All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in September 2025.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page added in September 2025.

Volterra - The Ancient Town

Volterra - The Ancient TownFor an introduction to Maremma and a map of the region you may wish to read this page first.

S. Francesco: modern terracotta decoration of the portal showing at the sides of the Madonna, the "must see" of Volterra: the Baptistery, the Cathedral, Palazzo dei Priori, a medieval tower and Arco Etrusco

Twenty three miles south of Florence, stands the city of Volterra. This is a very ancient city, as appears by some statues still remaining. It is built on a hill near the river Cecina, where there are several fine stone quarries, and springs of mineral waters. The town is a bishop's see.

Thomas Nugent - The Grand Tour - 1749

From Poggibonsi the traveller may make an interesting excursion to Volterra, distant about twenty miles. There is a more level but longer road from Florence through Empoli and Pontedera: but those who have had no previous opportunity of visiting Volterra should devote a day or two to the excursion to this place. (..) It is one of the most interesting towns in Italy, and travellers who are desirous of investigating the remains of one of the ancient Etruscan cities should on no account lose an opportunity of visiting it.

John Murray - Handbook for travellers in Central Italy - 1843

April 20, 1790. After dinner I left Colle, and took leave of my carriage. The environs are well cultivated; but as I proceeded, the country became wild, woody, and barren. The road in general is ill paved, and very hilly. To Volterra the ascent is long and steep. I was five hours on my journey, in consequence of the badness of the road, the slowness with which I was obliged to travel on account of my baggage horse, and a violent thunder storm which caught me on my route.

Volterra, in point of situation, is perhaps the most elevated town of residence in Italy (531 m - 1,742 ft). It occupies a species of plain, on the summit of a mountain. This was likewise the site of the ancient town, which is accurately described by Strabo. There was, however, a great variation as to size; for the ancient walls embraced a circuit of seven miles while the modern comprise but three.

Richard Colt Hoare - A classical tour through Italy and Sicily - publ. in 1819

From whatever side Volterra may be approached it is a most commanding object, crowning the summit of a lofty, steep, and sternly naked height, if not wholly isolated, yet independent of the neighbouring hills, reducing them by its towering supereminence to mere satellites; so lofty as to be conspicuous from many a league distant, and so steep that when the traveller has at length reached its foot, he finds that the fatigue he imagined had well nigh terminated, is then but about to begin. Strabo has accurately described it when he said "it is built on a lofty height, rising from a deep valley and precipitous on every side, on whose level summit stand the fortifications of the city. The ascent is fifteen stadia long, and it is steep and difficult throughout." (..) At my feet lay an expanse of bare undulating country, the valley of the Era, broken into ravines and studded with villages.

George Dennis -

The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria - 1848 Ed.

It is surrounded by smaller hills of similar formation, whose soft porous soil is so frequently washed away by the rains and torrents, that the neighbouring country presents a singular appearance of wild and sterile desolation. (..) In spite of the dreary aspect of the country, the view from the summit of the hill, and especially from the citadel, is particularly striking. (..) The population of the town is 4500. Murray

After the fall of the Western Empire, Volterra suffered the fate of the neighbouring cities, and fell under the dominion of the Vandals and the Huns; but was again raised to importance by the Lombard kings, who, for a time, fixed their court here, on account of the natural strength of the site. Of the subsequent history of Volterra, suffice it to say, that though greatly sunk in size and importance, she has never wholly lost her population, and been abandoned, like so many of her fellows, to the fox, the owl, and the viper; and that she retains to the present day, her original Etruscan appellation, but little corrupted. Dennis

During the middle ages, its strong position in the midst of the Maremma*, between the republics of Pisa, Florence, and Siena, naturally made it a place of great importance in the contests of the free cities. Like many other small towns of central Italy, it was for some time able to assert its independence, and was governed by its own consuls; but it, gradually fell under the power of Florence, and from that time its history is to be traced in that of the Florentine republic. Murray

* Today Volterra is regarded as being immediately outside Maremma, but Emanuele Repetti, an erudite who published the Dizionario geografico, fisico e storico della Toscana (1833-1846), which offers an account of the natural and civic history of municipalities in Tuscany, included the town in Maremma.

Dante - Purgatorio, Canto V

"Deh, quando tu sarai tornato al mondo, "ricorditi di me che son la Pia: | Translation by H. W. Longfellow Ah, when thou hast returned unto the world,

"Do thou remember me who am the Pia; |

Where exactly Pia de' Tolomei died and why is still a matter of debate.

In those huge Stones which lie scattered in some places about the Town of Volterra (being the remainders of antient Walls) there are found all sorts of Shells, and not long since in the middle of the Market-place there was cut out a Stone full of streaked Cochles.

John Ray's Observations topographical, etc.: in a journey through (..) Italy; published in 1673.

Near St. Giusto are seen the remains of the ancient church of the same name, which fell to ruin by the sinking of the ground. Similar phenomena are daily seen at a place called Le Balze (It. balzo - jump). Colt Hoare

The town is situated on a lofty and commanding eminence, capped by a tertiary sandstone full of marine shells, which rests upon a bed of white clay 200 or 300 feet thick. (..) In the immediate neighbourhood one of the most remarkable objects is the deep chasm called the Balze, produced by the action of water during many centuries on the soft porous soil of the surrounding hills. There is no place in Tuscany where the operation of this cause has been attended with more disastrous consequences. (..) Large portions of the rock are continually falling from the summit, without having any apparent effect in filling up the abyss. It is known from authentic documents that the ravine in the seventh century was a highly cultivated spot, well wooded, and covered with habitations; about the end of the 16th century the sides were observed to be gradually undermined by the water which had penetrated through the porous strata; in 1627 it engulfed the church of San Giusto; and in 1651 its rapid increase compelled the removal of another church, which had previously appeared beyond the reach of danger. (..) The inhabitants observe with great regret that the danger is gradually approaching the ancient Etruscan walls on this side. The probable cause of the continued voracity of this chasm seems to be a subterranean stream or river, which having at this point crossed a vast bed of salt which underlies this country, has worked out the excavation, and continually removes the clay and rocks which fall into it. Murray

The landscape took on something of an infernal aspect; a prospect of parched hills and waterless gulleys, like the undulations of a petrified ocean, expanded interminably round them. And on the crest of the highest wave, the capital of this strange hell, stood Volterra - three towers against the sky, a dome, a line of impregnable walls, and outside the walls, still outside, but advancing ineluctably year by year towards them, the ravening gulf that eats its way into the flank of the hill, devouring the works of civilization after civilization, the tombs of the Etruscans, Roman villas, abbeys and mediaeval fortresses, renaissance churches and the houses of yesterday.

A. L. Huxley - Those Barren Leaves - 1925

Here we sit on the ancient heaps of masonry and look into weird yawning gulfs, like vast quarries. The swallows, turning their blue backs, skim away from the ancient lips and over the really dizzy depths, in the yellow light of evening, catching the upward gusts of wind, and flickering aside like lost fragments of life, truly frightening above those ghastly hollows. The lower depths are dark grey, ashy in colour, and in part wet, and the whole thing looks new, as if it were some enormous quarry all slipping down.

This place is called Le Balze - the cliffs. (..) Across the gulf, away from the town, stands a big, old, picturesque, isolated building, the Badia or Monastery of the Camaldolesi, sad-looking, destined at last to be devoured by Le Balze, its old walls already splitting and yielding.

David Herbert Lawrence - Etruscan Places - Published in 1932, but based on a visit made in April 1927.

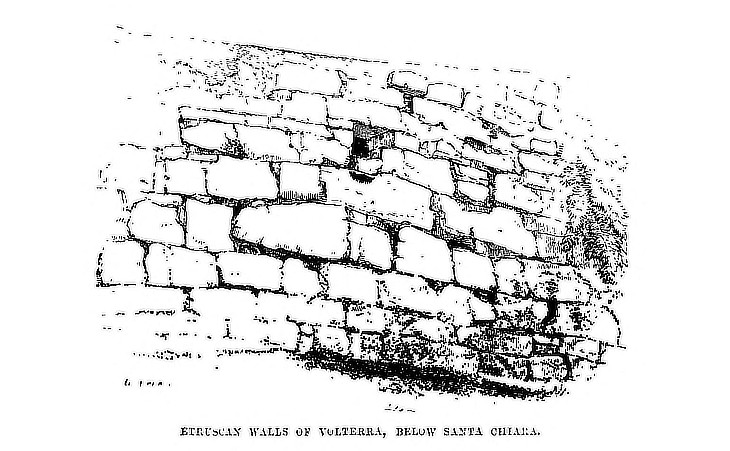

Etruscan Walls below S. Chiara from Dennis' book

Although a considerable difference of opinion has existed among antiquaries respecting the twelve towns of Etruria, Volterra has been generally estimated as one. The place it occupies in history, and the numerous fragments of antiquity found in its neighbourhood, authenticated by Etruscan characters, admit little doubt respecting its right to this distinction. Colt Hoare

Her great size and the natural strength of her position mark Volaterrae as a city of first-rate importance, and give her indisputable claims to rank among the Twelve of the Confederation. (..) From the Porta all'Arco let the visitor continue his walk eastward, beneath the walls of the modern town, till, leaving these behind, and following the brow of the hill for some distance, he comes in sight of the church of Sta. Chiara. Below this are some of the finest portions of the ancient walls now extant. They are in detached fragments. (..) The masonry is very irregular. A horizontal arrangement is preserved, but one course often runs into another, shallow ones alternate with deep, or even in the same, several shallow blocks are piled up to equal the depth of the larger. The masses, though intended to be rectangular, are rudely hewn, and more rudely put together. (..) This may be called a rectangular Cyclopean style, if that be not a contradiction of terms. Dennis

Volterra is more easily accessible, and retains more of its ancient character than any other Etruscan settlement; and those who have thoroughly investigated its antiquities will find that they have little to learn respecting the habits and customs of ancient Etruria, which may be acquired in the museums of the great capitals. Murray

I envy the stranger his first impressions on approaching this gateway. The loftiness of the arch; the boldness of its span; the massiveness of the blocks, dwarfing into insignificance the mediaeval masonry by which it is surrounded; the venerable, yet solid air of the whole; and more than all, the dark, featureless, mysterious heads around it, stretching forward as if eager to proclaim the tale of bygone races and events; even the site of the gate on the very verge of the steep, with a glorious map of valley, river, plain, mountain, sea, headland, and island, unrolled beneath; make it one of the most imposing yet singular portals conceivable, and fix it indelibly on the memory. (..) Whether this archway be Etruscan or not, it cannot be doubted that the three heads are of that character, and that they occupied similar positions in an arched gateway of ancient Volterra. This is corroborated in a singular manner. In the Museum is a cinerary urn, found in this necropolis, which has a bas-relief of the death of Capaneus, struck by lightning when in the act of scaling the gate of Thebes; and the artist, copying probably the object best known to him, has represented in that mythical gate, this very Porta all'Arco of Volterra, with the three heads exactly in the same relative position. What the heads might mean is not easy to determine. They may represent the heads of conquered enemies or possibly the patron deities of the city. Dennis

One of the ancient gates is still standing, in a fine state of preservation. It is called the Porta all'Arco, and is a circular arch, formed of nineteen immense masses, put together without cement, and beautifully worked on the exterior face. The keystone and the two pilasters have three colossal heads sculptured in the stone, which were formerly supposed to be lions; but a bas-relief of one of the cinerary urns in the Museum, which appears to represent this gate, shows that they were human heads. Murray

The modern town is not very large. We went down a long, stony street, and out of the Porta dell' Arco, the famous old Etruscan gate. It is a deep old gateway, almost a tunnel, with the outer arch facing the desolate country on the skew, built at an angle to the old road, to catch the approaching enemy on his right side, where the shield did not cover him (a defensive measure which can be noticed also in other ancient towns, e.g. Ferentino). Up handsome and round goes the arch, at a good height, and with that peculiar weighty richness of ancient things ; and three dark heads, now worn featureless, reach out curiously and inquiringly, one from the keystone of the arch, one from each of the arch bases, to gaze from the city and into the steep hollow of the world beyond. Strange, dark old Etruscan heads of the city gate, even now they are featureless they still have a peculiar, out-reaching life of their own. (..) And the archaeologists say that only the doorposts of the outer arch, and the inner walls, are Etruscan work. The Romans restored the arch, and set the heads back in their old positions. While the wall above the arch is merely mediaeval. But we'll call it Etruscan still. The roots of the gate, and the dark heads, these they cannot take away from the Etruscans. And the heads are still on the watch. Lawrence

Of the few remains of Etruscan architecture the most remarkable are, the Porta dell'Arco, the Piscina and the walls, which are still easily traced. The Piscina is supposed to have been originally a reservoir of water. (..) From the present fortress I descended through different apertures to the Piscina. It is divided into three apartments, and is the most perfect specimen of Etruscan workmanship now existing at Volterra. Exact measurements of it are given in a work lately published, by the Abbate Giachi. Colt Hoare

Outside the gate of the fortress, but within the walls of the town, is the so-called Piscina. Like all the structures of similar name elsewhere in Italy, this is underground - a series of parallel vaults of great depth, supported by square pillars, and evidently either a reservoir for water, or, as the name it has received implies, a preserve for fish - more probably the former. The vaults are arched over, but the pillars are connected by flat architraves, composed of cuneiform blocks, holding together on the arch principle. There is nothing in this peculiar construction which is un-Etruscan; but the general character of the structure, strongly resembling other buildings of this kind of undoubtedly Roman origin, proves this to have no higher antiquity. Gori, however, who was the first to descend into it, in 1739, braving the snakes with which tradition had filled it, declared it to be of Etruscan construct, an opinion which has been commonly followed, even to the present day. He who has seen the Piscine of Campanian coast (see a Roman cistern at Formia), may well avoid the difficulties attending a descent into this. A formal application has to be made to the Bishop, who keeps the key; a ladder of unusual length has next to be sought, there being no steps to descend; the Bishop's servant, and the men who bring the ladder, have to be fed so that those who consider time, trouble, and expense, "le jeu ne vaut pas la chandelle". Dennis

(left) Modern Etruscan-style wall supporting the site of the ancient acropolis; (right) Parco Enrico Fiumi, a local archaeologist, on the site of the acropolis

The great wall of the Etruscan city swept round the south and eastern bluff, on the crest of steeps and cliffs, turned north and crossed the first finger, or peninsula, then started up hill and down dale over the fingers and into the declivities, a wild and fierce sort of way, hemming in the great crest. The modern town occupies merely the highest bit of the Etruscan city site.

The walls themselves are not much to look at, when you climb down. They are only fragments, now, huge fragments of embankment, rather than wall, built of uncemented square masonry, in the grim, sad sort of stone. One only feels, for some reason, depressed. And it is pleasant to look at the lover and his lass going along the top of the ramparts, which are now olive-orchards, away from the town. At least they are alive and cheerful and quick. Lawrence

A series of excavations (in 1967-1972 and after 1987) on the hill where the Piscina is located brought to light the remains of the main religious buildings of the Etruscan city. The area was turned into a pleasant garden where some scanty evidence of the foundations of temples can be noticed. The wall supporting the garden was rebuilt to give an idea of the appearance of those of the Etruscan town.

The stone remains are those of various constructions that have followed one another since the VIIth century B.C. until the Roman age. Of the monuments that were found on the acropolis the oldest one was a temple of which, however, nothing has remained visible, being built mainly in clay and wood. The remains visible today are those of two large sanctuaries built in the Hellenistic period, around the IIIrd century BC. In addition to these, the foundations of various service buildings, some cisterns and paved roads also survived, which can also be dated to the Hellenistic age.

A new temple provided with a complex of precincts arranged in series on its front replaced the late archaic temple. These open spaces were used for ceremonies. The construction of a second temple alongside the previous one but different in size, façade orientation and plan completed the building program in the IInd century BC. Another small building dedicated to Demeter at the southern end of the plateau closed the sacred area. Subsequently, the sanctuary does not seem to have been modified. Worship continued until the IIIrd century AD. You may wish to see the monumental Shrine of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina, south of Rome.

We have no record of her conquest, but from her remoteness and strength we may conclude Volaterrae was among the last of the cities of Etruria to fall under the yoke of Rome. In the Second Punic War, in common with the other principal cities of Etruria, she undertook to furnish her quota of supplies for the Roman fleet; and it is worthy of remark that she still maintained her maritime character, being the only one, save Tarquinii, to furnish tackling or other gear for ships. In the civil wars between Marius and Sylla, Volaterrae, like most of the cities of Etruria, espoused the part of the former; for this she was besieged two years by the forces of his rival, till she was compelled to surrender though she escaped the fate of Faesulae and other cities which were deprived of their citizenship, and had their lands confiscated and divided among the troops of the victorious Dictator. Dennis

Near the Florence gate some traces of the amphitheatre have been discovered. Murray

Within the ancient walls are the remains of two structures which have often been called Etruscan - the Amphitheatre and the Piscina. The first lies in the Valle Buona, beneath the modern walls, to the north. Nothing is now to be seen beyond a semicircle of seats, apparently cut in the slope of the hill and now covered with turf. It displays not a trace of antiquity, and seems to have been formed for no other purpose than that it is now applied to - witnessing the game of the pallone. One may well doubt if it has ever been more than a theatre, for the other half of the structure, which must have been of masonry, has totally disappeared. Its antiquity, however, has been well ascertained, and it has even been regarded as an Etruscan structure, but more discriminating criticism pronounces it to be Roman. Dennis

Excavations carried out in the 1950s uncovered the site of a Roman theatre which was built at the time of Emperor Augustus. It was partially built into the natural slope of the hill and excavations brought to light some limestone seats bearing the names of wealthy families of Volterra. It is located just outside the Porta Fiorentina, in an area called Vallebuona. The part of the two-story scenae frons that is standing today was reconstructed in the late 1970s. The theatre fell into disuse in the IIIrd century. Its premises included a square portico inside which a small bath establishment was built at the end of the IIIrd century.

The interest of the urns of Volterra lies rather in their reliefs than in their inscriptions. Some, however, have this additional interest. It has already been said that this Museum contains the urns found in the tomb of the Caecinae, that ancient and noble family of Volterra, which either gave its name to, or received it from, the river which washes the southern base of the hill, a family to which belong two "most noble men" of the name of Aulus Caecina, the friends of Cicero; the elder defended by his eloquence; the younger honoured by his correspondence. (..) It also occurs in its Latin form on other monuments. (..) Others of the Caecinae distinguished themselves under the Empire in the field, in the senate, or in letters. This family has continued to exist from the days of the Etruscans, almost down to our times; though it now appears to be extinct. Dennis

The construction of the theatre was financed by members of the wealthy Caecina family of Volterra. The inscription lists Gaius Caecina Largus and Aulus Caecina Severus (consul 2-1 BC) as dedicators.

Move to

Museo Etrusco Guarnacci

The Medieval Town

Churches and Paintings

In Maremma - other pages:

Corneto (Tarquinia)

Corneto (Tarquinia) - Palazzo Vitelleschi and Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Tarquinia

Tarquinia - Etruscan Necropolis of Monterozzi

Montalto di Castro and Canino

An Excursion to Orbetello

An Excursion to Porto Ercole

An Excursion to Grosseto

An Excursion to Massa Marittima