All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in October 2022.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in October 2022.

Etruscan and Roman Arezzo

Etruscan and Roman ArezzoIf you came to this page directly, you might wish to read a page with an introduction to this section and a map of Val di Chiana first.

View towards Casentino, the Upper River Arno valley, from Via di S. Domenico

Descending the hill of Arezzo next morning to

the Etrurian plains, so famed at all times for their

fertility, and shortly after passing the Chiana or

Clanis which intersects them, we entered the Val

d'Arno, the Italian Arcadia.

J. C. Eustace - Classical Tour of Italy in 1802 (publ. 1813)

It is not for me to set forth the modern glories of Arezzo - her Cathedral with its choice monuments of sculpture and painting - the quaint-fashioned church of La Pieve - the localities immortalised by Boccaccio - the delightful promenade on her ramparts - the produce of her vineyards. (..) This large and lively city is the representative of the ancient Arretium or Aretium, a venerable city of Etruria, and one of the Twelve of the Confederation. (..) Of the origin of Arretium we have no record. The earliest notice of it is, that with Clusium, Volaterrae, Ruselle, and Vetulonia, it engaged to assist the Latins against Tarquinius Priscus. We next hear of it in the year 443 (B.C. 311) as refraining from joining the rest of the Etruscan cities in their attack on Sutrium, then an ally of Rome; yet it must have been drawn into the war, for in the following year, it is said, jointly with Perusia and Cortona, all three among the chief cities of Etruria, to have sought and obtained a truce for thirty years. (..) The last mention we find of Arretium, in the time of national independence, is that it was besieged by the Gauls about the year 469, and that the Romans, vainly endeavouring to relieve it, met with a signal defeat under its walls. There is no record of the date or the manner of its final conquest by Rome.

George Dennis - The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria - 1848

(left) Piazza Guido Monaco, a circular square on the way from the railway station to the town and the Cathedral with its XIXth century bell tower in the background; (right) plaque on the house of Guido Monaco in Via Cesalpino near S. Francesco

This city is famous for the birth of Guido, the Benedictin monk, who invented the musical notes, ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la.

Thomas Nugent - The Grand Tour - 1749

Though Arezzo can scarcely rank Petrarca among

her sons, she can boast of many an illustrious name,

and display a long list of worthies distinguished in

arts and in arms. Among these I shall only mention one, because though his merit was great, yet

his profession was humble, and his name obscure.

Guido Aretino, a monk of the eleventh century,

invented the scale of notes now in use, and thus

gave to music, as writing does to language, a form

and a body, which may preserve and convey its

accents down to the latest posterity. Eustace

From the excavations made at various periods within and around the walls of Arezzo, it is pretty evident that the Etruscan necropolis, though not the Etruscan city, occupied the site of the modern town. On the low ground, near the railway station to the left of the circular Piazza, which you cross on the way from the station to the town, numerous Etruscan tombs have been found, which have yielded pots of black bucchero, together with some painted vases, and little figures and mirrors in bronze. Dennis

Before the Etruscan necropolis was found the fame of Arezzo as an ancient town was based on two large bronze statues which were discovered in the XVIth century when digging for the construction of new walls. Most likely they had been buried in the ground on purpose. They were moved to Florence and today they are in its Archaeological Museum.

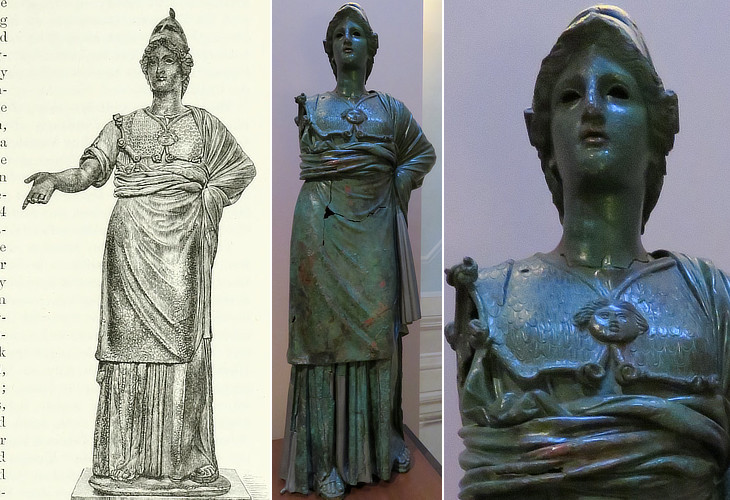

Minerva: (left) illustration from Dennis' book; (centre/right) the statue at the Museum of Florence

Sixth Room. - Here stands the celebrated statue of Minerva, found at Arezzo, in 1554. She is represented nearly of life-size, with her right hand and arm extended as in the act of haranguing. Her left arm, wrapt in her drapery, rests on her hip. The neck of the statue has suffered much from corrosion; the face also in a less degree. The sockets of the eye's, are empty, and were probably filled with gems. Her imation which hangs over her left shoulder, and is drawn tightly across her body in front, contrasts with the many small folds of her chiton, which reaches to her feet. Her helmet is crested with a serpent, an Etruscan feature. Yet the pose of the figure is Greek rather than Etruscan, showing great ease and dignity combined. If the statue be really from an Etruscan chisel, it betrays the influence of Greek art in no small degree. Dennis 1878 edition

In 1785 the right arm was added to the original statue and the position of the head was modified. In 2009 the statue was brought back to the aspect it had before 1785. It is likely that Minerva held a spear, similar to the Athena Giustiniani and other ancient statues of the goddess.

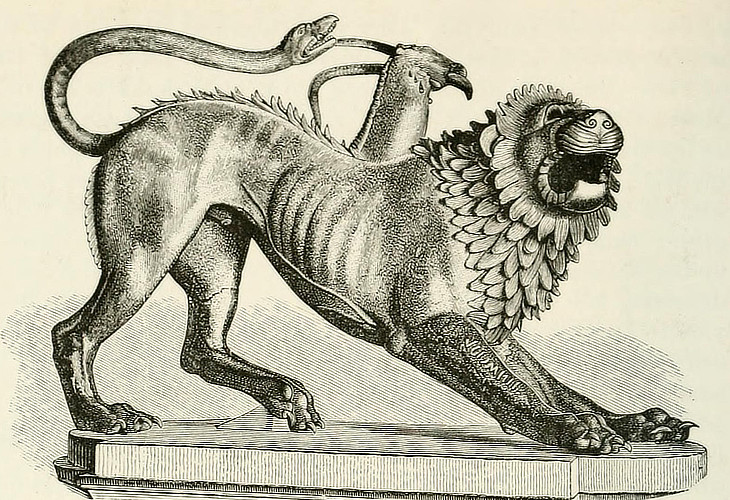

Chimera (illustration from Dennis' book, see the original and learn about this monster)

Sculpture was in great esteem and in no small perfection among the Etruscans; but what clearer proof of this can be sought seeing that in our own day - that is, in the year 1554 - there has been found a bronze figure of the Chimaera of Bellerophon, in making the ditches, fortifications, and walls of Arezzo, from which figure it is recognized that the perfection of that art existed in ancient times among the Etruscans, as may be seen from the Etruscan manner and still more from the letters carved on a paw, about which - since they are but few and there is no one now who understands the Etruscan tongue - it is conjectured that they may represent the name of the master as well as that of the figure itself, and perchance also the date, according to the use of those times. This figure, by reason of its beauty and antiquity, has been placed in our day by the Lord Duke Cosimo in the hall of the new rooms in his Palace.

Giorgio Vasari - Lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors & architects - transl. by Gaston Du C. De Vere

In the centre of the Seventh Room stands the Chimera, a celebrated work in bronze, discovered at Arezzo in 1554, at the same time as the Minerva. It has the body of a lion, a goat's head springing from its back, and a serpent for a tail - the latter, however, is a modern restoration. The figure is full of expression. The goat's head, pierced through the neck, is already dying, and the rest of the creature is writhing in agony from this and another wound it has received from the spear of Bellerophon. The style of art much resembles that of the celebrated Wolf of the Capitol, but is less archaic; and its origin is determined by the word "Tixskvil" in Etruscan characters carved on the right foreleg. Dennis 1878 edition

The Etruscans used to carve the name of their gods or heroes on the legs/paws of statues dedicated to them, e.g. those to Selvans and Culsans at Cortona.

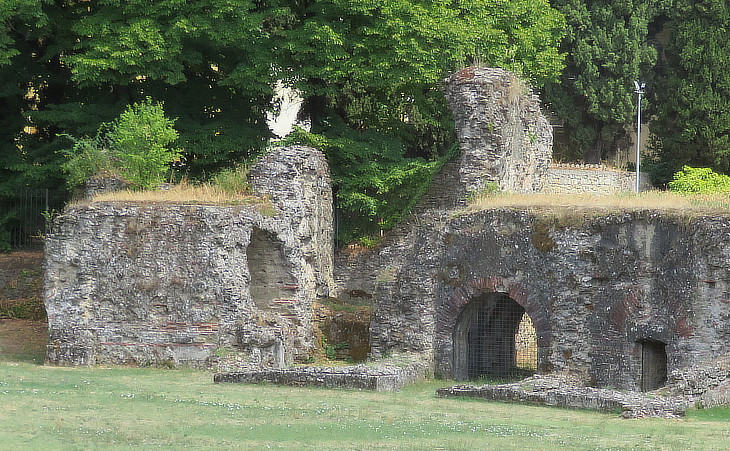

Amphitheatre (see the Colosseum and a list of other Roman amphitheatres shown in this website)

Arretium is one of the ancient Etrurian cities,

though, with the exception of the supposed substructions of an amphitheatre, it can boast of no

vestige of its former celebrity. Eustace

In the garden of the Passionist Convent, in the lower part of the town, are some Roman ruins, of opus reticulatum, commonly called the Amphitheatre, but not a seat remains in the cavea to indicate that such was the purpose of the structure. (..) This building was long considered to be Etruscan, but its Roman origin is most manifest. Dennis

Amphitheatre seen from Museo Archeologico Nazionale Gaio Clinio Mecenate

The Museo Pubblico contains a numerous collection of Etruscan antiquities. An article is labelled with the name of the spot where it was found - an admirable plan, greatly facilitating an acquaintance with these relics, and which ought to be adopted in every other collection. It is due to Dr. Fabroni, the learned director of this Museum. (..) Some of Arezzo children's names have filled the trump, not of Tuscan, but of universal fame; and the city has produced a Maecenas and a Petrarch. Dennis

The Public Museum was founded in 1823 inside Confraternitą di S. Maria della Misericordia. In 1936 it was moved to a new location in the former convent near the amphitheatre and it was dedicated to Maecenas.

Museum: Bronzes from a "Lararium": (left) two dancers wearing a basket on their heads; (right) Jupiter

The first room contains the bronzes. Here are numerous little figures of deities of all descriptions, but principally Lares and Genii, many Etruscan, some Roman; mirrors with mythological subjects, paterae with figured handles, strigils, fibulae, flesh-hooks, sacrificial knives, coins, and a variety of objects in the same metal. Dennis

Some small bronze

statues dating back to the Ist century BC were found in the

Lararium of a rich aristocratic house. The Lararia were

small shrines or niches where the images of the

patron gods of the household and of the family were placed. Their cult was carried out in the house by

the pater familias (see Lararia at Ostia and Pompeii). The dancers wear a wicker basket full of fruit and flowers, similar to the canephorae, a type of caryatids.

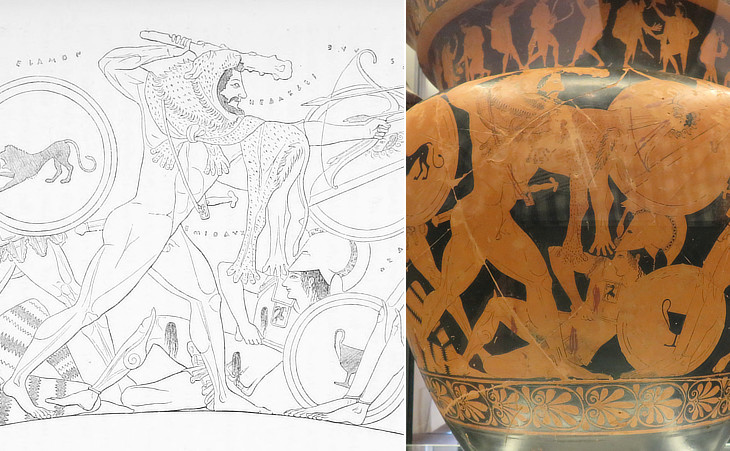

Vase depicting Hercules fighting the Amazons in an illustration of Dennis' book and the actual one

Second Room. Pottery. On a stand in the centre of this room is a vase of wonderful beauty. It is a krater of large size, with handles rising above the rim. Hercules is here represented combating the Amazons. In the centre the son of Alcmena, with his lion-skin over his head, and wrapt round his left arm, holds out his bow and arrow with the same hand, while he strikes with uplifted club at the three Amazons before him. (..) The demi-god has already vanquished one of his fair foes, who having received three fearful wounds apparently from his sword, which he has returned to its sheath, is sinking to the ground at his feet. The shield on her arm displays a kantharus as its device, and on her cuirass is the figure of a small lion. Dennis

Museum: Cinerary urn with a relief portraying two female demons

The Third Room contains Etruscan sepulchral urns of travertine, alabaster, or marble, mixed with Roman cinerary urns of stone with Latin inscriptions. Most of the Etruscan urns are without recumbent figures, but all bear inscriptions. In a case in this room are displayed a few urns of terra-cotta, bearing the usual subjects of the Theban Brothers (Polynices and Eteocles), Cadmus, &c. One, however, shows an arched doorway, the gate of Orcus (the Underworld), on each side of which a winged Fury, with torch and buskins, sits upon a rock, in an attitude of expectation; one of them having just extinguished her torch. These demons have occasionally neither wings, buskins, nor anything, but the attributes in their hands to distinguish them from ordinary mortals (see a fresco in a tomb at Tarquinia). Here are some portrait-heads in the same material; and numerous little figures of babies, votive offerings, all from the same mould. Dennis

Museum: "Terra Sigillata" (ware with the maker's seal); see similar ware which was exported to Britain

The red and black vases of Arezzo, were made, as may be judged from the manner, about those times, with the most delicate carvings and small figures and scenes in low-relief. Vasari

In the war between Caesar and Pompey, Arretium was one of the first places seized by the former. Her fertile lands were three times partitioned among the soldiers of the Republic, and the colonies established were distinguished by the names of Arretium Vetus, Fidens, and Julium. (..) Arrretium was celebrated of old for her pottery, which was of red ware. Pliny (..) says it was used for dry meats as well as for liquids, and was sent to various parts of the world. It was much employed for ordinary purposes. (..)

In excavations made at various times within the walls of Arezzo, generally in laying the foundations of buildings, much of this pottery has been brought to light; in one place, indeed, the site of a factory was clearly indicated. This ware is of very fine clay, of a bright coral hue, adorned with reliefs, rather of flowers than of figures, and bearing the maker's name at the bottom of the vase. In form, material, decoration, and style of art, it is so totally unlike the produce of any Etruscan necropolis, that it scarcely needs the Latin inscriptions to mark its origin. Dennis

The maker's name or brand was usually stamped on Roman bricks.

Museum: terracotta panels which decorated a temple

The sima, the uppermost part of the cornice of an Etruscan temple, was composed of adjacent terracotta slabs (see an example in Rome). The panels shown above were decorated with fighting scenes in high relief (480 BC). These architectonical elements, together with antefixes and other decorative elements were found in 1948 in a dump near Corso Italia. They belonged to a single sacred complex, of which the original location is unknown. You may wish to see the large terracotta statues which decorated a temple of Veii.

Museum: terracotta sculptures (ca IInd century BC): (left) head of a man with a Phrygian cap; (centre) two crossed feet in sandals (see a page on this topic); (right) head of a young man with a "taenia", a headband, typical of Greek statuary (see the Charioteer and the Diadumenos)

Some terracotta statues of high artistic level were found immediately outside the medieval walls of Arezzo. They show the influence of Greek models, but also the realism which characterized Roman portrait sculpture.

Museum: (left) marble statue; (right) part of a circular funerary monument

In 1994 marble fragments of a funerary monument resembling a temple (most likely similar to some tombs of Pompeii) were found along an ancient road immediately outside Arezzo. With some surprise the archaeologists discovered an imposing marble statue representing a standing male

figure wearing a tunic and toga. The statue had

been purposely buried in an oblique position. The head is characterized by

realistic features. Wrinkles on the face recall an older person, probably an important public figure as the presence of the

capsa, a round container of scrolls (see it better in a Roman mosaic) suggests. We do not know his name. The statue is dated late Ist century BC.

A circular

funerary monument was discovered in the XVIIIth century at Monte Petrognano, north of Arezzo. It retained the decorated inscription which was placed on the monument by a member of the gens Petronia which explains the name of the location. The inscription is very similar to that of Mausoleo di Lucilio Peto in Rome.

Museum: detail of a Roman floor mosaic (IInd century AD)

In 1933 fragments of a Roman floor mosaic were found inside the medieval walls of Arezzo. Their subject, Neptune holding a trident and driving a quadriga of seahorses, suggests that they decorated one of the halls of a bath establishment, similar to what can be seen at Ostia and Herculaneum.

The image used as background for this page shows part of an opus sectile (marble inlay) decoration which was found near the mosaic.

Museum: Longobard jewels (VIth century AD)

Arezzo was almost destroyed by the

Lombards; it was agitated by faction, and convulsed by perpetual wars and revolutions during

the middle ages. It has, however, survived these

tempests, and still remains a considerable city. Eustace

Though said to have been destroyed by Totila, Arretium rose from her ashes, withstood all the vicissitudes of the dark ages, which proved so fatal to many of her fellows, and is still represented by a city, which, though shorn of her ancient pre-eminence, takes rank among the chief of Tuscany. Dennis

In the 1970s the tomb of a young Longobard girl of high social standing was discovered inside a Christian cemetery. She was buried without any glass, or ceramic objects or other funerary equipment, but only with jewellery: two

gold bracelets composed of jointed heart-shaped plaques; a

gold ring with blue glass paste in the setting; a pair of

earrings, also in gold, shaped as a basket, decorated with

filigree and pendants adorned with glass paste and amethysts.

Jewellery is the main legacy of the Longobard rule in Italy; see some other jewels which were found at Sutri.

Move to Piazza Grande or to the Cathedral or to a page showing other monuments or go to:

Orvieto - Medieval Monuments

Orvieto - Cathedral and Papal Palaces

Orvieto - Renaissance Monuments

Orvieto - Museums

Cittą della Pieve

An Excursion to Chiusi

Castiglione del Lago

An Excursion to Cortona

An Excursion to Montepulciano

An Excursion to Castiglion Fiorentino