All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in September 2021.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in September 2021.

- Roman Funerary Rites

- Roman Funerary Rites| Est honor et tumulis. Animas placate paternas parvaque in extinct as munera ferte pyras. parva petunt manes, pietas pro divite grata est munere: non avidos Styx habet ima deos. tegula porrectis satis est velata coronis et sparsae fruges parcaque mica salis inque mero mollita Geres violaeque solutae: Ovid - Fasti - Book II - vv. 533-539 (more on Ovid) |

Honour is paid, also, to the tombs. Appease the souls of your fathers and bring small gifts to the extinguished pyres. The ghosts ask but little: they value piety more than a costly gift: no greedy gods are they who in the world below do haunt the banks of Styx. A tile wreathed with votive garlands, a sprinkling of corn, a few grains of salt, bread soaked in wine, and some loose violets, these are offerings enough: Translation by Sir James George Frazer |

Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia in Rome: Sarcophagus of the Spouses (terracotta - VIth century BC)

Then put off every man his armour, they took the horses from their chariots, and seated themselves in great multitude (..) (and they) feasted with an abundant funeral banquet. Many a goodly ox, with many a sheep and bleating goat did they butcher and cut up; many a tusked boar moreover, fat and well-fed, did they singe and set to roast in the flames of Vulcan; and rivulets of blood flowed all round the place where the body (of Patroclus) was lying. Omer - The Iliad - Book XXIII - Translation by Samuel Butler

In most ancient civilizations a banquet was a key element of funerary rites and it was depicted in many gravestones, vases and paintings (e.g. at Paestum). The Sarcophagus of the Spouses was found at the necropolis of Cerveteri and it portrays a couple attending a funerary banquet. It did not contain the bodies of the dead, but their cinerary urns. It shows that in Etruscan society women had a more important role than in the Greek one which did not allow them to attend such banquets. There is no sign of grief in the slightly smiling faces of the couple; they seem to welcome their guests to a festive party. They held something in their hands, perhaps a fruit, or an egg or a flask with perfume.

Although similar sarcophagi were used by the Etruscans for many centuries (see pages on Tuscania and Tarquinia) they were not popular among the Romans, whose family tombs were expected to house a very large number of cinerary urns in a small space (e.g. Sepolcro degli Scipioni).

Museo Archeologico Nazionale d'Abruzzo: funerary bed with bone decorations from the Necropoli of Fossa near L'Aquila (Abruzzo) (IInd-Ist century BC) which was discovered in 1992

Inhumation continued to be practiced in some inland locations of Italy whose inhabitants had retained their practice of individual tombs. The dead was laid upon a finely decorated funerary bed. It is likely that the bone reliefs portrayed Hercules (because of the lion, his first labour) and Dionysus (in his early iconography). See a similar funerary bed in a relief of a sarcophagus from Beirut, another bone decorated bed from Abruzzo and some Greek bronze bed decorations in the museums of Marseille and Rabat.

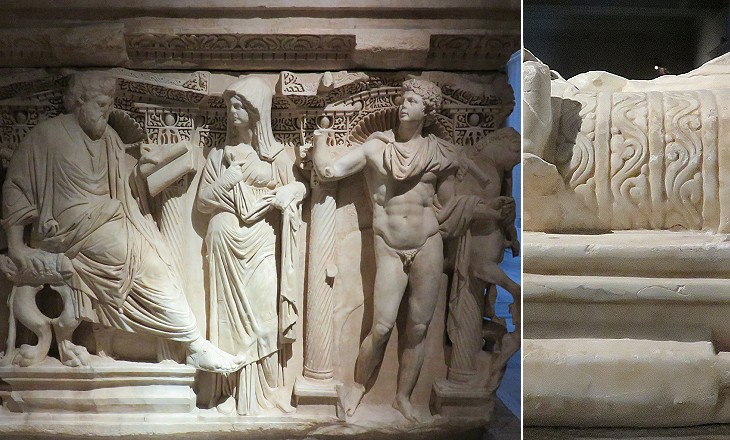

Archaeological Museum of Antalya: large-scale sarcophagus from Perge

During the IInd century AD the practice of inhumation gained ground versus that of cremation owing to a general move of society towards beliefs which implied some forms of resurrection.

Stone sarcophagi had been widely used in many regions of Asia Minor along the Aegean Sea from Assos in the north to Xanthos in the south. In the IInd century AD this practice spread to many parts of the Roman Empire. Building upon the availability of fine-grained white marble at Docimeium, near today's Afyonkarahisar, many workshops in Asia Minor began to make elaborately decorated sarcophagi for wealthy customers.

The workshops had different "production lines", one of which, similar to the Sarcophagus of the Spouses, portrayed the dead attending a banquet on the lid.

Archaeological Museum of Antalya: large-scale sarcophagus from Perge - rear side

The sarcophagus found at Perge shows the high level of skill (and talent) available in the workshop where it was made. The execution of the complex Dionysiac scene is excellent both in the front, where a high relief technique was used (with figures projecting or entirely detached from the background), and in the back, where low relief was used. The use of different relief levels is due to the fact that in Asia Minor sarcophagi were placed at the centre of the room, so they had to be decorated on all sides, whereas in Rome they were placed against a wall and a projecting decoration of the rear side would have been an obstacle to their positioning. This sarcophagus was not made to order and its lid left the workshop in half-finished condition. The portraits of the dead were completed at a later time, after they had reached their final destination, by local skilled workmen.

Archaeological Museum of Antalya: large-scale sarcophagus from Perge - embroidered cushion (see a similar cushion in a sarcophagus at Musei Capitolini)

Stiacciato (It. schiacciato, pressed) is the name given to a very low relief used in the XVth century by Donatello and other Renaissance sculptors including Giovanni Dalmata. In this sarcophagus stiacciato was used for the embroidered cushion of the couch to depict hunting scenes. The complex decoration of the sarcophagus did not include references to death.

Archaeological Museum of Istanbul: Sidamara sarcophagus from Konya

The Management of the Museum classifies this sarcophagus as a Sidamara one, after the location near Konya where sarcophagi with figures framed by niches were found. In the front side of the sarcophagus however the orderly frame provided by the niches is hardly noticeable and the decoration is an explosion of life which invades the lid. This approach suited very well the depiction of the Labours of Hercules.

Archaeological Museum of Istanbul: sarcophagus from Konya: (left) detail of the rear side showing a poet reading his lines to a Muse (or Helen of Troy) and one of the Dioscuri; (right) embroidered cushion

The decoration of the rear side is more composed with the niches being given more prominence. They were made with yet another technique: it was based on the use of a drill to obtain a series of holes which depicted their architectural elements. The use of drills became very common in Byzantine art, especially for making very elaborate capitals (e.g. at Sts. Sergius and Bacchus at Constantinople).

Archaeological Museum of Izmir (Smyrna): lid of a sarcophagus from Ephesus

The box of this sarcophagus is lost, but based on the lid, we may assume it had a very carefully designed decoration. Lavoro di bottega (workshop work) is a term often used by Italian art historians to indicate a statue or a painting by an unidentified artist which do not have peculiar features. When instead the work of art departs from routine its unidentified author is named after it e.g. Maestro del Duomo di Orvieto indicates the author of some of the reliefs which decorate the Cathedral of Orvieto.

Archaeological Museum of Izmir: lid of a sarcophagus from Ephesus - details

A similar approach ought to be followed for these sarcophagi and other works of art of the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The focus on the art of Classical Greece (Vth century BC) which began in the XVIIIth century has dubbed as decadent the works of art made after that period. This view has been helped by the fact that sculptors did not hold a high position in the Hellenistic/Roman societies and we know the names of a handful of them. Art historians ought to deepen their studies into these works of art and not just label them by the period they were made and the location where they were found. The scenes depicted on this lid deserve it.

Museum of Ostia Antica: sarcophagus found near Porto

This sarcophagus shows such a similarity with that of Perge that it is likely it was made in the same workshop and then sent to a dealer at Ostia who sold it to the final customer. It has small holes in the box and in the lid (holes missing in the sarcophagi of Asia Minor). The holes were made by unskilled hands and they were used for profusiones, pouring in of wine or milk or pieces of cakes in honour of the dead. This practice of piety was eventually reprimanded by Saint Ambrose in the late IVth century: When my mother had once, as she was wont in Africa, brought to the Churches built in memory of the Saints, certain cakes, and bread and wine, she was forbidden by the door-keeper: so soon as she knew that the Bishop (St. Ambrose) had forbidden this, she so piously and obediently embraced his wishes. St. Augustine - The Confessions - Book VI - 2 - Translation by Edward Bouverie Pusey.

Museum of Ostia Antica: sarcophagus found near Porto - details: (left) side decoration (the image used as background for this page shows the small "dog", or rather a Roman "Teddy" bear); (right) details of the embroidered cushion

In the side decoration is interesting to note: a) the sculptor designed a motif based on studs for the two wooden supports between which the cushion was placed;

b) the children are in a joyful mood, but one of them, in a rather nonchalant manner, holds down a torch, a symbol of death (but perhaps a reference to Ovid's words: While these funerary rites are enacted, girls, don't marry.

Let the marriage torches wait for purer days).

Ovid made reference to Feralia, a public holiday on February 21st which celebrated the souls of the dead. In addition to this general commemoration, funerary rites including profusiones

were performed on the birthday of the dead and not on the anniversary of their death.

Most tombs of the rich had a small hall where these ceremonies were performed. It was placed above the underground room where sarcophagi and cinerary urns were kept (as it can be seen in many of the brickwork tombs along Via Appia Antica).

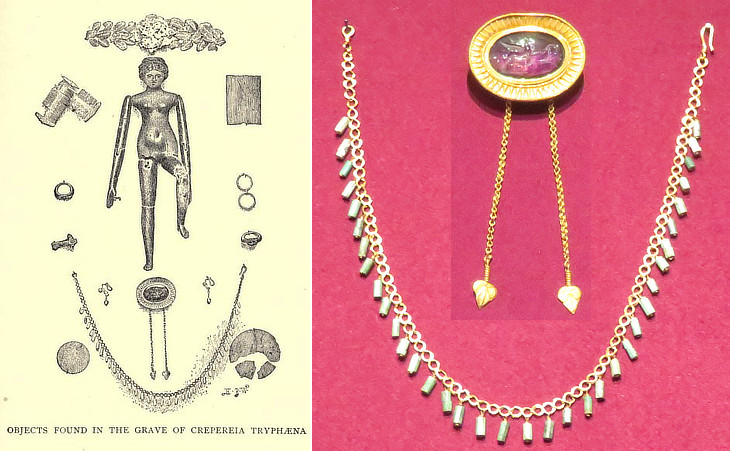

Centrale Montemartini: (left) illustration from "Rodolfo Lanciani - Pagan and Christian Rome - 1892" showing the objects which were found in the grave of Crepereia Tryphaena in 1889; (right) two of the jewels

The dead undertook their journey to the underworld with some of their most cherished clothes, jewels, objects. Sarcophagi were very rarely found intact, but when this occurred even the most expert archaeologists could not hide their excitement when they broke the seals and put the lid aside.

The skull was inclined slightly towards the left shoulder and towards an exquisite little doll, carved of oak, which was lying on the scapula, or shoulder-blade. On each side of the head were gold earrings with pearl drops. Mingled with the vertebrae of the neck and back were a gold necklace, woven as a chain, with thirty-seven pendants of green jasper, and a brooch with an amethyst intaglio of Greek workmanship, representing the fight of a griffin and a deer. Where the left hand had been lying, we found four rings of solid gold. One is an engagement-ring, with an engraving in red jasper representing two hands clasped together. The second has the name PHILETVS engraved on the stone; the third and fourth are plain gold bands. (..) Scrofula seems to have been the cause of her death. In spite of this deformity, however, there is no doubt that she was betrothed to the young man Philetus, whose name is engraved on the stone of the second ring, and that the two happy lovers had exchanged the oath of fidelity and mutual devotion for life, which is expressed by the symbol of the clasped hands.

Rodolfo Lanciani - Pagan and Christian Rome - 1892

Read more of Lanciani's account and see the doll and other objects in a page on the location where the sarcophagus was found (Palazzo di Giustizia).

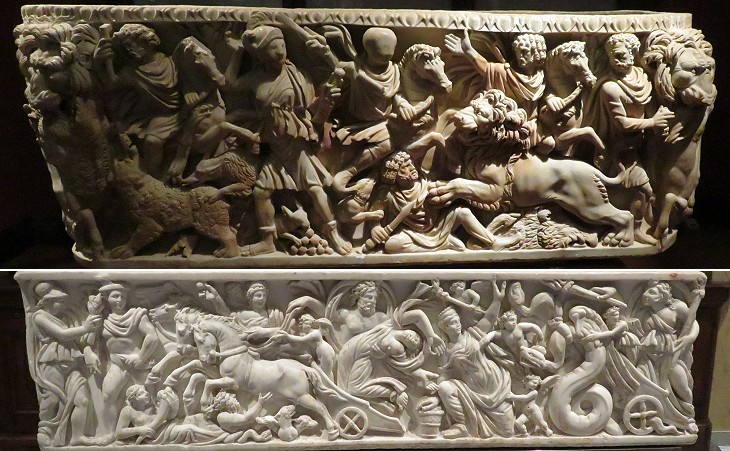

Musei Capitolini in Rome: sarcophagus found near Vicovaro depicting Meleager killing the Calydonian Boar

How sharper than a serpent's tooth it is / To have a thankless child!

William Shakespeare - King Lear - Act I

Usually the wealthy Romans who could afford an expensive marble sarcophagus left enough money in their will for the performance of periodical funerary rites. Something must have gone wrong at Vicovaro. Not only this sarcophagus does not have the holes for profusiones, but the heirs did not care to hire a local sculptor to actually portray the dead out of the roughly designed heads made at the workshop.

Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna: (above) scene of lion hunting; (below) Rape of Proserpina

The first sarcophagus is another instance of unsold sarcophagus; it was very finely carved in all details except the faces of the horseman and of the nearby goddess. Both sarcophagi did not have spaces for inscriptions which most likely were placed on the lid. They were part of a collection of antiques which Francis V, Duke of Modena moved to his palace in Vienna when he was about to be ousted from his duchy in 1859. The collection was gathered during the course of many centuries and the exact location where the sarcophagi were found is no longer known. In other instances the origin of sarcophagi is not stated because they were acquired in violation of the law.

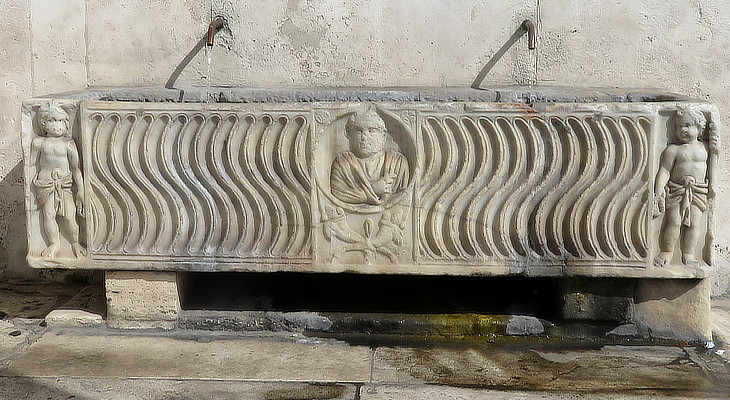

Piazza del Popolo: fountain making use of a IIIrd century AD sarcophagus next to a building designed by Giuseppe Valadier

Sarcophagi with statues of the dead on the lid and elaborate reliefs on the box were very expensive; patterns were developed to reduce costs; the dead was portrayed in a small clipeus (round shield) at the centre of the box (see a fine funerary relief with multiple clipei); the reliefs were replaced by a decorative motif based on strigilis, a double curved tool athletes used to scrape oil or sweat from the skin. The end of the box or its sides had reliefs having a protective purpose: genii holding symbols of life and death, heads of Medusa, lions, etc. Many of these "ordinary" sarcophagi were eventually utilized as water containers in the courtyards of Roman palaces.

Musei Vaticani: Christian sarcophagi: (above) Miracles of Jesus and his entrance into Jerusalem; (below) Crossing of the Red Sea

The use of sarcophagi persisted after the majority of the population of the Roman Empire embraced the Christian faith, but the practice of placing on the lid a statue of the dead attending a funerary banquet was discontinued. Members of the imperial family were buried in porphyry sarcophagi, e.g. St. Helena, Emperor Constantine's mother. Events from the Old and the New Testament replaced mithological tales in the reliefs of the boxes; in general sculptors refrained from depicting nudity, but not always. Episodes such as the Crossing of the Red Sea gave the opportunity to continue to depict chariots and war scenes, a subject which had been very popular in the past.

Funerary monument to Silvestro Aldobrandini by Nicolas Cordier at S. Maria sopra Minerva

The typical funerary monument of a medieval pope or sovereign was a gisant in which the dead was portrayed lying in eternal repose. During the Renaissance however some ancient sarcophagi were found and they had an influence on Nicolas Cordier and Pope Clement VIII, his patron: the father of the Pope was portrayed in a pose similar to that in the ancient sarcophagi. Another attempt of using this pattern was made by Ercole Ferrata at Cappella Spada in S. Girolamo della Carità, but eventually other types of funerary monuments were developed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini which were more in line with the doctrine of the Roman Church (see a page on Baroque Sculpture).

Move to a list of sarcophagi which were found in Rome and its environs or in countries which were part of the Roman Empire and which are shown in this website.