All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in December 2020. The text and the images are based on a visit made in October 2010. They do not reflect the impact of the civil war.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in December 2020. The text and the images are based on a visit made in October 2010. They do not reflect the impact of the civil war.

- Sabratha: Baths and Theatre

- Sabratha: Baths and TheatreSabratha was one of the ports of Roman Tripolis which had strong business ties with Ostia, the port of Rome; in both towns the main baths were located near the Forum (see the Forum of Sabratha in page one).

The baths were built on the edge of a cliff having a commanding view over the sea; the construction technique adopted by local engineers relied more on blocks of sandstone (which were quarried in the vicinity of the town) rather than on masonry; this may explain why vaults and pillars have not survived to our time, unlike those of some baths in Rome, e.g. Terme di Diocleziano.

There are still more questions than answers on the social role of toilets in the Roman world. The marbles and columns which decorated the toilets at Sabratha (and the view!) indicate that people did not pay a cursory visit to these facilities, but sat and chatted, without feeling uncomfortable about the lack of privacy (the similarity with the toilets at Ostia is striking).

Baths by the sea: mosaics and in the background: Temple to Isis (far left) and the theatre (far right)

The baths were decorated with coloured mosaics with a variety of geometric patterns; a recurring motif throughout the whole Roman Empire was based on peltae, the shields of the Amazons (you may wish to see a pelta in a relief in the Museum of Corinth or a fountain showing four peltae in Domus Augustana, the imperial palace in Rome).

Solomon's knot was another popular decorative motif which can be seen in the image above; it is found in many ancient synagogues, but also in non Jewish buildings (see the Solomon's knots in the Synagogue of Sardis and those in a Roman villa in Spain).

When storms threaten their lives seamen from Genoa and Marseille trust their safety to statues of the Virgin Mary which are housed in sanctuaries near their hometowns which are visible from a great distance; the seamen of Sabratha did the same with Isis, an Egyptian goddess which in the Greek-Roman world received the epithet of Stella Maris (Star of the Sea); the Temple to Isis at Sabratha stood on an isolated cliff so that it could be easily identified; ceremonies were held in spring on the expanse of water near the temple to celebrate the beginning of the sailing season.

The conquest of Libya in 1911-1912 was justified by the Italian government of the time with the need for providing the population of the country with new work opportunities (Italy had extremely high emigration rates); after WWI the Fascist regime placed the Italian presence in Libya into a different context: that of reviving the ancient Roman Empire. Although Italian archaeologists had a conservative approach to the reconstruction of ancient monuments, at Sabratha they were subject to political pressure and, in order to make visible the heritage of Rome in the region, they reconstructed major parts of the town's large theatre.

Theatre: reconstructed "proscaenium", the decorated wall behind the scene

The theatre was built in 175-200 AD, so it was started by Emperor Marcus Aurelius; the construction was continued by his son Commodus and completed with a lavish proscaenium by Emperor Septimius Severus who was born in Leptis Magna; this time frame is applicable also to the enlargement of the theatre of Ostia. You may wish to see the Roman theatre of Bosra in Syria which retains its original backstage.

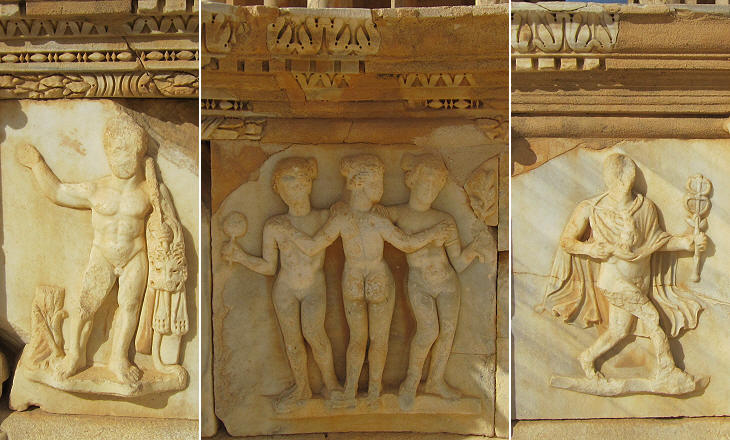

Reliefs portraying Hercules (left), the three Graces (centre) and Hermes (right)

The area which best survived to our time is the base of the stage which was decorated with reliefs portraying gods and scenes from comedies and dances; the image used as background for this page shows a relief portraying Paris being asked by Hermes which of three goddesses was the fairest (see a page on Roman works of art related to theatrical performances).

Italian archaeologists unearthed a private villa near the theatre; its courtyard was surrounded by columns (peristilium means columns around); among the fine mosaics which decorated the floor of its halls, one depicts a maze, the Cretan Labyrinth. You may wish to see a similar mosaic at Italica in Spain.

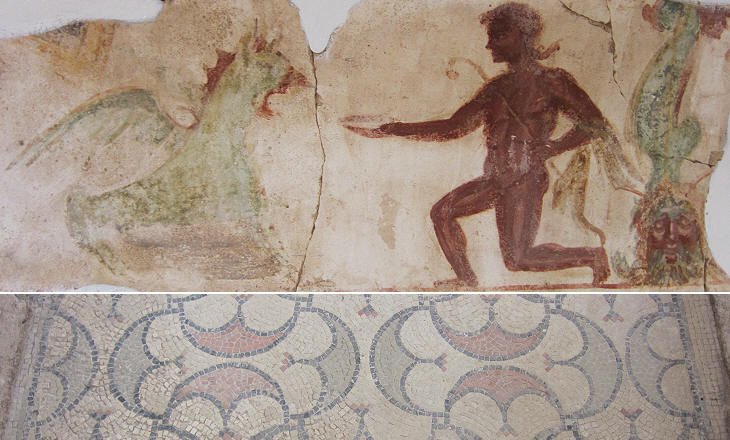

Museum of Sabratha: (above) The Riddle of the Sphinx; (below) floor mosaic decorated with a motif based on "pelta", the Amazons' shields

The Museum of Sabratha has a large selection of mosaics, paintings, statues and reliefs found in private houses and villas; the prevailing subjects are linked to the Greek myth, an effect of the Romanization of the region, which in origin had a Phoenician culture.

Museum of Sabratha: Leda and the Swan from the House of Leda

The union of Leda with Zeus in the form of a swan was a subject which led to depicting a scene which in today's world would fall into the category of soft porn; this relaxed approach to sex was common to all parts of the Roman Empire (see a statue of Leda at Dion in Greece).

Museum of Sabratha: (left) Fall; (right) Orpheus taming the animals by playing the lyre (see a mosaic in Syria and one in France)

An explanation for the repetitiveness of some subjects in works of art throughout the Roman Empire is that they were manufactured in one location and then shipped as a luxury item; Afrodisia, a town in Asia Minor, was known for its marble quarries and its talented sculptors and maybe the elaborate table support portraying Orpheus shown above was manufactured there; also mosaics maybe were made in one place and shipped to another; this could have been easily done for the small life scenes or portraits (emblemata) which often were inserted into a large mosaic decorated with geometric patterns; mosaics with small medallions portraying the Four Seasons have been found in many locations (e.g. the Mosaic of the Four Seasons from Ostia at S. Paolo alle Tre Fontane in Rome).

Museum of Sabratha: Mosaic portraying Liber Pater, a local god, as Dionysus and a detail of the decoration which surrounds the main scene (see the same subject in a large mosaic in Tunisia)

Return to page one to see the Forum or move to:

Introductory page

Oea (Tripoli)

Leptis Magna