All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in December 2020.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in December 2020.

- Rimini

- Rimini

Arco di Augusto at the Via Flaminia entrance to the town

The gate under which the traveller passes on his way to Pesaro, is a triumphal arch of Augustus, of the best materials and noblest form. The order is Corinthian, but in some respects peculiar. The barbarous taste of the middle ages crowned this monument of Roman grandeur with a Gothic battlement, a deformity which is still allowed to exist, "in media luce Italiae" in such an age and in such a country.

John Chetwode Eustace - A Classical Tour through Italy in 1802

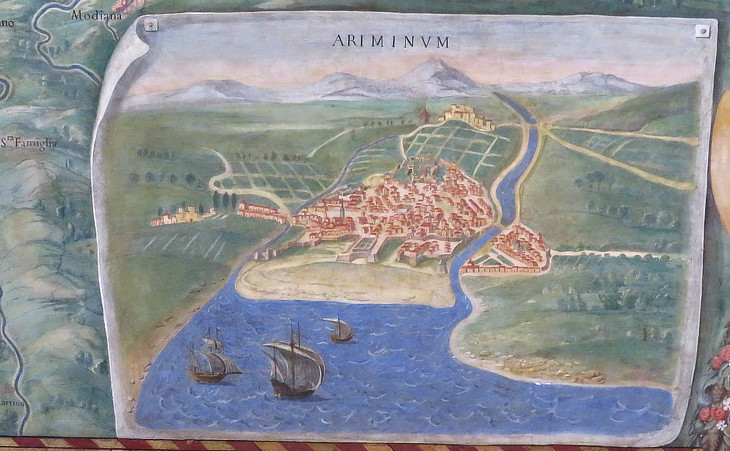

In 268 BC the Romans founded Ariminum, a town at the mouth of the River Marecchia, a small stream which traditionally marks the geographic border between Northern Italy and the peninsula. It was a strategic outpost for the expansion into Gallia, the name the Romans gave to a vast territory which included France, Belgium and parts of Switzerland in addition to Northern Italy.

In 220 BC Rome was linked to Ariminum by Via Flaminia, a road which crossed Umbria and the Apennines and reached the Adriatic Sea at Fanum (Fano). It then bordered that sea and ended at Ariminum.

Upper section of the arch which retains part of the commemorative inscription

In the Ist century BC Ariminum acquired a particular importance because the border between the territory of the Roman Republic (peninsular Italy) and the province of Cisalpine Gaul was set on the Rubicon, a small stream a few miles west of the town. In 49 BC Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon and entered Ariminum, the first step of a victorious campaign which made him the sole ruler of the Republic.

In 27 BC an arch dedicated to Emperor Augustus was built at the Via Flaminia entrance to town. It celebrated improvements to that road, which were so expensive that Augustus quoted them (viam Flaminiam a[b urbe] Ari[minum] refeci) in Res Gestarum Divi Augusti, the summary of his achievements he dictated at the age of 77. The arch was not meant to be a defensive gate (it was too wide),

but eventually it was flanked by towers. Merlons were built on its upper part in the Xth century.

(left) Detail of the arch showing a cross in the capital and a head of Jupiter; (right) Roman gate on the road leading to the Apennines

Arco di Augusto became (and still is) the symbol of the town. The four medallions framing heads of gods were not damaged when the inhabitants of Ariminum became Christians. The arch was the starting point of the main street of the town which ended on the shore of the River Marecchia, the mouth of which was used as a harbour.

Ariminum was the ending point of another (minor) Roman road which linked the town to Arretium (Arezzo) in Tuscany across the Apennines.

(above) Ponte di Tiberio; (below) parts of the celebratory inscription

The bridge, over which we passed, is of marble, and in the best style of Roman architecture, erected in the times of Augustus and Tiberius Caesar, and inscribed with their names. It consists of five arches with niches for statues between, and a regular cornice surmounting both arches and niches. Its solidity, boldness and beauty, as well as the date of its erection, have led many connoisseurs to conclude, that it is the work of Vitruvius. Eustace

In 189-187 BC the Romans built Via Aemilia, a road which crossed the region to the north of the Apennines in a straight line from Ariminum to Placentia (Piacenza)

on the River Po (Roman roads were usually named after the consuls who built them). The road eventually gave its name to the region it crossed. Emperor Augustus promoted the construction of an imposing bridge

across the River Marecchia which marked the starting point of Via Aemilia. The bridge was completed by Emperor Tiberius, Augustus' successor and it is still being used (not just by pedestrians).

Ponte di Tiberio: central arch

The River Marecchia is only forty miles long and its discharge is very low, except in Autumn. The bridge could have been made much shorter by redesigning the banks of the Marecchia, but its size and decoration were meant to impress. The construction of imposing public facilities (including baths and amphitheatres) was part of a policy aimed at showing provincial towns the benefits of being part of the Roman Empire.

Ruins of the amphitheatre

In 1989 a Roman house was discovered in the centre of the town and in 2007 the area was open to the public as part of the Civic Museum.

You may wish to see a page with some background information on this section and medieval Rimini first.

Palazzo dell'Arengo

Many have heard about Rimini as a seaside resort with more than 1,000 hotels and guesthouses, but the railway line separates the "Rimini which never sleeps" with its pubs and discos, from the historical town which retains several interesting monuments in addition to those shown in the foreword.

In the XIth century Rimini became a Comune, an almost independent city-state, although formally belonging to the Papal State. The town, as many other Italian Comuni, was ruled by a complex system of government where key decisions had to be discussed in a general assembly (arengo) of the representatives of guilds,

neighbourhoods and other social groupings. These meetings took place in open spaces as in Ascoli or in large halls as in Rimini. Palazzo dell'Arengo was built at the beginning of the XIIIth century, but it was modified several times, yet overall it retains its medieval appearance. It stands in a large square adjoining the main street of the town which in summer houses a very busy market.

Castel Sismondo: (left) main entrance; (right) inscriptions "Sigismondo Malatesta" and coats of arms

Quarrels among the inhabitants of the Italian city-states were quite common and eventually led to calling in a foreigner (podestÓ from Latin potestas, authority) to rule the town for a limited period of time, usually six months or one year. In 1239 a member of the Malatesta family from Verucchio, a small castle south of Rimini, was appointed podestÓ of Rimini. It was the beginning of a period which lasted three centuries during which the Malatesta acted as de facto rulers of the town, seeking the support of the German Emperors or of the Popes to justify the legitimacy of their power. Other towns, e.g. Cesena, Fano, Senigallia and Ascoli, fell into their sphere of influence.

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, who ruled Rimini between 1432 and 1468, was regarded as one of the most valiant condottieri of his time. He did not lack self-esteem and the residence-castle he built on the site of previous fortifications and houses of his family, was decorated with inscriptions bearing his name and his heraldic symbols, which included an elephant as he claimed the Malatesta were descended from Scipio Africanus, the Roman general who defeated Hannibal.

In another inscription he explicitly wrote that the building should be called Castel Sismondo, a shortened version of Sigismondo, his name. The castle was surrounded by a moat and by walls and it was completed in 1451. Its design did not include some of the features which were introduced in Italian fortresses (as in nearby San Leo) in the second half of the century to cope with the development of cannon.

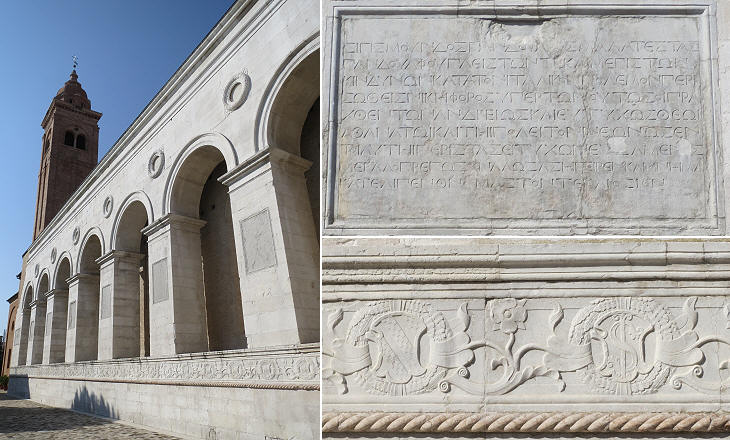

Tempio Malatestiano: (left) eastern side; (right-above) Greek inscription (translated by Luigi Orsini as "To immortal God - Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta of Pandolfo - preserved victorious from many

and great perils in the Italic wars for the enterprises

so happily achieved - to immortal God and to the city -

as he in battle vowed - erected with lavish hand this

temple and left it as a famous and holy memorial"); (right-below) detail of the frieze which runs on the sides and the fašade of the building and depicts the coat of arms and heraldic symbols of Sigismondo Malatesta and the monogram S/I (Sigismondo and Isotta)

In 1447 Sigismondo Malatesta decided to build two new chapels on the sides of a church dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi where he and Isotta degli Atti, his third wife and lifetime mistress would be buried. Eventually he decided to rebuild the whole church as a funerary chapel for all Malatesta and members of their court. He entrusted the design of the new building to Leon Battista Alberti, a Florentine architect, but actually a man of many varied interests and the author of treatises on painting, sculpture and architecture.

Both sides of the new building were flanked by a portico decorated with wreaths similar to the central arch of Ponte di Tiberio. Members of the court were expected to be buried under these arches (seven of them are actually buried in the western portico).

Tempio Malatestiano: fašade

The church of St. Francis, adorned with a profusion of marble, deserves notice, particularly as it is supposed to be the last in Italy, if we except however the cathedral of Milan, into which Gothic forms and ornaments have been admitted. In fact, it was built in the year 1450, a period when the latter style began to give way to the restored proportions of Roman architecture. However, this attempt to resume the graces of antiquity does not seem to have succeeded, as the orders are ill proportioned and the whole edifice clumsy and whimsical. Eustace

Alberti found inspiration in Arco di Augusto for the design of the fašade which so much departs from traditional ones that the building is known as Tempio, even after it became the Cathedral of Rimini in 1809.

The fašade was never completed because the fortunes of Sigismondo Malatesta declined after 1462.

Tempio Malatestiano: Monument to the Ancestors of Sigismondo Malatesta

Sigismondo Malatesta built a funerary monument to his father in S. Francesco in Fano, but he decided to dedicate to him and to all his other ancestors the first chapel of the new building. It is actually a monument to himself, as he was portrayed in medallions in the lower part of the monument and in one of the reliefs of the sarcophagus. Art historians believe the latter was initially meant to be placed in a niche of the fašade because its not visible side is decorated too.

Tempio Malatestiano: (left) interior; (centre/right) details of the chapel where Isotta degli Atti is buried

Many of the reliefs which decorate the building were made by Agostino di Duccio, a Florentine sculptor, scholar of Donatello, from whom he learned the technique known as stiacciato (flattened), a very low relief. He employed this technique in many reliefs of Tempio Malatestiano, including those portraying angels playing musical instruments (two of which are used as background image for the Hall of Fame page of this website). The image used as background for this page shows another relief by Agostino di Duccio which depicts Cancer, the zodiacal sign of Sigismondo Malatesta. You may wish to see other reliefs he made in S. Bernardino in Perugia.

Tempio Malatestiano: (left) detail of Cappella di S. Girolamo; (centre/right) reliefs on the door leading to a separate chapel portraying David (left) and Samson (right)

The cause of the decline of the fortunes of Sigismondo Malatesta was his confrontation with Pope Pius II who launched a sort of crusade against him after having condemned him to Hell in a trial in Rome. The curse of the Pope fell on the church he was building too which was defined as too full of pagan things to be regarded as a church.

In 1462 Sigismondo was defeated by Federico da Montefeltro near Senigallia and was forced to ask for the papal pardon which he obtained on the condition that he relinquish all his possessions outside Rimini.

He was eventually buried in his church, but in a rather plain sarcophagus to the side of the entrance and not in one of the elaborate chapels.

Rimini in a late XVIth century fresco in Galleria delle Mappe Geografiche in the corridors of Palazzo del Belvedere in Rome

At the end of the XVth century the Malatesta were ousted from Rimini by Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI. The town, after a short period during which it was controlled by the Venetians, returned under the direct rule of the Papal State.

(left) Fontana della Pigna; (right) detail showing the papal symbols. You may wish to see the heraldic symbols of Pope Paul III in a page on the "Papal Coats of Arms Spared by the Revolution"

In 1543 a medieval fountain in the main square was redesigned and decorated with papal symbols. It was known as Fontana di S. Paolo, because of a statue of St. Paul which was replaced by a fir-cone (pigna) in the XIXth century.

(left) Monument to Pope Paul V; (right) Tempietto di S. Antonio

In the principal square is a fountain, and a statue of Paul V., changed into that of St. Gaudentius by the French, who, upon this occasion, seem, I know not how, to have forgotten their usual propensity to destruction. Eustace

In 1614 a bronze statue of Pope Paul V was erected near Fontana della Pigna. It was made locally by Sebastiano Sebastiani, but it was based on a sketch by Nicolas Cordier, a French sculptor in Rome whom the Pope had given many commissions including that for a bust of Jesus in S. Agnese fuori le Mura. In 1797, during the French occupation of Rimini, the dedicatory inscription was modified and the pope's crown was covered with a mitre; the statue was then supposed to portray Gaudentius of Rimini, the patron saint of the town.

Rimini, as all the towns of the Papal State had a large number of churches some of which were destroyed during WWII or were pulled down to make room for modern buildings. Tempietto di S. Andrea stands out from the other churches for its marble facing and its elegant design (XVIth century with alterations made in the XVIIIth century).

Move to:

Introductory page

Cagli

Cesena

Fano

Fossombrone

Gradara

Macerata Feltria

Pesaro

San Leo

Sassocorvaro

Senigallia

Urbania

Urbino