All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in October 2024.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in October 2024.

Perugia - Archaeological Museum

Perugia - Archaeological MuseumYou may wish to see a page on the history of Perugia or on Borgo S. Pietro, the neighbourhood where the museum is located, first.

Upper floor of the cloister of S. Domenico where most of the Etruscan cinerary urns are displayed; (right) funerary "cippi" terminating in a pine-cone

The University of Perugia is rich in Etruscan antiquities, especially urns, inscriptions and bronzes - the produce of the tombs in the neighbourhood.

Among the most ancient relics are some small square cippi of fetid limestone, like those of Chiusi, (..) One of these cippi is circular and displays a death-bed scene. (..) On this monument rests a tall fluted column, terminating in a pine-cone, and bearing a funeral inscription in Etruscan characters. There are other singular pillars - columellae - of travertine, two or three feet high, all bearing sepulchral inscriptions.

George Dennis - The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria - 1848

In 1948 the museum was moved to the architectural complex of the Convent of S. Domenico. Most of the collection comes from XIXth century excavations, including valuable acquisitions such as the Sperandio sarcophagus, the "Cippo di Perugia" stone, and the archaic bronzes of Castel S. Mariano. During this period Perugia established itself as an important centre for archaeological studies regarding the ancient Etruscans. Findings from recent excavations have been added to the collections. Perugia has another small archaeological museum which displays findings from a necropolis south of the town.

(above) Vth century BC "Sperandio" sarcophagus which was found in 1843 in the garden of a Benedictine nunnery (Sperandio means Trust in God); (below) detail of its front relief which depicts a sort of procession

A very singular monument was discovered in a tomb near Perugia, in 1844. It is a sarcophagus of nenfro (a local volcanic stone), with reliefs on three of its sides; those at the ends representing figures reclining at the banquet, one with a lyre and plectrum, attended by slaves; that in the front of the monument displaying a remarkable procession, which demands a detailed description. It is headed by a man with a wand, apparently a herald, preceding three captives or victims chained together by the neck, whose shaggy hair and bears distinguish them as a separate race from the rest - apparently ruder and more barbarous. Two of them carry a small situla or pail in one hand, and a burden on their shoulders, which looks like a wine-skin; the third has his hand fastened by the same rope which encircles his neck. They are followed by two veiled women, engaged in conversation with the man who heads the next group. This is composed of two horses or mules neatly laden, attended by three men, the first with a spear, the next with a helmet and a sword, and the third without weapons, but in an attitude of exultation. A large dog, with a collar round his neck, accompanies these figures. Then march three men with lances, one with a burden on his shoulder, followed by two others similarly armed, driving a pair of oxen and of goats. The subject, from its position on a sarcophagus, has been supposed to be funereal, and to represent a procession of victims to be sacrificed at the tomb. But other than funereal scenes are often found on such monuments; and there are great difficulties attending such an interpretation. It seems to me much more satisfactory to suppose that it is a return from a successful foray. There are the captives bound, and made to carry their own property for the benefit of their victors; their females behind, not bound, but accompanying their lords; their faithful dog following them into captivity; their beasts of burden laden with their goods; their weapons and agricultural implements carried by one of their guards; and their cattle driven on by the rest. That the conquerors have no armour may be explained by supposing them not regular military, but the inhabitants of some border town.

The style of art is very rigid, yet not deficient in expression; and the monument is evidently of early date, undoubtedly prior to the Roman conquest. Dennis

The prevailing opinion about the subject of the relief is still that suggested by Dennis. The sarcophagus contained the body of a warrior, perhaps the leader of a successful military campaign.

In this Museum is an inscription, celebrated as the longest yet known in the Etruscan character, having no less than forty-five lines. It is on a shaft of travertine three feet and a half high and nine inches square; the inscription is on two of its sides, and the letters, which are coloured red, do credit to Etruscan carving. It was discovered near Perugia in 1822. The subject it is in vain to guess at. Sundry attempts have been made at interpretation. (..) A notice attached to it hints that it may possibly refer to agrarian matters. Dennis

Today we know that the text is a legal contract between the Etruscan families of Velthina (from Perugia) and Afuna (from Chiusi), regarding the sharing or use, including water rights, of a property upon which there was a tomb belonging to the Velthina. You may wish to see another long Etruscan inscription dealing with legal matters at Cortona.

Cinerary urns from a tomb excavated in 1797 at Palazzone, south of Perugia, which contained urns of women of the Velimnas family (in the same area in 1840 was discovered another tomb of that family which is shown in a separate page): (left) fight between Ulysses and Scilla; (right) madness of Athamas, a Greek mythological king, in which he slew Learchus, his son, at the instigation of Juno

The Etruscans of Perugia generally burned their dead, for very few sarcophagi are discovered on this site. The cinerary urns are similar to those of Chiusi, but mostly of travertine, though sometimes of nenfro, or a similar dark grey stone; and the urns, it may be, are of the latter, while the figures on the lids are of the former. He who has seen the ash-chests of Volterra and Chiusi, will not find much of novelty here; indeed the urns are interesting rather for their inscriptions, than for their intrinsic beauty or singularity. The subjects are not very varied. Among them are, combats of the Centaurs and Lapithae - the sacrifice of Iphigenia, more common at Perugia than on any other Etruscan site - the hunt of the Calydonian boar - Medusa's head between flowers - Scylla contending with two warriors - Glaucus, or the male deity of the same class, coiling his fishes' tails round the legs of a man armed with a club - a winged female seated on a hippocampus - two men riding on a sea-horse, one playing the Pandean pipes, the other the lyre. Dennis

The image used as background for this page shows a head of Medusa on a cinerary urn.

Cinerary urns of the Rafi which were discovered in 1887 (IInd and Ist century BC): (left) urn of Vel Rafi, the head of the family; (right) Capaneus' assault to the walls of Thebes (see the same subject at Volterra)

This Museum affords proof that the Etruscan modes of burial were adhered to, after the city had become a dependency of Rome; for several urns, truly Etruscan in every other respect, bear inscriptions in Latin letters; though a native character is still conspicuous even in some of these. Dennis

The urn of Vel Rafi stands out from the other ones because he was portrayed as an architect or a master-mason. The usage of making references to the trade of the dead became very common among the Romans of the middle classes (see reliefs at the Necropolis of Porto and inscriptions along Via Appia Antica).

According to the legend, Capaneus had immense strength and body size and was an outstanding warrior. He was also notorious for his arrogance. He stood at the wall of Thebes during the war of the Seven against Thebes and shouted that Zeus himself could not stop him from conquering the town. While he was mounting the ladder, Zeus killed him with a thunderbolt. It is said that he was the first to use ladders in a siege.

Cinerary urns of a less traditional shape with lids with decorative motifs depicting a flower between two "peltae", rather than the statue of the dead at his funerary banquet: (left) Ulysses with the usual felt cap, watches Penelope at her toilet; (right) the punishment of Amycus by Pollux, one of the Argonauts, who was worshipped by the Romans together with his brother Castor

The punishment of Amycus, an arrogant king of the Bebryces, is finely depicted in two bronze exhibits at the Museum of Palestrina, a town south of Rome which had many contacts with the Etruscans: a container (Cista Ficoroni) and a mirror. The subject offered an opportunity for portraying a fight between two strong men, which was emphasized by the red painting of their bodies. Amycus is bearded, a sign that he was regarded as a barbarian.

Bronzes of S. Mariano: reliefs which most likely decorated two VIth century BC ceremonial carriages: (left) a lion and a she-leopard attacking other animals; (right) Jupiter in the act of hitting a giant with a thunder

In bronzes this Museum is much richer than in pottery (but Dennis described a few fine vases from at the necropolis of Palazzone). Here are many laminae of this metal, with reliefs of men, animals, and chimaeras, mostly in a very rigid style of art. A minotaur, or human figure with a bull's head. - A draped female, with a bough on her shoulder and an unguentarium in her hand. - A fragment representing a biga - the horses and charioteer being broken away. - Two small fragments; one with Hercules shaking hands with some divinity who bears a four-pronged sceptre - the other a god, one of the nine great Etruscan deities who wielded the thunder, grasping a man by the hair, who cries for mercy and tries to stay the impending vengeance. -- A winged sphinx, with a tutulus, like a foolscap. Dennis

The usage of decorating ceremonial carriages with bronze plaques passed to the Romans: see a Ist century AD example from Pompeii and a IVth century AD one in Rome.

Bronzes of S. Mariano: (left) Hercules and two Greek infantrymen; (right) element of a tripod perhaps depicting Hebe, the goddess of youth

A fragment, beautifully chiselled, representing the beardless Hercules drawing his bow on two armed warriors. (..) There are also many little deities and other figures in bronze; some of very archaic, even oriental character. (..) All these relics of Etruscan toreutic art, besides others now at Munich, and some reliefs in silver in the British Museum, were found in 1812, on a spot called Castello di S. Mariano, four miles from Perugia, but not in a tomb; which makes it probable that they were buried for concealment in ancient times. They are supposed to be the decorations of sacred or funeral furniture. Dennis

Some oriental features of the depiction of Etruscan men and women have puzzled archaeologists, leading some of them to suggest the Etruscans had an Assyrian or Sumerian origin.

(left) Necklace and earrings from Pila near Perugia (IIIrd century BC); (centre-right) mirror portraying Helen, Laomedon, Castor and Pollux and gold earring both from Ipogeo dei Pesenti (IVth century BC)

The Etruscans possessed advanced metalworking techniques which are very evident in the bronze exhibits of the Museum, less so in its collection of jewels, because most of the tombs were robbed before they were discovered (see some fine Etruscan jewels at Tarquinia, Civitavecchia and Cerveteri).

Cai Cutu Tomb seen from the entrance

In 1983 an intact Etruscan tomb was discovered in the centre of Perugia. It had been excavated deep into the ground rock but its structure was about to collapse. It was therefore decided to reconstruct it inside the Archaeological Museum with the purpose of letting the visitors understand the aspect of an intact tomb, similar to what occurs at the Tomb of the Volumni at the necropolis of Palazzone which was discovered in 1840. Unlike the latter where seven cinerary urns were placed in an orderly manner, this tomb contained fifty urns which were scattered in a rather haphazard way.

They were all related to male members of the same family: Cai Cutu in the oldest urns, then Cutu which was eventually Latinized in Cutius and they are dated from the IIIrd to the Ist century BC.

The reliefs which decorated the urns are similar to those found elsewhere and had similar subjects so it was felt more important to show the overall tomb than the single urn.

Stuccoed cinerary urn of Arnth Cai Cutu

The magnificent urn of Arnth Cai Catu is separately displayed and it is replaced by a copy inside the tomb. It is probably a work by the same artisans who made the urn of Arnth Velimnas Aules; the latter wears a sort of long torque/necklace, which was a sign of social distinction, whereas Arnth Cai Cutu does not, so it is thought he had a servile origin. His bare torso was very finely shaped and calls to mind classical models.

Cinerary urns of the Cacni which were recovered in 2013 by Italian authorities: (left) fight between Eteocles and Polynices, a popular subject, especially at Chiusi; (right) cinerary urn of a couple with a rose decoration

In 2003 tombaroli (grave robbers) discovered an Etruscan tomb in the northern part of Perugia; urns, jewels and other findings were sold in the antiquarian market, but in 2013 Italian Carabinieri managed to recover 22 cinerary urns and to identify the site of the tomb between Arco Etrusco and Porta Trasimena, along the ancient road leading to Cortona and Chiusi.

The urns are dated IIIrd and IInd century BC, a period of prosperity for Perugia. The depiction of a couple is not unusual at Perugia and some other fine examples have been found at the necropolis of Ponticello di Campo. Sarcofago degli Sposi, the best known Etruscan sarcophagus, was made for a couple.

The museum houses also a fine Etruscan cinerary urn from Castiglione del Lago.

Roman mosaics: (left) from Via Balbo (Ist century BC - see similar mosaics at Villa dei Volusii near Rome and at Verona); (right) from Piazza Morlacchi (early VIth century AD - see similar patterns at Villa del Casale in Sicily and at Aquileia)

The museum retains little evidence of Roman Perugia: inscriptions, some mosaics, a marble cinerary urn which was used as baptismal font in the cathedral and a sarcophagus. Its official name is Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell'Umbria (MANU), but in the region there are other important archaeological museums at Orvieto, Spoleto, Terni and Narni.

Roman sarcophagus depicting the death of Meleager from Farfa (IInd century AD)

After 1861 Perugia became the capital of a province which included the whole of Umbria and Sabina, a region to the east of the River Tiber, not far from Rome, which today is part of Latium. This explains why two Roman sarcophagi which were utilized by the abbots of Farfa, a very important medieval monastery were moved to the museum of Perugia.

Meleager is usually portrayed in the act of killing the Calydonian boar (e.g. in a sarcophagus at Vicovaro, not far from Farfa), but soon after that event he was involved in a war against the Curetes, a legendary people who took part in a quarrel over the spoils of the boar. They were supported by Apollo, who killed Meleager. According to another version the quarrel was between Meleager and his uncles.

Roman sarcophagi: (above) Dionysus on his panther and his followers (III century AD); (below) a "strigilato" sarcophagus from Farfa which was used for Abbot Berardo d'Orte (d. 1089)

Thiasos, a procession of followers of Dionysus was a very popular subject in marble sarcophagi (see a list of them in Rome), especially in the Late Empire. A very similar sarcophagus was found at Bolsena.

A decoration based on strigiles, columns and the typical Roman inscription frame is very common, see two sarcophagi at Poli.

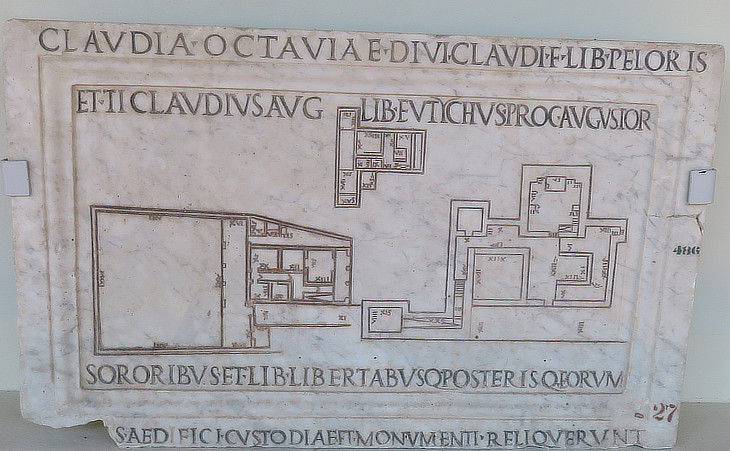

Marble plan of buildings of Rome from Collezione Oddi Baglioni

Some of the wealthiest families of Perugia had collections of Roman reliefs, inscriptions and small objects which they had bought to embellish their palaces. These collections were acquired by the Museum of Perugia. One of the most interesting items is a marble plan depicting with extreme exactness some funerary buildings belonging to the liberti (freedmen) of Emperor Nero (who is referred to as the son of deified Claudius) and his first wife Claudia Octavia. The plan indicates the length of the walls, even those of some tiny rooms. The location of these buildings in Rome has not been identified.

See a tomb in Rome with inscriptions exactly indicating the size of the property and the Museum of Forma Urbis Romae, a IInd century AD marble map of Rome.

Move to Walls and Gates, The Two Piazzas, The Papal Street (Borgo S. Pietro), S. Pietro de' Cassinesi, The Tomb of the Volumni or wander about to see other churches, palaces and fountains.