S. Nicol˛ (late XVIIth century); (right) Sacro Cuore (1710)

In April 1741 a major earthquake struck Fabriano and other nearby towns. The inhabitants appealed for help to the Papal government, but the state of the economy was very poor and Pope Benedict XIV could only express his grief for the victims and paternal closeness to the survivors. The reconstruction of many churches took a long time, but eventually it was completed by the end of the century.

S. Benedetto: (left) courtyard and bell tower; (right) detail of a fresco depicting the saint appearing to a sick man in a dream and healing him

In 1997 another major earthquake struck Fabriano, Nocera and Camerino. The restoration of some monuments is still going on. You can see an image of the interior of S. Benedetto being restored in the introductory page.

The first canonizations by a Pope occurred in the Xth century. The process leading to proclaim a new saint evolved over time. Today, with the exclusion of martyrs for whom a special procedure exists, a good Roman Catholic who died from natural causes can be proclaimed saint if two miracles can be attributed to him. Usually the two miracles are related to individuals who recovered from a grave illness, without doctors being able to provide a scientific explanation. In the past however many saints were credited with miracles involving their intervention in support of one side in a battle, not necessarily between Christians and non-Christians (see the fresco below and

glass windows showing St. Ubald, patron saint of Gubbio, a nearby town in Umbria).

S. Domenico: fresco in the courtyard depicting a miracle occurred during a battle

The image used as background for this page shows a window of Palazzo del PodestÓ.

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini: detached XIVth century fresco from the Church of S. Domenico depicting the birth of St. John the Baptist

Move to:

Introductory page

Roman Ancona

Medieval Ancona

XVth Century Ancona

XVIth Century Ancona

Papal Ancona

Cingoli

Jesi

Loreto

Osimo

Recanati