All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in September 2024.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in September 2024.

Perugia - The Two Piazzas

Perugia - The Two PiazzasYou may wish to see a page on the history and fortifications of Perugia first.

Perugia, on its lofty hilltop, was reached by the two travellers before the sun had quite kissed away the early freshness of the morning. (..) They wandered to and fro and lost themselves among the strange, precipitate passages, which, in Perugia, are called streets, Some of them are like caverns, being arched all over, and plunging down abruptly towards an unknown darkness; which, when you have fathomed its depths, admits you to a daylight that you scarcely hoped to behold again. (..) Thence they climbed upward again, and came to the level plateau, on the summit of the hill, where are situated the grand piazza and the principal public edifices.

Nathaniel Hawthorne - The Marble Faun - 1860

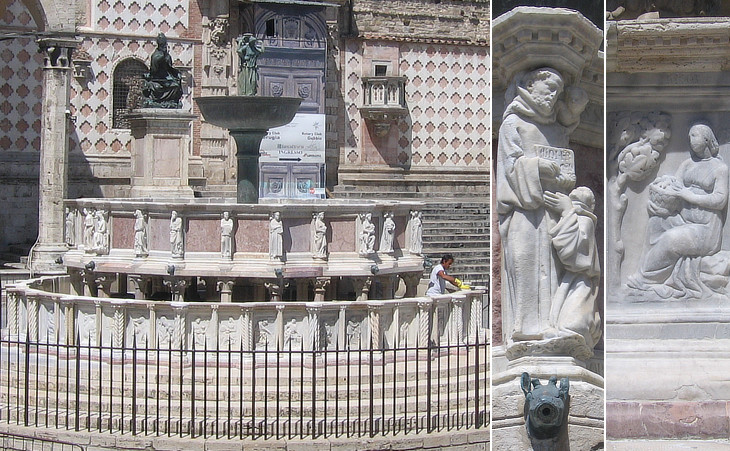

Fontana Maggiore: (left) overall view; (centre) a saint of the upper ring (St. Benedict); (right) a relief portraying a zodiacal sign/month in the lower ring (Virgo/August)

The citizens of the city-states which flourished in Northern and Central Italy after the year 1000

had often conflicting views on how their communities should be ruled. However they always agreed on one thing, regardless of their political opinions

and economic interests: they always supported the embellishment of their towns. A grand central piazza was often seen as the symbol of the importance acquired by a town. Fontana Maggiore was the first element of what was to become one of the finest Italian piazzas.

In the XIIIth century the town relied on the water taken from some ancient wells:

between 1254 and 1276 the municipal authorities built an aqueduct to provide

Perugia with an ample supply of fresh water and in 1275 they decided to celebrate its

completion by erecting a large fountain. Wells can still be seen in the neighbourhoods outside the Etruscan walls, e.g. Borgo S. Pietro.

Perugia commissioned the fountain to Nicola Pisano, who had acquired great fame as both an architect and a sculptor by his works in Pisa

(hence his "family name") and Siena.

He worked for three years with the assistance of his son Giovanni: the harmonious design of their fountain is an anticipation of the Renaissance

and the very rich decoration moves away from the traditional medieval iconography: it is worthwhile mentioning in detail the subjects of the reliefs and of the statues: the lower ring of the fountain is divided into 24 panels and each panel has two reliefs: a) panels 1-12 show the months of the year and the

corresponding zodiacal signs; b) panel 13 shows the symbols of Perugia: the Guelph lion and the griffin; c) panels 14-17 show the seven liberal arts and Philosophy; d) panel 18

is decorated with two eagles; e) panel 19 shows Adam and Eve and their banishment from Eden; f) panel 20 shows episodes of Samson's life; g) panel 21

is decorated with lions; g) panel 22 shows episodes of David's life; h) panel 23 shows episodes of the life of Romulus and Remus; i) panel 24 shows two fables by Aesop.

The upper ring was decorated with plain pink panels inserted in white frames,

a tribute to the local tradition of utilizing the

stone of Monte Subasio near Assisi; Giovanni Pisano placed between the panels 24 statues portraying saints, biblical and mythological characters and two members of Perugia's

government system: Matteo da Correggio, the acting podestÓ (a magistrate who ruled an Italian town in the XIIIth century;

usually he was a foreigner and held the position for only a short period) and Ermanno da Sassoferrato, the acting Capitano del Popolo, the leader of the representatives (Priori) of the municipal guilds.

This decoration shows the varied interests of an affluent and peaceful society.

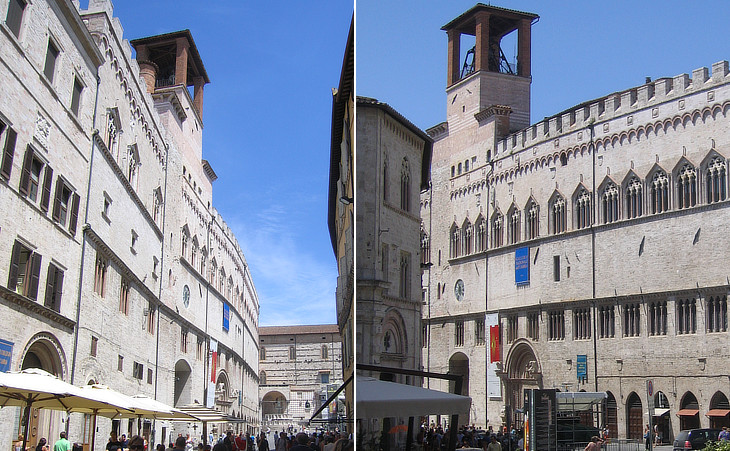

Palazzo dei Priori: (left) northern (oldest) front; (centre/right) details of the loggia

It happened to be market day in Perugia. The great square, therefore, presented a far more vivacious spectacle than would have been witnessed in it at any other time of the week, though not so lively as to overcome the gray solemnity of the architectural portion of the scene. In the shadow of the cathedral and other old Gothic structures - seeking shelter from the sunshine that fell across the rest of the piazza - was a crowd of people, engaged as buyers or sellers in the petty traffic of a country fair. Dealers had erected booths and stalls on the pavement, and overspread them with scanty awnings, beneath which they stood, vociferously crying their merchandise; such as shoes, hats and caps, yarn stockings, cheap jewelry and cutlery, books, chiefly little volumes of a religious Character, and a few French novels; toys, tinware, old iron, cloth, rosaries of beads, crucifixes, cakes, biscuits, sugar-plums, and innumerable little odds and ends, which we see no object in advertising. Baskets of grapes, figs, and pears stood on the ground. Donkeys, bearing panniers stuffed out with kitchen vegetables, and requiring an ample roadway, roughly shouldered aside the throng. Hawthorne

The piazza became known as Piazza della Fonte and only at a later time it was called Piazza del Duomo:

today the official name is Piazza IV Novembre 1918 (the day WWI ended in Italy).

Soon after the completion of the fountain the municipal authorities decided to build on the southern side of the piazza Palazzo dei Priori, a new town hall named after the magistrates who assisted Capitano del Popolo. On the right side of the fašade a balcony above an elegant loggia was used to make public announcements.

Palazzo dei Priori: views of its eastern front

Through all this petty tumult, which kept beguiling one's eyes and upper strata of thought, it was delightful to catch glimpses of the grand old architecture that stood around the square. The life of the flitting moment, existing in the antique shell of an age gone by, has a fascination which we do not find in either the past or present, taken by themselves. It might seem irreverent to make the gray cathedral and the tall, time-worn palaces echo back the exuberant vociferation of the market; but they did so, and caused the sound to assume a kind of poetic rhythm, and themselves looked only the more majestic for their condescension. On one side, there was an immense edifice devoted to public purposes, with an antique gallery, and a range of arched and stone-mullioned windows, running along its front; and by way of entrance it had a central Gothic arch, elaborately wreathed around with sculptured semicircles, within which the spectator was aware of a stately and impressive gloom. Hawthorne

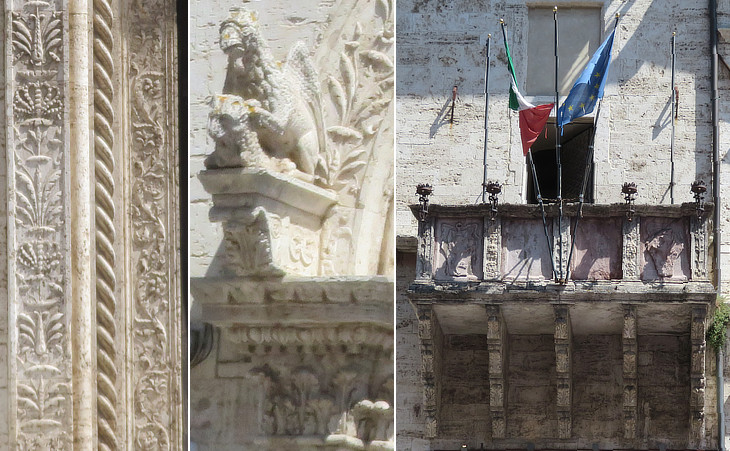

Palazzo dei Priori: eastern front portal and detail of its decoration

Though merely the municipal council-house and exchange of a decayed country town, this structure was worthy to have held in one portion of it the parliament hall of a nation, and in the other, the state apartments of its ruler. Hawthorne

Palazzo dei Priori has a fašade also along the main street of Perugia: this side of the palace was enlarged several times and in 1346 it was embellished by an elegant portal with a very complex decoration based on allegorical representations.

Palazzo dei Priori: (left) griffin on the eastern portal; (right) lion and griffin above the northern portal

The lion was the symbol of the Guelph party which supported the papacy: during the XIIIth century Perugia was very loyal to the popes and the cardinals often found it safer to hold their

conclaves in Perugia rather than in Rome: so popes Honorius III, Clement IV Honorius IV, Celestine V and Clement V were all elected in Perugia. For the same reason other conclaves were held in Viterbo. Pope Benedict XI died at Perugia where he is buried in a very elegant monument in S. Domenico.

The griffin, a mythical creature, is the symbol of Perugia and obviously it is seen on many buildings:

the statue of the griffin in the act of killing a calf was placed on the portal of Palazzo dei Priori by the butchers' guild of the town. Griffins were often depicted by the Romans on the short sides of sarcophagi and as a decorative motif on the entablatures of temples. In medieval churches occasionally griffins replaced lions as guardians of the building, e.g. at Verona.

Palazzo dei Priori - eastern front: (left) Collegio del Cambio (Guild of the Money-changers); (right) Collegio della Mercanzia (Guild of the Merchants)

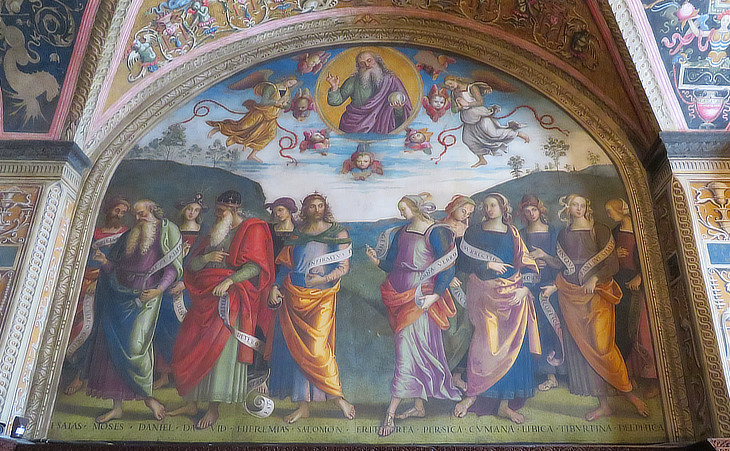

Pietro Vanucci, of Citta della Pieve, called Pietro Perugino, from the city of his adoption, is the great master of the Umbrian school. Perugino seems at first to have combined the styles of earlier painters with many peculiarities of the Florentine school; and at length, striking out into an original path, introduced that style, peculiarly his own, which exercised so great an influence on the earlier works of his pupil Raphael. (..) The Sala del Cambio (the Exchange), now no longer required for its original purpose, is covered with frescoes by Perugino, the best which he has left in the city of his adoption.

John Murray - Handbook for travellers in central Italy - 1843

In the Sala del Cambio, where in ancient days the money-changers rattled their embossed coin and figured up their profits, you may enjoy one of the serenest aesthetic pleasures that the golden age of art anywhere offers us.

Henry James - Italian Hours - 1874

Collegio del Cambio: frescoes by il Perugino (1496-1500)

On the left wall are different philosophers and warriors of antiquity, with allegorical figures of different virtues above them. They occur in the following order: Lucullus, Leonidas, Cocles, with the figure of Temperance; Camillus, Pittacus, Trajan, with the figure of Justice; Fabius Maximus, Socrates, and Numa Pompilius, with the figure of Prudence. On the wall opposite the entrance are the Nativity and Transfiguration. (..) On the roof, amidst a profusion of beautiful arabesques, are the deities representing the seven planets, with Apollo in the centre. Murray

The bravery is of Perugino; for, invited clearly to do his best, he left it as a lesson to the ages, covering the four low walls and the vault with scriptural and mythological figures of extraordinary beauty. They are ranged in artless attitudes round the upper half of the room - the sibyls, the prophets, the philosophers, the Greek and Roman heroes - looking down with broad serene faces, with small mild eyes and sweet mouths that commit them to nothing in particular unless to being comfortably and charmingly alive, at the incongruous proceedings of a Board of Brokers. James

You may wish to see two small paintings by Perugino at Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini.

730>

730>Collegio del Cambio: fresco by il Perugino portraying Prophets and Sibyls (you may wish to see the Sibyls whom Raphael painted at S. Maria della Pace in Rome)

On entering the hall, the paintings on the right wall are the Erythrean, Persian, Cumean, Lybian, Tiburtine, and Delphic sibyls; the Prophets Isaiah, Moses, Daniel, David, Jeremiah, and Solomon; and above, the Almighty in glory. (..) In the execution of these graceful frescoes Perugino was assisted by Raphael; the Erythrean and Lybian sibyls, and the head of the Saviour in the Transfiguration, are said to be his works (today Daniel is thought to be a portrait of Raphael and the head of Solomon another work by him). Murray

He may very well have wanted to produce figures of a substantial, yet at the same time of an impeccable innocence; but we feel that he had taught himself how even beyond his own belief in them, and had arrived at a process that acted at last mechanically. I confess at the same time that, so interpreted, the painter affects me as hardly less interesting, and one can't but become conscious of one's style when one's style has become, as it were, so conscious of one's, or at least of its own, fortune. If he was the inventor of a remarkably calculable facture, a calculation that never fails is in its way a grace of the first order, and there are things in this special appearance of perfection of practice that make him the forerunner of a mighty and more modern race. More than any of the early painters who strongly charm, you may take all his measure from a single specimen. The other samples infallibly match, reproduce unerringly the one type he had mastered, but which had the good fortune to be adorably fair, to seem to have dawned on a vision unsullied by the shadows of earth. Which truth, moreover, leaves Perugino all delightful as composer and draughtsman; he has in each of these characters a sort of spacious neatness which suggests that the whole conception has been washed clean by some spiritual chemistry the last thing before reaching the canvas; after which it has been applied to that surface with a rare economy of time and means. James

You may wish to see the much more dramatic frescoes by Piero Della Francesca at Arezzo (1452-1458).

Collegio della Mercanzia: wooden decoration of the meeting hall (second half of the XVth century)

Similar to what occurred in most medieval Italian towns, including Rome, economic activities were organized through guilds. The most important guilds of Perugia had their premises in Palazzo dei Priori. The merchants decorated their meeting hall with elaborate hand carved wooden panels depicting Gothic architectural elements. The griffin of Perugia stands on a bale, the symbol of the guild. You may wish to see the wooden decoration of S. Pietro de' Cassinesi.

Cathedral (S. Lorenzo) - eastern side: (left) unfinished fašade; (right) XVIIIth century portal with two ancient granite columns

On another side of the square rose the mediaeval front of the cathedral, where the imagination of a Gothic architect had long ago flowered out indestructibly, in the first place, a grand design, and then covering it with such abundant detail of ornament, that the magnitude of the work seemed less a miracle than its minuteness. (..) In fit keeping with all this old magnificence was a great marble fountain, where again the Gothic imagination showed its overflow and gratuity of device in the manifold sculptures which it lavished as freely as the water did its shifting shapes. Hawthorne

A church closed the piazza on its northern side, but the inhabitants of Perugia felt its size and decoration

was no longer appropriate for their town. The decision to build a new cathedral was taken at the beginning of the XIVth century, but work started only in 1345, just a few years before the fortunes of Perugia started to decline: in 1348 the pestilence known as the Black Death greatly reduced its

population and a few years later Cardinal Gil de Albornoz restored papal authority in the region.

Cathedral - southern side: (left) 1568 portal by Ippolito Scalza, an architect from Orvieto; (centre) pulpit; (right) decorative motif (also in the image used as background for this page) and two small niches

Although Perugia maintained many of its privileges and some sort of self-government it could not devote to the construction of the cathedral the resources required by the initial ambitious plan. The building was not completed until 1490 and the elegant white and pink facing covered only part of the southern side which was also embellished by a very fine pulpit with a Cosmati work decoration.

Cathedral - interior: (left) Baptistery chapel: 1479 marble frame; (right) Cappella dell'Anello in the left aisle: detail of a 1529 wooden inlay by Giovanni Battista Bancone which is based on grotesques

The decoration of the interior was unfinished, or rather it was completed in the XIXth century. Evidence of Renaissance works of art can be seen in some chapels, but in general the interior is rather bare and gives a feeling of emptiness.

Cathedral - interior: (left) ceiling of a side aisle with frescoes of the late XVIIIth century; (right) Cappella di S. Bernardino in the right aisle which belonged to the guild of the merchants: Descent from the Cross by Federico Barocci (1569), a painter from Urbino

The two aisles have the same height of the nave, a characteristic of German Hallenkirche which departs from the design of a traditional basilica. The Cathedral does not have the usual series of family chapels, but some of them were placed in the nave or the aisles, similar to the chantries of Gothic cathedrals, e.g. that of Winchester.

Bronze statue of

Pope Julius III by Vincenzo Danti (1555)

Besides the two venerable structures which we have described, there were lofty palaces, perhaps of as old a date, rising story above Story, and adorned with balconies, whence, hundreds of years ago, the princely occupants had been accustomed to gaze down at the sports, business, and popular assemblages of the piazza. And, beyond all question, they thus witnessed the erection of a bronze statue, which, three centuries since, was placed on the pedestal that it still occupies.

"I never come to Perugia," said Kenyon, "without spending as much time as I can spare in studying yonder statue of Pope Julius the Third. Those sculptors of the Middle Age have fitter lessons for the professors of my art than we can find in the Grecian masterpieces. They belong to our Christian civilization; and, being earnest works, they always express something which we do not get from the antique. Will you look at it?" (..) They made their way through the throng of the market place, and approached close to the iron railing that protected the pedestal of the statue.

It was the figure of a pope, arrayed in his pontifical robes, and crowned with the tiara. He sat in a bronze chair, elevated high above the pavement, and seemed to take kindly yet authoritative cognizance of the busy scene which was at that moment passing before his eye. His right hand was raised and spread abroad, as if in the act of shedding forth a benediction, which every man-so broad, so wise, and so serenely affectionate was the bronze pope's regard - might hope to feel quietly descending upon the need, or the distress, that he had closest at his heart. The statue had life and observation in it, as well as patriarchal majesty. An imaginative spectator could not but be impressed with the idea that this benignly awful representative of divine and human authority might rise from his brazen chair, should any great public exigency demand his interposition, and encourage or restrain the people by his gesture, or even by prophetic utterances worthy of so grand a presence.

And in the long, calm intervals, amid the quiet lapse of ages, the pontiff watched the daily turmoil around his seat, listening with majestic patience to the market cries, and all the petty uproar that awoke the echoes of the stately old piazza. He was the enduring friend of these men, and of their forefathers and children, the familiar face of generations.

"The pope's blessing, methinks, has fallen upon you," observed the sculptor, looking at his friend. (..) "Yes, my dear friend," said he, in reply to the sculptor's remark, "I feel the blessing upon my spirit."

"It is wonderful," said Kenyon, with a smile, "wonderful and delightful to think how long a good man's beneficence may be potent, even after his death. How great, then, must have been the efficacy of this excellent pontiff's blessing while he was alive!" Hawthorne

The bronze statue by Danti became a model for other statues of popes, e.g. Sixtus V, Paul V and Innocent X.

Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo

A short street leads from Piazza IV Novembre to another very interesting square (today it is called Piazza Matteotti) which was mainly developed during the XVth century: the role of the Capitano del Popolo at that time was that of a magistrate and the palace built in 1473-1481 was used to house some of the tribunals: legislation was very complex for the overlapping of state, municipal and religious jurisdictions and so there were several different judicial institutions. The statue above the entrance portrays Justice holding a sword.

Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo: (left/centre) details of the portal; (right) balcony for announcements

The history of Perugia in the middle ages is not less interesting than that of Florence or Siena, although the struggles of this free city against the growing power of the popes, and the contests which followed between the popular party and the nobles, differ little from those which were the immediate precursors of the fall of nearly all the Italian republics. Murray

Palazzo dell'UniversitÓ Vecchia

The ancient name of the piazza was sopramuro (above the wall) which derives from the subterranean masonry by which it is supported. Its eastern side stood on the edge of the artificial terrace: it was the site of several markets and the very long palace shown above was initially built (mid XVth century) to obtain a series of shops. Pope Sixtus IV commissioned the construction above the shops of facilities for the local university and other institutions.

Palazzo dell'UniversitÓ Vecchia: windows and coat of arms with the letters O. M. (Ospedale della Misericordia); the inscription above the windows is a long quotation from Matthew (25: 35/36)

The windows are similar to those of Palazzo Venezia in Rome. The building housed the university until 1811 and then it became a public library containing interesting manuscripts and a collection of XVth century books published in Perugia.

You may wish to see the two main piazzas of Ascoli, another historical town of the Papal State.

Move to Walls and Gates, The Papal Street (Borgo S. Pietro), S. Pietro de' Cassinesi, The Tomb of the Volumni, The Archaeological Museum or wander about to see other churches, palaces and fountains.