All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in January 2021.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in January 2021.

- Museums near Topkapi Sarayi

- Museums near Topkapi SarayiYou may wish to see an introductory page to this section first.

The first Ottoman museum was founded in 1869 and its exhibits were displayed in Hagia Irene. Because the space in the ancient church soon became insufficient, the collections were moved to Cinili Kosk (Tiled Pavilion) in the garden to the north of Topkapi Sarayi. Eventually the government built two palaces near Cinili Kosk to provide Constantinople with a museum which could withstand comparison with those of Paris, London and Berlin, where many works of art from territories of the Ottoman Empire were on display.

Archaeological Museum: "Sidamara" sarcophagi found in Turkey, a type of sarcophagi characterized by columns and niches in order to resemble a building (named after a small town near Konya where one of them was first found)

Today the main building houses the Archaeological Museum, a smaller building houses the Ancient Orient Museum and the Cinili Kosk houses a collection of Ottoman tiles. Similar to what occurs at many other large museums there is always a section which is in the process of being enlarged/redesigned or maybe is closed because of manpower shortages. In April 2015 some parts of the Archaeological Museum were closed, including that housing the "Alexander Sarcophagus", one of the masterpieces of its collections.

Archaeological Museum: (left) statue of a woman from Afrodisias; (right) Head of Medusa from Kutahya

After the establishment of the Republic of Turkey and the move of the capital to Ankara in 1923, the new government promoted the opening of archaeological museums at a local level. The works of art unearthed after 1923 were no longer sent to the Archaeological Museum of Constantinople/Istanbul. Many exhibits of the museum are shown in pages covering the locations where they were found (e.g. the reconstruction of a Palmyrene necropolis can be seen in a page covering that ancient city). The exhibits related to Byzantium/Constantinople are shown in a separate.

Archaeological Museum: (left) statue of a hunter from Cyrene (IInd century AD); (right) Phoenician sarcophagus from Gaza (Vth century BC)

In 1861 the British Museum was presented with a large number of Roman sculptures which had been found at Cyrene, in today's eastern Libya. They had been excavated by Captain Robert Murdoch Smith and Commander Edwin A. Porcher. According to an account of the archaeological expedition they wrote in 1864, they moved the pieces away secretly, fearing the marble fragments would be further destroyed by the locals because the sculptures were non-Islamic. Eventually a controversy with the Ottoman government arose and in 1870 the statue shown above was sent to Constantinople to settle the issue.

In 1881 Osman Hamdi Bey was appointed director of the Archaeological Museum; in the following years he conducted a series of excavation campaigns. At Sidon in Lebanon he found a series of very interesting sarcophagi.

The Museum houses a number of early Phoenician sarcophagi. They were decorated with impressive portraits of the dead as you can see in those at the National Museum of Beirut.

Ancient Orient Museum: statues from Mesopotamia: the third statue from the left portrays Shalmanaser III, King of Assyria in 859-824 BC

Mesopotamia, (the land) between rivers, was regarded as the cradle of civilization in the western world. In the XIXth century it attracted many foreign travellers and archaeologists. At that time it was within the borders of the Ottoman Empire with just a small south-eastern section belonging to the Persian Empire (today it is split among Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran). A large number of ancient statues, reliefs and inscriptions ended up in European and American museums and private collections. A limited number of them were acquired by the Ottoman government, directly or as a form of fee paid by foreign archaeological expeditions. The exhibits of the Ancient Orient Museum are all dated before the VIth century BC and they include Hittite statues and reliefs found in south-eastern Turkey.

Museum of Ancient Orient - bronze strip from the gates of Balawat (IXth century BC) near Nimrud in Assyria (enhanced contrast)

Balawat was a small ancient Assyrian town where in 1878 a local archaeologist found three gates closed by cedar doors. The wood was rotten and vanished, but the doors were decorated with bronze strips depicting military campaigns of King Shalmaneser III, sacrifices and other subjects similar to those which decorate the Persepolis palace of Emperor Darius. Most of the bronze strips are at the British Museum, but a few of them are in Istanbul.

Museum of Ancient Orient - relief portraying an auroch (extinct ox with massive horns) from the Procession Street of Babylon (VIth century BC)

Robert Johann Koldewey was a German archaeologist who unearthed the Ishtar Gate and the Procession Street of Babylon between 1904 and 1912. They were decorated with more than a hundred reliefs made with blue, black and yellow bricks and depicting aurochs, dragons and lions. Many of them are at the Pergamon Museum of Berlin, but they can be found in more than ten other museums in Europe and America.

Cinili Kosk (Tiled Pavilion - see its side towards the gardens)

This pavilion was inaugurated in 1472, so it is one of the oldest buildings of Topkapi Sarayi. The area in front of it, before being occupied by the Archaeological Museum, was a field for cirit tournaments, a team sport played on horseback which recalls polo. This may explain why the pavilion has such a long terrace; it was most likely used by the Sultan and his court to watch the matches.

Cinili Kosk: (left) entrance; (right) detail of its long inscription

The design of the building with its deep iwan (recess), its tile decoration based on different tones of blue and the Kufic inscriptions on the iwan ceiling shows the influence of Persia. These features can be seen in the XIVth century portal of the Friday Mosque at Yazd.

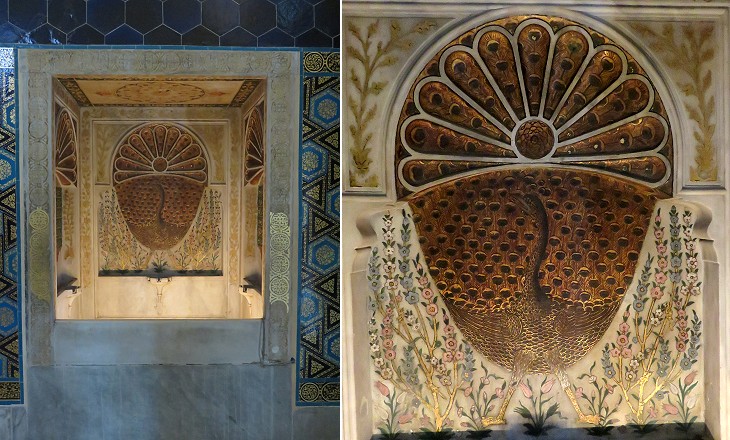

Cinili Kosk: XVIIIth century selsebil (fountain) from Gulhane park

Quite rightly Cinili Kosk has become a small tile museum which includes some exhibits from other towns (e.g. a mihrab from Karaman). In addition it houses a fine selection of typical Ottoman plates. You may wish to see a similar museum at Kutahya.

Cinili Kosk - Iznik plates (late XVIth century)

The image used as background for this page shows a detail of a plate at Cinili Kosk.

Louvre Museum in Paris: Iznik tiles

Plan of this section:

Introduction

Roman Monuments

Hagia Sophia

Hagia Irene and Little Hagia Sophia

Roman/Byzantine exhibits at the Archaeological Museum

Great Palace Mosaic Museum

St. Saviour in Chora

Byzantine Heritage - Other Churches (before 1204)

Byzantine Heritage (between 1204 and 1453)

First Ottoman Buildings

The Golden Century: I - from Sultan Selim to Sinan's Early Works

The Golden Century: II - The Age of Suleyman

The Golden Century: III - Suleymaniye Kulliye

The Golden Century: IV - Sinan's Last Works

The Heirs of Sinan

Towards the Tulip Era

Baroque Istanbul

The End of the Ottoman Empire

Topkapi Sarayi

The Princes' Islands

Map of Istanbul and key dates of its history

Warwick Goble's 1906 Constantinople