All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in January 2020. The photos were taken in 2005 and 2019.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in January 2020. The photos were taken in 2005 and 2019.

- A political manifesto: Karlskirche

- A political manifesto: KarlskircheYou may wish to read an introduction to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nations first.

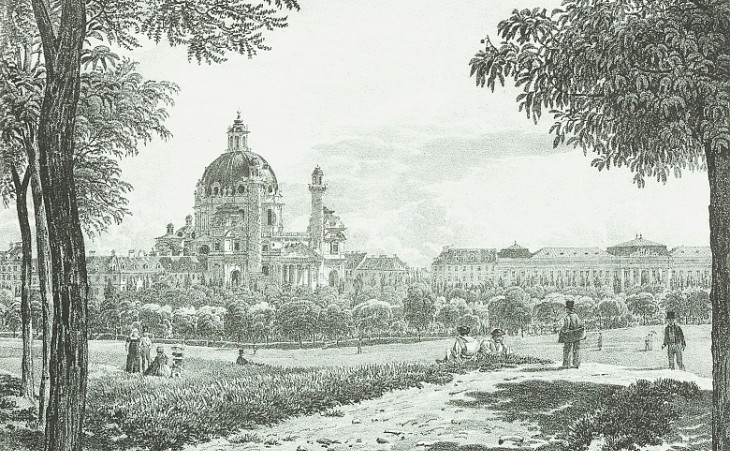

View of Karlskirche from the glacis which surrounded the walls until 1858 (ca 1820) - Wien Museum

The only church in the suburbs worthy of notice is that of St Carl, situated near the Rennweg, flanked on each side by two lofty columns, wound round with bas-reliefs representing events in the life of St Borromeo, which have somewhat the effect of the minarets of a mosque. It was built by the Emperor Charles VI in fulfilment of a vow made at a time when the plague was ravaging Vienna.

A Handbook for travellers in southern Germany by J. Murray - 1837

The intensity of cultural, religious and political links between Vienna and Rome is most evident

in Karlskirche, an imposing church commissioned by Emperor Charles VI to Johann Bernhard

Fischer von Erlach: the initial projects were submitted to the Emperor in 1715 and it was completed

in 1739, just one year before his death. So in a sense it could be regarded as the Emperor's

church.

Cardinal Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), nephew of Pope Pius IV, had a great role

in the reformation of the Catholic Church: he redesigned and clarified the responsibilities of parishes, bishoprics and departments of the Roman Curia. The dedication of the church was not without political and religious implications; there were

still significant pockets of Lutherans in some provinces of the empire, especially in Hungary. A dedication to a martyr, or an

apostle, or to a doctor of the early church would have been more acceptable to these subjects, but the Emperor wanted to underline

the strong link between his vision of the empire and the Catholic Church.

Another reason lay in the very recent acquisition of the Duchy of Milan, as a consequence of the 1713 Peace of Utrecht

at the end of the Spanish Succession War: Charles VI never entirely withdrew his claims

to the Spanish throne, but the compensation he received gave him a great influence on

Italian matters: Cardinal Charles Borromeo and his cousin Federico had been Archbishops of Milan and the Borromeo

were still a very important family, so the Emperor's choice was meant to please his new Italian subjects.

Saint Charles Borromeo was canonized for his activity during a pestilence which hit Milan in 1576. Vienna

was just getting over a similar scourge, so the dedication was justified also from a local point of view. The relief above the portico depicts the end of the pestilence.

Karlskirche: views of the dome: (left) frontal; (right) lateral

The dome has an elliptical shape so that in its frontal view one is struck by its vertical thrust and it resembles Roman domes by Pietro da Cortona and by walking around the church

the dome becomes more similar to that of S. Agnese in Agone.

The political objectives behind the erection of Karlskirche were not limited

to its dedication to Saint Charles Borromeo: the design of the church was meant to

enhance the role of Vienna as a new Rome, the capital of a great empire and at giving true significance to the title

Charles VI was most proud of: Imperator Romanus (or Romanorum). The portico and the two spiral columns were tributes

to monuments of Ancient Rome: the Pantheon and the columns of Trajan and of Marcus Aurelius.

Details of the columns: (left) relief depicting the funeral of Cardinal Borromeo; (right) tip of the column which is higher than those of the Roman columns and gives it an unwanted resemblance to an Ottoman minaret

Gian Lorenzo Bernini suggested to Pope Alexander VII to relocate Trajan's column to

Piazza Colonna (where he had just completed the Pope's family palace)

next to the other one. In 1694 Carlo Fontana developed a project for relocating the

column in nearby Piazza di Montecitorio and then merging the two squares;

so the idea of placing the two columns next to each other had been extensively debated in Rome.

Fischer von Erlach built on it, as if to show that Vienna could achieve what Rome had not been able to.

Karlskirche was built outside the walls at the assumed end of a long avenue

which should have linked Hofburg, the imperial palace,

with the new church; the two tall columns at the sides of the dome would have been the focal point of the avenue, similar to some obelisks in Rome. The avenue was never

opened and we cannot see the church in its entirety from a very long distance, as envisaged by its architect.

Karlskirche: details

Many details of Karlskirche lead to works by Bernini (the angels around the drum are similar to those at Ponte degli Angeli) or by Francesco Borromini (the shell decoration which resembles that at S. Carlo alle Quattro Fontane and the heads of angels utilized as architectural elements as at S. Giovanni in Laterano).

Main altar and detail of its upper part

The interior of the church is very bright with a decoration of white stucco and gold which characterizes many Roman churches and in particular il Ges¨; Fischer von Erlach, following the example set by Bernini in the Chair of St. Peter, placed a circle of angels, clouds and sun rays around a source of light in the apse.

Ceiling of the dome painted by Johann Michael Rottmayr: main scene: the Apotheosis of St. Charles Borromeo, a subject which was painted in the 1670s by Giacinto Brandi at SS. Carlo e Ambrogio

The elliptical dome was entirely frescoed by Johann Michael Rottmayr in 1726-1729, while the church was being completed; he chose to follow the pattern established by Andrea Pozzo at S. Ignazio and Jesuitenkirche, rather than that of il Baciccio at il Ges¨.

(left) Ceiling of the dome: Defeat of the Lutheran Heresy; (right) detail of True Faith triumphs over Heresy by Andrea Antonio and Giuseppe Orazi at S. Maria della Vittoria (ca 1700)

Rottmayr had to follow some religious guidelines in the minor episodes which he painted on the large ceiling; in one of them he had to portray an angel setting fire to the books written by Martin Luther, a subject which had already been painted in Roman churches.

(left-above) The Keys of St. Peter in the ceiling of Karlskirche; (left-below) the same subject in the ceiling of Sala del Trionfo at Palazzo Barberini by Pietro da Cortona; (right) Charity at Karlskirche

Parallels can be made between other details of the ceiling painted by Rottmayr and works of art in Rome (see a Charity by Antonio Raggi at S. Maria sopra Minerva).

Statues of St. Charles Borromeo on the fašade of Karlskirche (left) and on Kreuzerherrenhof, a late XIXth century building behind the church which was built for the Knights of the Red Star, a Bohemian military order similar to the Knights Hospitallers (right)

The image used as a background for this page shows the motto (Humilitas) of the Borromeo in the gardens of the family palace at Isola Bella.

Pages in this section of the website in recommended order:

Introduction: the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nations

Renaissance Vienna

The 1683 Siege of Vienna

XVIIth century churches

XVIIth century palaces

Monuments celebrating the end of plagues

The walls of Vienna

Sacred images

XVIIIth century churches

XVIIIth century palaces

Fountains

Italian cultural and artistic influence

A political manifesto: Karlskirche

Churches without the walls

Palaces and Villas without the walls

A day in the countryside: Perchtoldsdorf

in other sections of this website:

Vindobona, Roman Vienna

Belvedere Palace