All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in July 2021.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in July 2021.

- Roman Beirut

- Roman BeirutYou may wish to see an introductory page to this section first.

Ancient granite columns which have been re-erected on the assumed site of the crossing between the two main streets of Roman Beirut near the Forum of the town

The city of Bayrout is the ancient Berytus. (..) It is situated over the sea on a gentle rising ground, on the north

side of a broad promontory. (..) Augustus when he made

it a colony, called it after the name of his daughter, with the epithet

of happy, naming it Colonia Felix Julia. (..) This city was antiently a place

of study, more particularly of the civil law, and especially about the

time that Christianity began to be publickly established. (..) There are several granite pillars

about the town, and particularly six or seven of grey granite in one part,

some standing, and some lying on the ground.

Richard Pococke - A Description of the East and Some Other Countries - 1745

In the afternoon I walked about the

town with Signer Meskel; it contains but few remains

of the ancient Berytus: it is small, and surrounded by

a wall with five gates, built by the late Pasha of Acre,

Djeazar, who is still talked of as a great man, though

he died ten years ago; a great length of posthumous

fame for a Turkish Pasha. (..) There are

scattered about it numbers of large granite columns,

without pedestals or capitals.

William Turner - Journal of a Tour in the Levant - 1820

(above) National Museum of Beirut: inscription celebrating the restoration of a building by Agrippa II and his sister Berenice; (below-left) American University of Beirut Museum: inscription in honour of Emperor Antoninus Pius; (below-right) NMB: Roman eagle holding a snake tail. All found in Beirut

In ca 125 BC merchants from Berytus built on Delos in the Aegean Sea a Temple to Poseidon, actually a hall for their meetings. This indicates that the town had strong trading links with Greek cities which at that time were under the control or patronage of Rome. Berytus was not among the most important towns of Phoenicia when the Romans took control of the region in 63 BC, but Augustus chose it for establishing there a colony because he knew that its mercantile class was not hostile to Rome. The inscription mentioning Agrippa II suggests that he paid for the restoration of a building in order to ingratiate himself with the Roman citizens of Berytus.

Foundations of Petit Serail (Small Palace) a late XIXth century Ottoman building at Place des Martyrs: (inset) ancient Roman materials which were found during the excavations in the mid 1990s

The pre-Roman town stood on a tell, a low hill between today's Place des Martyrs and the sea to its north. In 1994, in the frame of a large project for the reconstruction/redevelopment of the city centre after the Civil War (1975-1990), the whole neighbourhood over the site of the ancient town was bulldozed and dumped into the sea. In the process the foundations of Petit Serail (which was demolished in 1950 in the frame of another development project) were uncovered and many ancient materials which lay under them were brought to light. If proper archaeological excavations had been made greater knowledge of the early history of Berytus would have been acquired.

(above and below-left) National Museum of Beirut: sarcophagi; (below-right) American University of Beirut Museum: another sarcophagus

To-day I saw more of the town than

I had yet done; like all Turkish towns, the streets

are narrow, badly paved, and dirty. (..) At one of the

gates (..) is a water trough

of bad workmanship, and quite broken; evidently Roman. Turner

The water trough mentioned by Turner might have been the box of a stone sarcophagus which stands outside the National Museum. Pococke and Turner were both keen in describing all the ancient monuments they saw, but they had little to write about those of Berytus, which were destroyed by a major earthquake followed by tsunami and fire in July 551.

(above) Central section of the Roman baths behind the Parliament Building; (right) frieze found in the baths

The presence of Roman public baths behind the Parliament Building in the 1930s city centre was discovered in 1968. In the 1990s a small archaeological area was designed to protect the baths which were in part excavated into the rock. They had the usual hot, tepid and cold halls and heating system of such Roman facilities.

Section of the Roman baths with a "natatio", the low pool of the "frigidarium" (cold room) which was faced with marble

Excavations and studies by French archaeologist Jean Lauffray (1909-2000) detected the main elements of the urban layout of Roman Berytus. The usual rectangular design of a Roman town had to be adapted to the unevenness of the rocky ground as shown by the baths. Over time four bath establishments have been identified in Beirut. You may wish to learn about what went on at an ordinary bath establishment of Rome in the words of Seneca.

Archaeological site of the Roman Forum between Place de l'Etoile and Place des Martyrs

In the 1940s parts of the Roman Forum were uncovered in the city centre and subsequent excavations unearthed also a colonnaded cardo (south-north street). The earthquake which struck Berytus in 551 added its devastating effects to those of a plague which is thought to have killed a quarter of the population in the Eastern Mediterranean countries in the 540s and even more at Constantinople. Berytus was not abandoned, but the inhabitants who survived these disasters did not have the resources to rebuild its monuments.

Columns and lintel opposite the National Museum of Beirut

The columns and the fine frieze above them were part of a basilica in the Roman Forum. They have been reconstructed opposite the National Museum of Beirut. During the Civil War the museum was on the demarcation line between Christian and Muslim militias. The building and many of its exhibits suffered extensive damage, yet the bulk of the collections was saved thanks to the action of the museum directors. The museum was reopened in 1999. It is very well arranged and it does not have the spectacular light effects which characterize some contemporary redesigns of historical museums and do not permit a proper examination of the exhibits (e.g. at Antalya and Burdur).

Al Omari Grand Mosque, former Church of St. John Baptist: view of the apse and of its windows in which some ancient stones were used

This town was taken from the Saracens by Baldwin, king of Jerusalem, after a vigorous siege; in one thousand one hundred and eleven, and was retaken by Salladine in one thousand one hundred and eighty seven; it was afterwards often taken and retaken during the holy war. In the middle of the city there is a large well built mosque, supported by Gothic pillars, which was formerly a church dedicated to St. John. Pococke

Al Omari Grand Mosque: (left) Mameluke entrance incorporating some ancient materials; (right) modern courtyard with Roman columns (the building was partially damaged during the Civil War)

The mosque/church stands very near the Roman Forum and it was built on the site of Roman baths making use of columns, capitals and marbles taken from them. The building is dated 1150, with some XIVth century Mameluke additions, but there is evidence that it replaced a previous mosque which in turn was obtained from the transformation of a Byzantine church. The mosque is dedicated to Omar, the second Caliph and a companion of Prophet Muhammad. He is highly regarded by the Muslim Sunnis of West Beirut, less so by the Muslim Shias who mainly live in the Bekaa Valley and in southern Lebanon.

(left) Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St. George: copy of a mosaic of an early Christian church which was found beneath the current one in 1995; (right) column with Latin inscription outside the church

At half-past four I strolled out and looked at the

Greek church, which is the largest I have yet seen in the country, being about 120 feet long, and 70 high.

It is very handsomely adorned with gildings and a

marble mosaic pavement. Turner

The cathedral was largely modified in 1910. It was shelled during the Civil War. Excavations made during its reconstruction unearthed a number of artifacts of previous buildings.

Ruin of a castle of the Crusaders which stood near the old harbour

The old port is a little bay, and was well secured by strong piers, which were destroyed by Fackerdine (Emir of Lebanon in 1591-1635). Pococke

At day-light we saw the extreme coast of the Mediterranean, and at half past nine, to my great delight, anchored in the bay of Barout. At a quarter before ten a small boat came off to us from the shore, into which I jumped, leaving my servant on board with the baggage, till the wind, which still blew very high, should calm. (..) As the town stands in a large bay, at the northern extremity of which ships are forced to anchor in a high wind, we had two miles to accomplish in our little boat, into which part of every wave entered. (..) The town formerly possessed a small port, but there is now only a small mole projecting into the sea. (..) At a quarter past eleven our boat landed us at the

town, which is defended by a few ruined towers of

late date. Turner

In 1860, in order to provide Beirut with proper harbour facilities, an old castle was demolished. In 1995 during the redevelopment of the area, similar to what occurred at Petit Serail, its foundations were brought to light and it was discovered that the walls of the castle were strengthened by using Roman granite columns, a practice which can be observed at many other locations e. g. at Sidon, at Kos and at Caesarea.

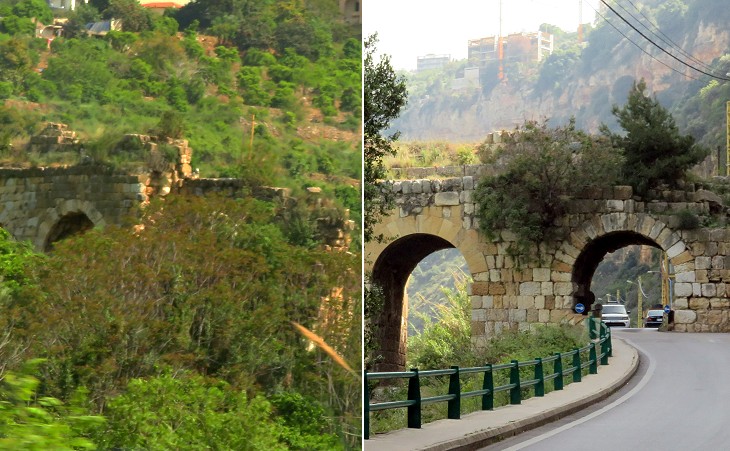

Qanater Zbeideh, a Roman aqueduct over Nahr Bayrut, a small stream in the suburbs of Beirut

The Roman town was supplied with water by an aqueduct which was utilized until the 1870s. Some of its arches can still be seen across a deep valley south of Beirut. Zbeideh is a corruption of Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra who briefly ruled some eastern provinces of the Empire. The aqueduct is dated 273 AD and it was most likely built by Emperor Aurelian who defeated and captured Zenobia in 272.

National Museum of Beirut: statues from Beirut: (left to right) a male torso, perhaps from a statue of Jupiter or of an emperor (see similar statues at Catania and Caesarea); Mercury; a Roman commander or emperor

The National Museum houses many works of art which testify to the wealth of Berytus. They are evidence of a very Hellenized society. Some of the exhibits were most likely imported from other parts of the Roman Empire, especially today's Turkey

National Museum of Beirut: long side of a sarcophagus from Beirut depicting a funerary banquet

Very often sarcophagi were decorated with reliefs depicting gods and mythological heroes, but this one provides us with interesting details of the life of a Roman matron; she is portrayed on an elegant couch with her servant and a pet dog; unfortunately she is dead, but the sculptor purposefully ignored perspective rules to shows two eggs she is about to eat and the eggs are a symbol of immortality.

National Museum of Beirut: gravestone of Caius Julius Verus, "gladiarius" (sword maker) from Beirut (notice the sword on the floor)

While in general funerary inscriptions of the Roman period which were found in Lebanon were written in Greek, the inscription of this gravestone is in Latin and the name of the dead could not be more Roman. It shows that for a period of time Berytus retained the imprint of the Roman colony founded by Augustus.

National Museum of Beirut: mosaic from Beirut depicting a "Nilotic scene"

This type of coloured mosaics was initially developed at Alexandria, but it soon spread to other parts of the Empire, including Rome. It was a mosaic which required a lot of skilled craftsmanship and was difficult to repair, so only the very wealthy could afford it. It depicts many animals in a swamp including a ferocious crocodile to indicate that the scene is set in Egypt. A complex Nilotic mosaic which shows also the Nilometer, the instrument for measuring the river level, can be seen at Sepphoris, a very Hellenized town in Galilee.

National Museum of Beirut: mosaic from a church at Jnah in the environs of Beirut depicting birds and palm trees (Vth/VIth century - it was found in the 1960s)

While the Vth century saw the decline and collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern one continued to enjoy a degree of stability and prosperity at least until the plague of the 540s. Private residences and churches were embellished with large coloured mosaics even in regions which were relatively poor as those to the east of the Dead Sea as shown by the mosaics of Madaba. One of the finest mosaics of a Lebanese church was found at Qabr Hiram near Tyre in 1861 (now at the Louvre Museum).

National Museum of Beirut: mosaic from a church at Jnah in the environs of Beirut depicting a shepherd and a variety of animals (Vth/VIth century - it was damaged during the Civil War)

Christian mosaic makers renovated the pagan catalogue of subjects by introducing references to episodes of the Old and New Testaments in addition to Christian symbols (e.g. peacocks, pomegranates, shells, etc). In this mosaic a traditional and very popular subject, i.e. Orpheus taming the animals (see a mosaic at Philippopolis) was adapted to the new religion by replacing the legendary Greek musician and poet with a shepherd symbolizing Jesus Christ (see also a famous mosaic at Ravenna).

Airport of Beirut: Roman period statue of a lion found at Beirut

The image used as background for this page is based on the modern coat of arms of the City of Beirut: it shows a ship carrying an open book, a reference to the law school of Berytus (see the ship on a bench at Corniche Manara).

Move to see some postcards from today's Beirut.

Plan of this section:

Introductory page

Anjar

Baalbek

Beirut

Beiteddine

Deir el-Qalaa

Deir al-Qamar

Byblos (Jbeil) and Harissa

Qadisha Valley

Qalaat Faqra

Sidon

Tripoli

Tyre