All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in November 2025.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in November 2025.

Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

Museo dell'Opera del DuomoYou may wish to take a look at pages covering the exterior and the interior of the Cathedral first.

(left) Entrance to Museo dell'Opera del Duomo; (centre) a window of Duomo Nuovo, the unfinished enlargement of the Cathedral; (right) a capital inside the building

The image used as background for this page shows the inscription which characterizes all the buildings adjoining the Cathedral: OPA stands for OPerA (Work). Opera del Duomo, similar to Fabbrica di S. Pietro in Rome, was the body in charge of building the new Cathedral and ensuring its maintenance. After the project of building a larger cathedral was abandoned in 1355 the part which had been completed was turned into a building which sheltered the workshops and the offices of Opera del Duomo. Today it houses a large collection of statues and paintings from the Cathedral in addition to reliquaries and other ecclesiastical works of art. Some of them are illustrated in this page following a broad chronological order.

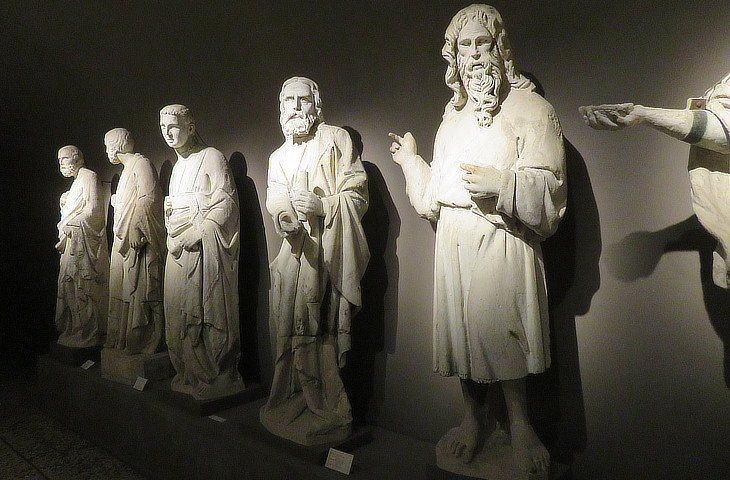

Statues of Apostles from the side of the Cathedral (School of Nicola Pisano)

The white marble which was used for the statues which decorate the exterior of the Cathedral and its adjoining facilities was quarried in the proximity of Siena and it did not stand the test of the time. In the second half of the XIXth century all the statues were replaced by copies and the originals were moved to Museo dell'Opera del Duomo.

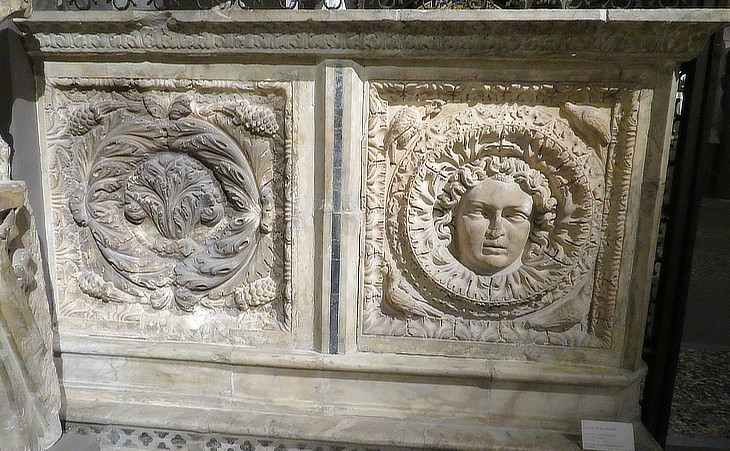

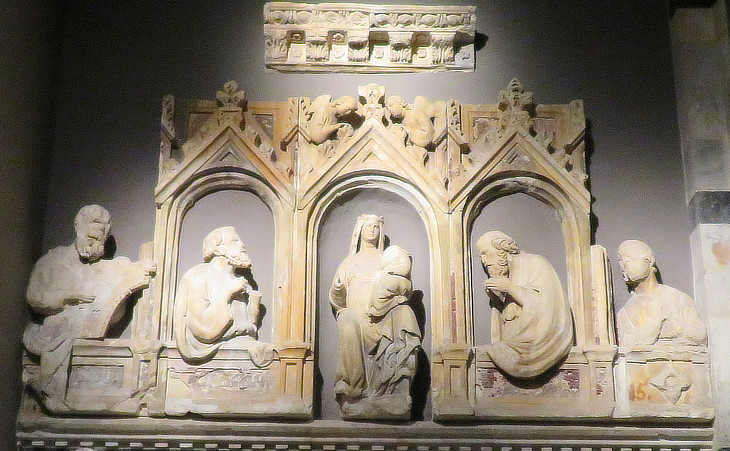

Panels from the presbyterial area of the Cathedral (School of Nicola Pisano)

Nicola Pisano was commissioned in 1266 the construction of a pulpit which is a masterpiece of the interior of the Cathedral. He also took care of the decoration of the presbyterial area which was modified in the following centuries. He had several assistants including his son Giovanni and Arnolfo di Cambio, who became the leading sculptor in Rome in the late XIIIth century (see his canopies at S. Paolo fuori le Mura and S. Cecilia).

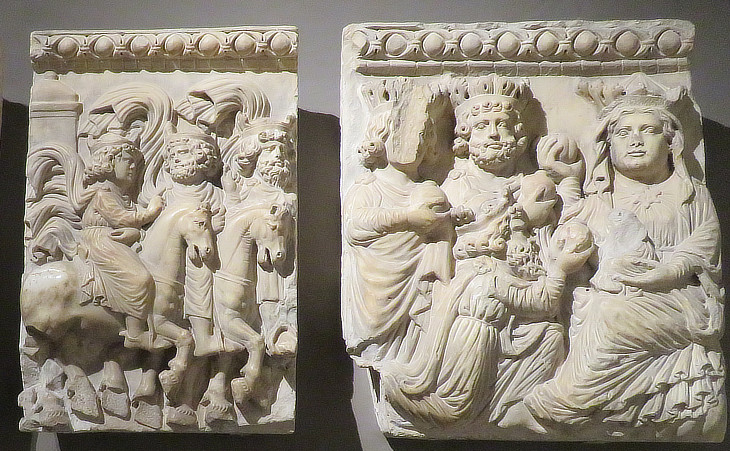

Reliefs portraying the Three Magi from S. Giovanni Battista a Ponte allo Spino, summer residence of the Bishop of Siena (early XIIIth century)

The bas-reliefs in the chapel of St. Ansano, in the Duomo at

Siena, which were brought from the Pieve al Ponte allo Spino, were probably sculptured early in the thirteenth century, by some one of the many artists then attached to the Duomo. They represent the Birth of Christ and the Adoration of the Magi, and show in their thick-set figures and clumsy style little knowledge of art, and little capacity for expression.

Charles C. Perkins - Tuscan Sculptors - 1864

She-wolf, the symbol of Siena which stood on a column near the fašade by Giovanni Pisano

The citizens of Siena claimed that their city was founded by Aschio and Senio, two sons of Remus, the brother of Romulus, the mythical founder of Rome. Fearing that their uncle wanted to kill them, Aschio and Senio escaped into Tuscany where they founded Siena carrying with them a statue of the she-wolf, the symbol of Rome; this explains why a she-wolf with two children became a symbol of the town. Two columns bearing this subject were erected at the sides of the Cathedral (see a relief at S. Caterina da Siena, the church of the citizens of Siena in Rome).

Animals from the fašade by Giovanni Pisano

The fašade is covered with ornaments and sculptures, among which are several animals symbolical of the cities which were allied to Siena at different periods during the struggles of the Guelphs and Ghibelines.

John Murray - Handbook for travellers in Central Italy - 1843

In addition to the symbols of other towns, the fašade was decorated with symbols of the Evangelists (the bull is one of them) and guardian lions which can be noticed in most Italian medieval churches, often in the act of tearing a lamb or holding a small human being (see those at S. Zeno in Verona). In general the animals attracted the curiosity of the viewers and were a test of the skill of the sculptor (see the bronze symbols of the Evangelists in the Cathedral of Orvieto).

Fragments of the columns at the side of the main portal by Giovanni Pisano (see those at the Baptistery of Pisa)

The great columns are finely engraven with fruits and foliage that run twitting about them from the very top to the bottom.

Joseph Addison - Remarks on several parts of Italy, in the years 1701, 1702, 1703

The columns are a unique reinvention of classical art. Their decoration is based on acanthus scrolls which are a common ancient decorative motif, but not typical of columns. Towards the end of the Ist century AD the scrolls began to be "inhabited" by birds and other small animals and eventually by Cupids performing farming activities (see a fragment of a lintel in Rome and another relief at Vaison).

Statues of Prophets by Giovanni Pisano and his assistants from the fašade: (left) Moses; (centre) King Solomon; (right) Jesus ben Sirach (a IInd century BC Jewish sage who is very rarely included among the prophets in Christian iconography)

The most remarkable sculptures of this front are the Prophets and the two Angels. Murray

After completing the Campo Santo of Pisa, Giovanni went to Siena, a.d. 1286. where he was appointed, as his father had been before him, to build the fašade of the Duomo. Hoping to induce him to settle in their city, the magistrates made him a citizen, exempted him from taxes for life, and, in order that he might continue to work without hindrance, absolved him from certain penalties to which he had for some unknown reason subjected himself. It is impossible to say exactly how far this work advanced under Giovanni's direction, during the three years of his residence at Siena, although it is clear that the fašade as it now exists is a modification of his original design by the architects who, after a considerable interval, succeeded him, and completed it in the next century. We can, however, safely ascribe its general features to Giovanni, since we trace in its combination of styles the influence of his father upon him, and see among the statues upon it some, which, if not his, must be by a sculptor bred in his school. Want of clearness, and a decidedly overloaded effect, produced by the particoloured marbles, the profusion of statues and bas-reliefs, mosaics, lions, horses and griffins, which cover every part of its surface, make it inferior to that of the Duomo at Orvieto, which belongs to about the same period, but, with all its defects, it is a splendid work. Perkins

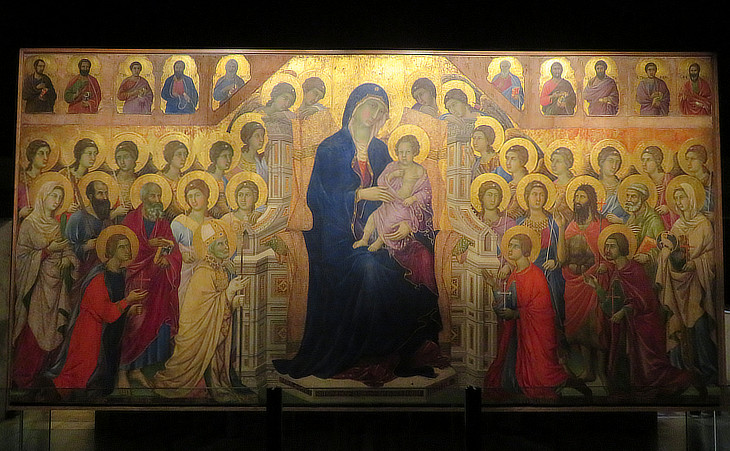

Front Side of the MaestÓ di Duccio di Buoninsegna

In the choir is a painting by Duccio di Buoninsegna, which is extremely interesting in the history of art; it is inscribed with his name, and was so highly prized at the period of its execution, that it was honoured with a public procession like that of Cimabue at Florence. It was originally painted on both sides; but these have been separated, and are both attached to the walls of the choir. One of these represents the Passion of Christ, and the other the Madonna and Child, with several Saints. Murray

(april 1790) Duccio of Siena began the picture for the high altar, and completed it in 1310, having received sixteen soldi a day for his labour. This picture now stands by the side of the altar St. Ansano, and is coloured on the back.

Richard Colt Hoare - A classical tour through Italy and Sicily - publ. in 1819

Front Side of the MaestÓ di Duccio: details showing a decoration based on Kufic calligraphy (see a relief with a similar decoration in a bronze door of S. Pietro in Rome

In the distribution of the principal scene of his altarpiece, in the prominent stature of the Virgin enthroned

in the midst of a triple row of angels and saints, Duccio preserved the order which was considered sacred at his

time. Transforming however, the art of his predecessors, he gave to the Virgin a regular shape and good

proportions. The drapery of her mantle is simple and well cast, and her attitude in the carriage of the Saviour

graceful and easy. The face of the latter is gentle,

plump, and regular, the forehead full and the short locks

curly. A small mouth and eyes no longer expressing

terror or immobility in their gaze, contrast favorably

with previous efforts at Sienna. The action of the infant

is natural and kindly. The group has more grace than

majesty or solemnity, and thus, from the very rise of the

school, its chief peculiarity was apparent.

J. A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle - A new history of painting in Italy - 1864

Pseudo-Kufic is a style of decoration used during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, consisting of imitations of the Arabic script, especially Kufic, made in a non-Arabic context. Pseudo-Kufic appears especially often in Renaissance art in depictions of people from the Holy Land, particularly the Virgin Mary. It is an example of Islamic influences on Western art.

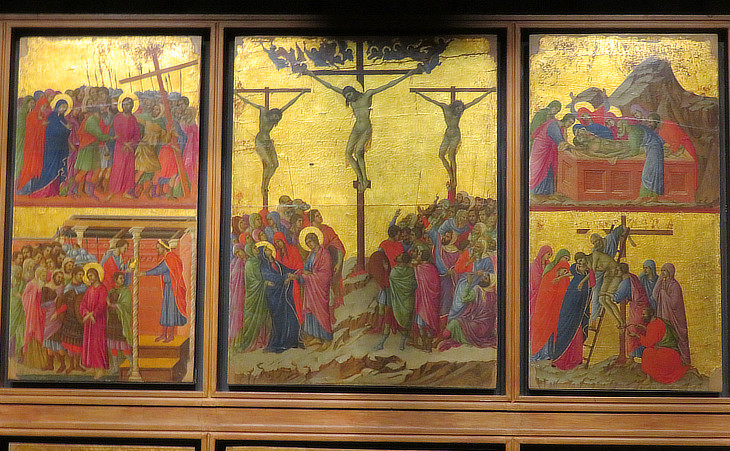

Rear Side of the MaestÓ di Duccio

Without doubt those who are inventors of anything notable receive the greatest attention from the pens of the writers of history, and this comes to pass because the first inventions are more observed and held in greater marvel, by reason of the delight that the novelty of the thing brings with it, than all the improvements made afterwards by any man whatsoever when works are brought to the height of perfection, for the reason that if a beginning were never given to anything, there would be no advance and improvement in the middle stages, and the end would not become excellent and of a marvellous beauty. Duccio, then, painter of Siena and much esteemed, deserved to carry off the palm from those who came many years after him, since in the pavement of the Duomo of Siena he made a beginning in marble for the inlaid work of the figures in chiaroscuro. (..) He made in the Duomo a panel that was then placed on the high-altar, and afterwards removed thence in order to place there the Tabernacle of the Body of Christ, which is seen there at the present day. In this panel, according to the description of Lorenzo di Bartolo Ghiberti, there was a Coronation of Our Lady, wrought, as it were, in the Greek manner, but blended considerably with the modern. And as it was painted both on the back part and on the front, the said high-altar being isolated right round, on the said back part there had been made by Duccio with much diligence all the principal stories of the New Testament, with very beautiful little figures. Vasari

Rear Side of the MaestÓ di Duccio: scenes from the Life of Jesus

Drawn in with excessive firmness, yet with the minutest care, the figures reveal in Duccio the cleanliness of a Dutchman, whilst the exquisite tracery of ornament and embroidery prove his taste and patience. (..) Duccio again gave to the twenty six scenes of the Passion, forming originally the reverse of the altarpiece, a clear impression of life and power, and displayed talents of a first rate order, but, had he not exhibited in the composition, form, action and character of the persons represented, the exaggeration peculiar to the old schools, he would have been greater. It was not within the scope of his genius, however, to preserve a simple or equal grandeur. Like all those whom he followed or preceded, he had no great mean to guide him, and the decorous simplicity of the Florentines was out of his character. In the manuscripts of the twelfth and previous centuries, in the subordinate scenes which explain or develop the interest of the crucifixions in early times, in the mosaics of Monreale or the bronze gates of Ravello and S. Raineri at Pisa, the typical compositions which Duccio reproduced are to be found, and thus the leading genius of the school of Sienna clung to the traditions which Florence rejected or altered. Crowe and Cavalcaselle

Stained glass window of the apse painted by Duccio (see that of the fašade)

The Cathedral is dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and the stained glass window of the apse depicts her Burial, her Assumption and her Coronation. The Four Evangelists and the Four Patron Saints of Siena are portrayed at the sides of these scenes. The window was dismantled in 1943 to protect it from war damage and at a close examination art historians attributed it to the hand of Duccio. The Coronation of Mary is very similar to the same subject in the 1295 mosaic of the apse of S. Maria Maggiore in Rome by Jacopo Torriti.

Statues of Portale di Vallepiatta, side portal of Duomo Nuovo by Giovanni di Agostino (ca 1348)

Giovanni di Agostino was the son of Agostino di Giovanni and he assisted his father in the construction of the Monument to Bishop Guido Tarlati at Arezzo. In 1340-1348 he was involved in the construction of Duomo Nuovo where he designed a fine portal with a statue of Jesus between two kneeling angels.

Reliefs from the upper part of the fašade, most likely by Giovanni di Cecco

Among the many sculptors who lived at Siena during the fourteenth century, few attained celebrity, especially during its latter half, which was marked by intestine quarrels, ending in the exile of many of the most able artists, which reduced art, in all its branches, to a very low ebb. Perkins

Giovanni di Cecco, a sculptor, appears to have taken over direction of the completion of the fašade in the mid XIVth century but the date is uncertain.

Polyptych by Ambrogio Lorenzetti: St. Benedict, St. Mary Magdalene, St. Catherine and St. Francis (ca 1333)

The School of Siena is so remarkable a feature in the history of the city, that it will be desirable to give a brief epitome of its character and its masters, in order that the works of art scattered over its churches and palaces may be the more thoroughly appreciated. The prevailing characteristics of this school are deep religious feeling, and a peculiar beauty and tenderness of expression inspired by devotional enthusiasm, differing altogether from that style which classical study had introduced into the northern schools of Italy. In antiquity the Sienese school is nearly equal to that of Florence, and there is no doubt that it exercised an important influence on the great masters of the fifteenth century. The patronage of the republic as early as the thirteenth encouraged if it did not create a society of artists, of which Guiduccio, Diotisalvi, Guido da Siena, and Duccio di Buoninsegna were the leading members. The most remarkable among the early masters is Simone Memmi, or rather Simone di Martino, the contemporary of Giotto and friend of Petrarch. He died in 1344; among his scholars were his relative Lippo Memmi, and Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Murray

The Lorenzetti, who followed Duccio, acquired some of the practice of the Florentines, and infused into their grand and admirable works some of the spirit of Giotto. (..) A Florentine altarpiece might compel attention at a distance: a Sienese panel required close inspection; but, for this very cause, it demanded more minute finish and more hours of labour. Crowe and Cavalcaselle

The polyptych is no doubt a lavoro di bottega, a routine painting which was mainly executed by assistants. The frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti at Palazzo Pubblico are instead very innovative and testify to his talent and skill.

Painted wooden statues by Jacopo della Quercia (1415-1420): (left) St. John the Baptist; (right) Madonna between St. Bartholomew and St. John the Baptist

Indeed, the Sienese school of sculpture seemed dying out altogether, when Giacomo della Quercia, who was to give it new life, was born at Siena in 1371. (..) While resident at Ferrara, Quercia was appointed by the Signory of Siena to make a fountain for the great piazza of their city (Fonte Gaia). (..) Quercia was neither a purist nor a classical sculptor; he wanted the delicate refinement and elegance of the great Florentine masters, and concealed his defects by a richness of drapery and voluptuousness of form which sometimes trenched upon coarseness. Perkins

(left) Relief by Jacopo della Quercia portraying Cardinal Antonio Casini at the feet of the Virgin Mary and St. Anthony the Abbot watching the scene (1438 from the Chapel of St. Sebastian); (right) holy water font by Antonio Federighi a pupil of della Quercia (still in the Cathedral)

The Cardinal asked the sculptor to carve his figure the same size of as the saint, thus displaying arrogance and pride, because donors were always portrayed at a smaller scale. Cardinal Casini lived in a very troubled period of the history of the Roman Church. He was appointed Bishop of Siena by Pope Gregory XII in 1408, but in 1413 he is recorded as Treasurer of Antipope John XXIII. He was eventually confirmed in this position by Pope Martin V who created him cardinal in 1426.

Of the two vases for holy water, one is an ancient candelabrum, covered with mythological sculptures; the other is an able work of Jacopo della Quercia. Murray

The font is now assigned to Antonio Federighi.

A polyptych from the altar of the Tolomei chapel by Gregorio di Cecco di Luca (1423)

The Tolomei were one of the richest family of Siena. The altarpiece in their family chapel in the Cathedral still clings to the tradition of the XIVth century school of Siena. The side panels which portray St. Augustine, St. John the Baptist, St. Peter and St. Paul (and above them the Four Evangelists) are almost identical to those made a century earlier by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. The only novelty is the depiction of a Madonna del Latte (Nursing Madonna) surrounded by angels playing a variety of musical instruments. These depictions became very common in the XVth century and they testify to the increased use of music in religious ceremonies (see a fresco by Filippino Lippi in a page covering this subject).

Altarpieces by Matteo di Giovanni: (left) Madonna and Saints (Cathedral 1480 - the image shows St. Gregory the Great); (right) Madonna between St. Anthony and St. Bernardine of Siena (Baptistery 1460)

Florence in the fifteenth century gave more in quality if less in quantity, and towered then as ever over all Italy; and if she found in Sienna a rival in the fourteenth, she left her behind in the next age. Crowe and Cavalcaselle

XVth century Sienese painting still charms with its surviving line traditional qualities - its sincerity of feeling, the refined grace of its figures, its attention to minutiae of dress and of architectural background, and its fascinating frankness of execution. Of these qualities Matteo di Giovanni has his share and he is regarded as one of the best Sienese painters of that century.

Gaston Sortais - Catholic Encycloaedia - 1913

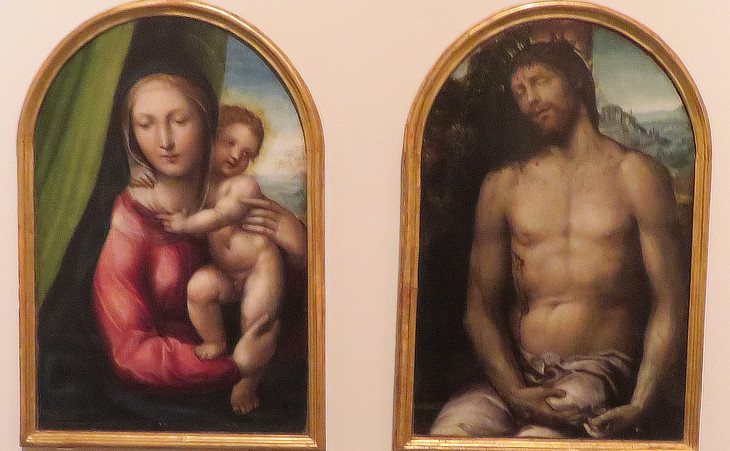

Small paintings by il Sodoma (1526) for Compagnia della Morte, a brotherhood whose members gave assistance to those who were sentenced to death; the brotherhood had an oratory near the Cathedral (see Sodoma's frescoes at S. Domenico)

The Sienese school did not recover its character until the introduction of the modern style. The most eminent artist of this period was Gianantonio Razzi, better known as Sodoma, a follower and perhaps a pupil of Leonardo da Vinci, whose merits were so great that he was employed on the decorations of the Vatican and the Farnesina Palace. Murray

These small paintings decorated the cataletti of the brotherhood, i.e. decorated stretchers which were used for the funerals. The brotherhood was suppressed in the late XVIIIth century.

Reliquary of St. Galgano and details of its decoration (see another reliquary of the School of Siena at Viterbo)

During the thirteenth century, Siena gave abundant employment to her architects and sculptors in the enlargement of her Duomo, the construction of the abbey church and monastery of S. Galgano, and in the building of walls and fortifications, bridges, gates, and fountains. Perkins

The Abbey of St. Galgano was a Cistercian Monastery founded between Siena and Massa Marittima, on the site where Galgano, a knight who became a hermit, died in 1181. According to the documents of his canonization in 1185, while on the road near Siena, his horse threw him into the dust and he had the vision of an angel who invited him to repent of his sins. Galgano replied that he could no more do this than to split a rock with a sword. To prove his point, he drew his blade and thrust it at the stony ground, but the sword slid easily into the rock. The monastery of St. Galgano was abandoned in the XVIth century and today only the roofless walls of the Abbey church still stand.

The reliquary is a true masterpiece of Sienese goldsmithing of the XIVth century. It is made up of copper, gilded silver, embossed, chiselled and translucent enamels, which depict episodes from the life of St. Galgano, including the episode of the sword thrust into the rock. The reliquary, originally at the monastery, was kept in a seminary near Siena from which it was stolen in 1989. It was recovered in 2021 and then carefully restored by Vatican Museums experts before being returned in all its splendour to the Archdiocese of Siena.

Details of the pastoral staff of St. Galgano (ca 1317)

This very elaborate staff portrays six couples of saints in a sort of hexagonal Gothic building. Above it angels are depicted inside Gothic niches. The curl of the staff has an elaborate decoration of small enamels depicting flowers or birds and it ends with a statue of Galgano praying in front of his sword in the rock which forms a cross.

Golden Rose, a gift by Pope Alexander VII designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1658; the six mountains are the heraldic symbol of the Pope

Move to:

From Porta Camollia to S. Domenico

Piazza del Campo

Cathedral - Exterior

Cathedral - Interior

S. Maria della Scala.